Searching for Answers to Everest’s Greatest Mystery Among the Artifacts of Its Early Climbers

Mark Synnott on George Mallory, Sandy Irvine, and a Very Flimsy Rope

I found my way to the Foyle Reading Room at the Royal Geographical Society, where I was greeted by Jan Turner, a chipper fiftysomething librarian in a purple down vest. When I walked through the door, she was reading a membership ledger that had 1880 written on its cover. Turner handed me an application.

“Depending on how long you’re going to be here, perhaps it might make sense to join the society,” she said. The society has Fellows—she didn’t know how many—who vote and go to annual meetings and such. To become a Fellow, one must do “important work in the field of geography or exploration” and be recommended by at least two current Fellows. But there are also about 14,000 non-voting members whose ranks she was inviting me to join.

Turner said that many of the original Fellows of the society, which was founded in 1830, were naval and military officers who explored and surveyed in their spare time while posted in far-flung corners of the British Empire. The RGS has never been an academic institution per se, but it was directly responsible, through its long history of sponsoring exploratory expeditions and geographical research, for filling in many of the remaining blanks on the map. (Of course, Western “exploration” of the world often came at considerable cost to local populations in Africa, Australia, and many other parts of the British Empire.) Today, the mission of the RGS is to advance our collective knowledge of world geography and to support geographers across the world. The headquarters also serves as a repository for the society’s Special Collection, which includes 250,000 books, a million maps, and countless photos, diaries, letters, and artifacts.

When I told Turner what I was looking for, she handed me a thick, spiral-bound notebook with a sticker on its spine that read:

Archives

Special Collection

Everest Expeditions

1920s, 1930s, 1950s

Page after page, the notebook listed the items in the Everest special collection. I found my way to the 1924 expedition and made my own inventory of half a dozen boxes of photos, various correspondence of the Mount Everest Committee, and all the artifacts recovered following the discovery of Mallory’s body in 1999. As directed, I handed my list to another librarian, an older, gray-haired man named David McNeil who was standing at a large table studying maps of Liberia. He seemed slightly annoyed when I handed him the list, but he took it and headed out a door in the back of the room.

While I waited, I took a closer look around. The room was U-shaped and dominated by a bank of outward-tilting windows, which made me feel like I was standing on the bridge of a ship. Below the windshield on a long shelf sat busts of famous explorers and geographers, including David Livingstone, Richard Burton, Claudius Ptolemaeus, Gertrude Bell, and Ernest Shackleton. On the wall hung a magnificent black-and-white photograph of Makalu, the world’s fifth-tallest mountain. In its corner, written in pencil, was a photo credit—George Mallory.

McNeil soon reappeared pushing a wheeled cart covered in gray paperboard boxes. One by one he placed them on the metal table in front of me, then pulled out a pair of white cotton gloves. He slipped them on, opened the lid of the biggest box and ceremoniously lifted out what may be the world’s most famous boot.

“Wow, is that Mallory’s?”

McNeil nodded.

“Can I hold it?”

McNeil peered at me over his glasses, as if to say, Why do you think I’m wearing these special gloves? But said nothing.

I shook my head, marveling at the idea that anyone would have tried to climb the highest mountain on Earth in this boot. It was leather, and apart from a thick layer of felt sandwiched between the sole and the upper, it appeared to have no insulation. In fact, it looked almost identical to a pair of Dachstein hiking boots I wore on summer jaunts in the Adirondack and White Mountains. The toe was curled slightly upward and the sole rimmed with special V-shaped “boot nails” hammered into the leather to give traction on snow and ice. The side of the boot had a green, copper-colored tint, which I thought might be mold. “That’s chromium metal,” said McNeil, who had noticed me studying it. “They used it back in those days as a leather preservative.” I wondered if Mallory had applied it himself after he purchased the boots. The stuff must work well, because apart from a scuff mark on the inside of the toe, the leather was in remarkably good condition.

