Screensharing: Documenting Our

Long Year on Zoom

Brandon Taylor on Thomas Dworzak’s Digital Record of The Longest Year: 2020+

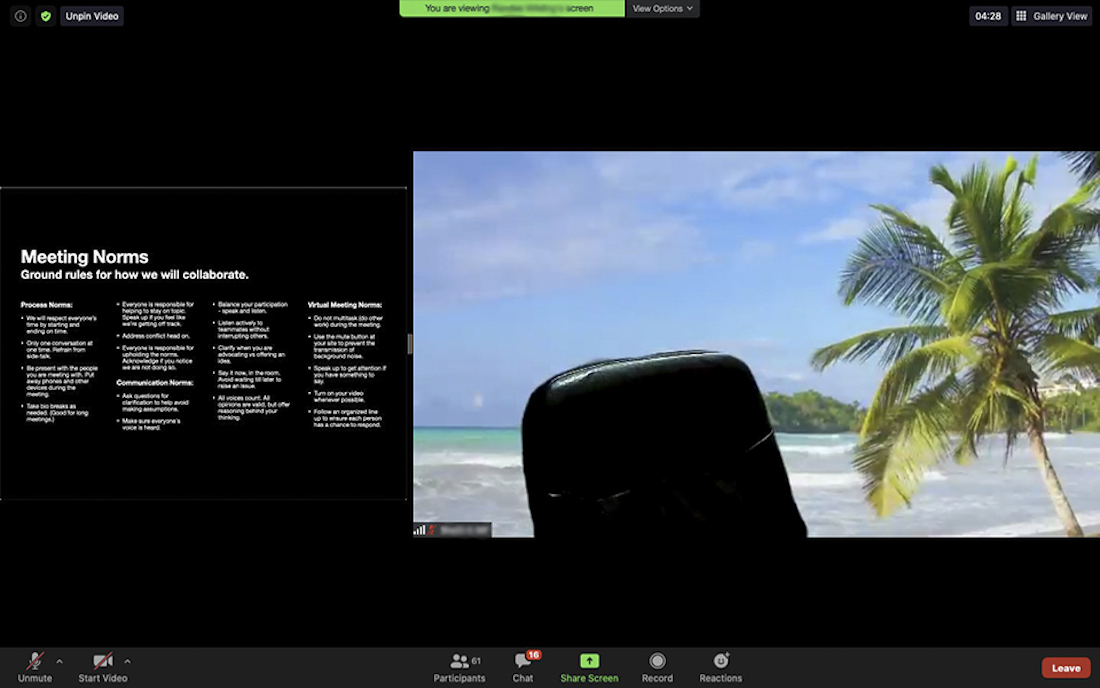

The Longest Year: 2020+ is a collection of visual and written essays on 2020, a pivotal year that shifted our way of experiencing the world. In most publications, images work in service to words—here they work in tandem. // In the second in the series Brandon Taylor considers photographer Thomas Dworzak’s documentation of this long year in our lives on Zoom. Since early on in the coronavirus pandemic Dworzak has attended hundreds of virtual events, several per day, all over the world, while sitting in his apartment in Paris: parties, intimate get-togethers, election rallies, vigils, community discussions, funerals, graduations, weddings, holidays, classrooms, and courtrooms.

I recently appeared in conversation with a friend for his digital book launch. I had assumed that we would be using the webinar format, but when the host admitted people from the waiting room, I could see their blinking, startled faces. It reminded me of a documentary I watched about orcas hunting, the way they herd confused shoals of fish to the strobing surface and then stun them with their tails.

I found it a little overwhelming, dizzying even, to be seeing so many faces, the low crackle of so many voices, all at once. It gave me that feeling I sometimes get when I watch TV or read books set in the before time, and the characters are eating in restaurants and touching each other’s faces. A near vertiginous sense of forgetting and then remembering almost in the same instant the danger of other people in such proximity.

Thomas Dworzak’s series is alive to the taut contradictions that striate our moment. If the television and film turned us into a culture of voyeurs, and social media turned us into a culture of personae, then Zoom has brought some of the sincerity back to our performances. There is something flattening to the democratic aesthetic of a zoom call in which hundreds of people participate. One can scroll through the gallery of participants and audience members, looking into their homes and their faces. Watching as their responses shift and morph in real time or in response to their internet connections. If the webinar recreates the typical hierarchy and preserves the social order, then the broad, flattening democracy of the many-peopled Zoom call is the Whitmanic restoration of some utopian ideal.