I shook my head, marveling at the idea that anyone would have tried to climb the highest mountain on Earth in this boot.

What struck me most, though, was that it looked to be my size. I wanted to slip it on and see how it felt. Then, of course, I pictured McNeil chasing me in his white gloves as I clodhopped across the room, the nails clippity-clopping on the floor. We moved on to another box. McNeil removed more items, including a leather sheath that once covered the pick of Mallory’s ice axe, a bone-handled pocketknife, and a plexiglass case containing a round-faced watch rimmed with tiny dimples. This, I realized, was the watch found in Mallory’s pocket in 1999. There were rust marks on the face where the hour and minute hands used to lie. Everest historians have debated these markings ad nauseum, but I don’t think most of them know that Thom, the climber who found the watch, took a photo of the watch before the hour hand fell off. I had seen the image, which showed clearly that the time was around 1:25—but a.m. or p.m., no one could know. McNeil explained that the watch had to remain in the case because it was radioactive. The face was coated in radioluminescent paint containing radium-226. McNeil said that if we turned the lights off, the watch would still glow a milky green.

There was one last box of artifacts, but McNeil wasn’t authorized to show it to me. He passed me off to another guy with a beard, who didn’t give his name but identified himself as “the conservator.”

“There’s nothing too interesting in here,” he said, putting his hand on top of the box where Handle with Care was written in bold type. “Why don’t we skip this one.” His reticence only made me more keen to see what was inside.

I played my best role as a pushy American climber, and after a few minutes, the conservator donned his own pair of special white gloves. Clearly annoyed, he daintily peeled back layers of tissue paper before lifting out some random bits of string and a clothing label that read W. F. Paine 72 High Street Godalming, and beneath, in small red letters, G. Mallory. Next came a pair of heavily rusted nail scissors, and then in the bottom of the box, a short length of thin white rope.

“This was tied to George Mallory when they found him,” he said solemnly. “It’s very delicate.”

Indeed, I could see tiny white flecks flaking off the rope as he laid it on the table in front of me. Now I understood why he had been reluctant to show it to me: The rope was disintegrating before our eyes. It was about as thick around as a pencil and comprised of three braided strands with a red thread woven inside, which I could only presume was a wear marker. Jochen Hemmleb, climber and mountaineering historian, had told me that the rope was made of flax and was originally 100 feet long. (After his 2010 Irvine search expedition, Hemmleb had a rope company create a replica and test its tensile strength, with appalling results.)

I simply couldn’t imagine using something this flimsy, even brand-new, to climb anything—let alone, technical rock above 8,000 meters on Mount Everest.

*

Three and a half days later, I staggered out of the RGS with a pile of notes and a mild headache. Jumping on the Tube, I headed across London to the headquarters of the Alpine Club. I knew I had found it when I saw what looked like a storefront with a bank of picture windows covered in bracing photos of mountaineers on high peaks.

I had called ahead, but I still caught the librarian, Nigel Buckley, in the middle of his lunch. “So what can I help you with?” he asked. I told him I was visiting from the States and had long been a fan of the club. I was doing some historical research on the early Everest expeditions and had heard that it had some Everest artifacts, including Sandy Irvine’s ice axe. I had seen a photo of the tool online, hanging up on the wall in a glass case. “Well, you’ve caught me at a good time,” said Buckley. “Let’s have a look around and see what we can find.”

Our first stop was the lecture hall. “Check this out,” he said, leading me to an old oxygen cylinder hanging from a wooden stand.

“This is one of the original 1924 oxygen bottles. We signal the start of every lecture like this.” Buckley took a wooden mallet and struck the metal cylinder. The sound that reverberated through the room reminded me of a Tibetan singing bowl. When it was quiet again, I told him about the hands-off policy at the Royal Geographical Society.

“Sometimes I’m a little embarrassed at how lax we are here,” he said, “but that’s why we have this stuff, so our people can enjoy it.” As Buckley looked on, I stroked the oxygen cylinder. Just because I could.