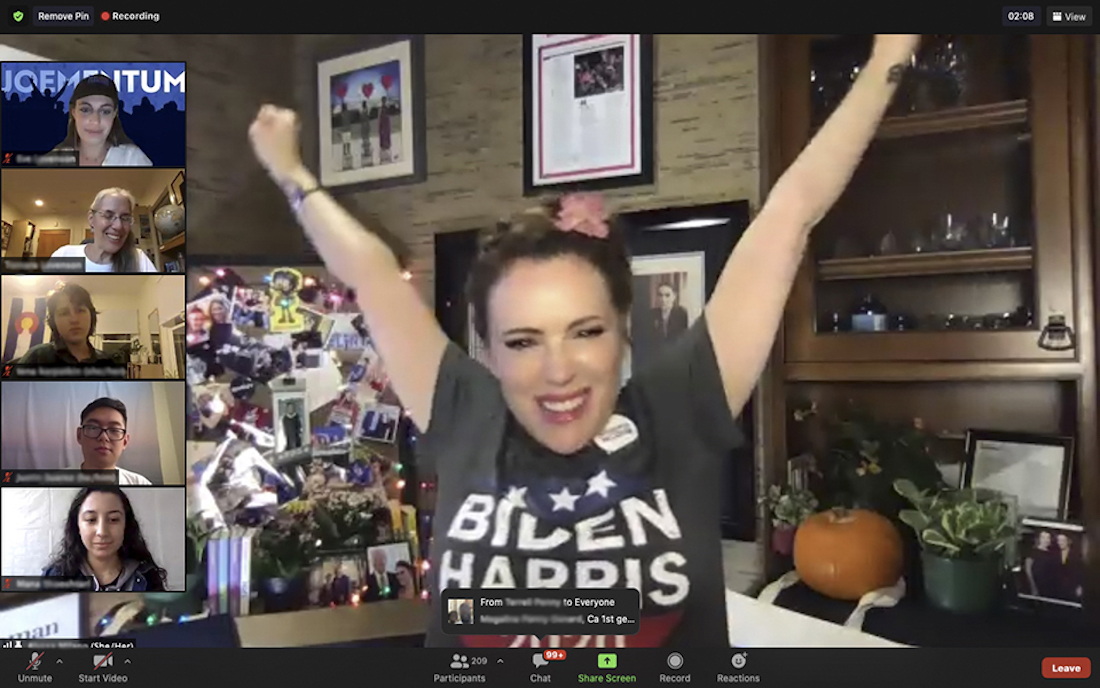

November 3, 2020. Actress and activist Alyssa Milano talks to Biden supporters in an event organized by the Biden-Harris campaign.

November 3, 2020. Actress and activist Alyssa Milano talks to Biden supporters in an event organized by the Biden-Harris campaign.