“Who sleeps down here?” I asked as we entered a bunk room in the basement of the building.

“Whoever,” replied Buckley. “You could if you want.” As I contemplated whether I could get out of my hotel reservation, Buckley disappeared into what looked like a storeroom and emerged two minutes later holding an ancient-looking ice axe. Then, without ceremony or even a hint of squeamishness, he handed it to me. Just like that, and without any white gloves, I was holding the ice axe that Sandy Irvine had carried on June 8, 1924. The axe was heavy, maybe five pounds or so, and about three-and-a-half feet long. The wood was dark and grainy and speckled with cuts and nicks. I could feel the vertical striations under my hand where the high-altitude ultraviolet rays had eaten away the wood along its annular rings during the nine years it sat out on the Northeast Ridge. The head of the axe was tarnished, but I could still make out the maker’s mark: willisch of taesch.

I simply couldn’t imagine using something this flimsy, even brand-new, to climb anything—let alone, technical rock above 8,000 meters on Mount Everest.

Buckley pointed to a spot on the shaft where three nicks, each spaced about a centimeter apart, had been deeply carved into the wood. “Those hatch marks are how they eventually figured out it was Sandy’s axe,” said Buckley. Lower on the shaft, about eight inches above the metal spike on the end, Buckley pointed out another nick.

“We think he carved this one to remind himself where to hold the axe when he was swinging it.”

I spent the rest of the afternoon in the Alpine Club’s library, rooting around in its archives, where I eventually found the personal papers of Noel Odell.

As the last person to see Mallory and Irvine alive, Odell’s name is inextricably linked with Everest’s greatest mystery. However, there is little in the written record about his long and varied life as a geologist, climber, and explorer.

Odell’s papers were organized into folders by year. The first folder I opened was full of letters concerning the ice axe I had just held. Percy Wyn-Harris brought the tool back to London in 1933, and it found a home at the Alpine Club, where it has resided ever since. Odell examined it shortly afterward, and according to his notes, he was the first to notice the three hatch marks. At the time, no one knew if the tool belonged to Mallory or Irvine. Odell, a mentor for young Sandy, was determined to find out. He wrote to both Ruth Mallory and Willie Irvine, Sandy’s father, in February of 1934. The originals of their replies were in the folder. On a piece of yellowed stationery that read westbrook, godalming in red type across the top, Ruth wrote: “As far as I know, George never marked his things with three lines”—here she drew the three horizontal lines one over the other—“or with any other mark. So I should think it very probable that the axe was Irvine’s.”

Willie Irvine apologized for taking so long to respond (ten days), explaining that the delay was because he had been investigating the matter. “Both Hugh and Evelyn think that Sandy used the triple nick III, but they are not certain. I, too, have a feeling that it is familiar—on the other hand, this may simply be an example of ‘suggestion’!” Willie goes on to say that he had searched through Sandy’s things, including his skis, the ice axe he used on an expedition to Spitsbergen, and his dairies, but could find no example of the marking. He said that his son generally used a monogram, which he drew on the page. It was clear from his letter that Willie was keenly interested in determining if the axe was indeed his son’s.

_____________________________________________________

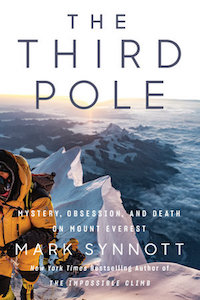

Excerpted from The Third Pole: Mystery, Obsession, and Death on Mount Everest with permission from Dutton Books. Copyright © 2021 Mark Synnott.

Mark Synnott

Mark Synnott is a twenty-five-year member of the North Face Global Athlete Team, an internationally certified mountain guide and a trainer for the Pararescuemen of the United States Air Force. A frequent contributor to National Geographic magazine, he is the author of The Impossible Climb and The Third Pole. He lives in the Mt. Washington Valley of New Hampshire.