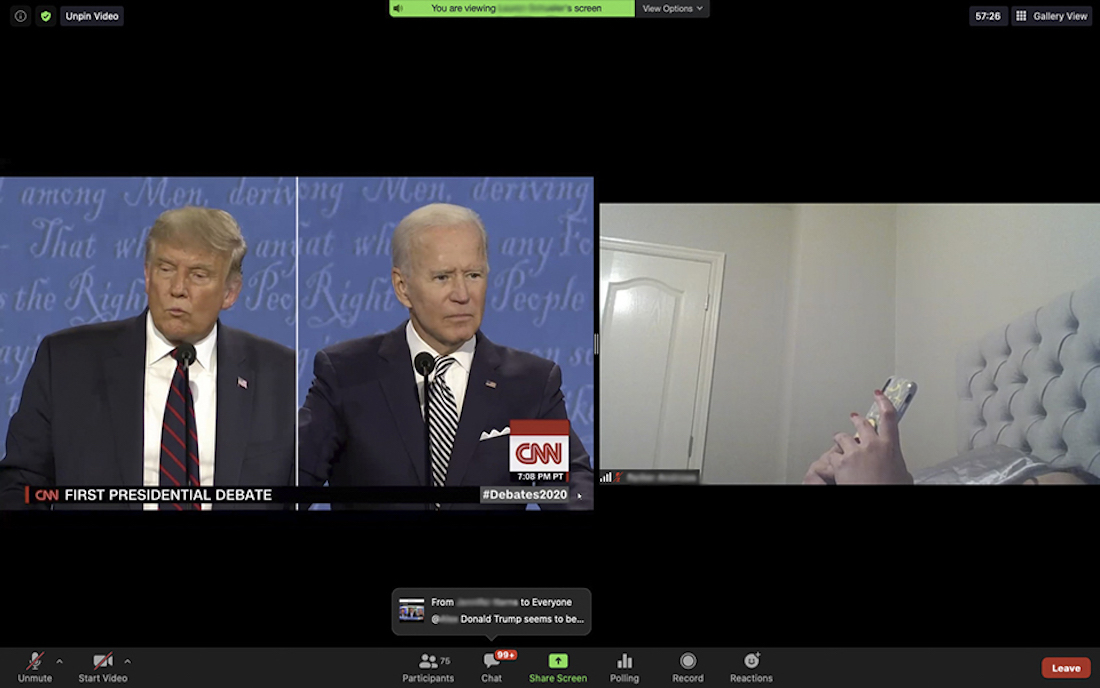

September 29, 2020. Trump-Biden Debate Watch event on Zoom.

September 29, 2020. Trump-Biden Debate Watch event on Zoom.

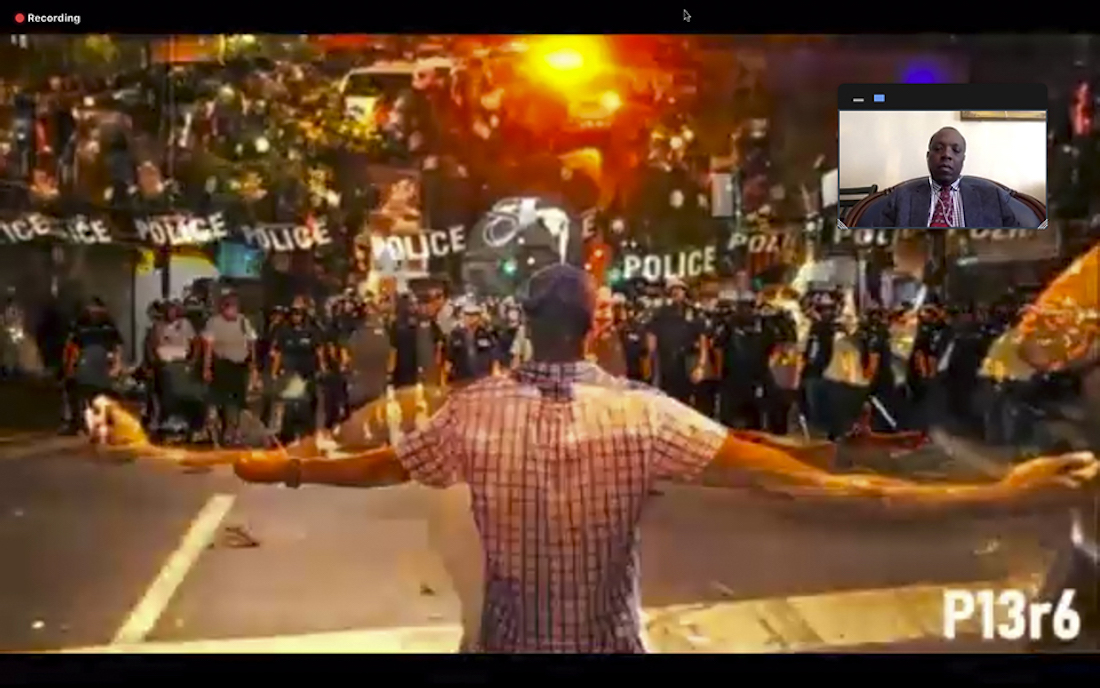

June 8, 2020. Pubic virtual vigil, attended by more than 300 people on Zoom, in Hackney, England for Black Lives Matter, in solidarity with George Floyd’s family.

June 8, 2020. Pubic virtual vigil, attended by more than 300 people on Zoom, in Hackney, England for Black Lives Matter, in solidarity with George Floyd’s family.

May 31, 2020. George Floyd Remembrance Vigil and Community Discussion virtual event on Zoom to honor George Floyd, Eau Claire, Wisconsin.

May 31, 2020. George Floyd Remembrance Vigil and Community Discussion virtual event on Zoom to honor George Floyd, Eau Claire, Wisconsin.

Dworzak’s work is playful in the way it captures the banal chaos of children attending remote school, each of their faces a different kind of perplexed boredom. It reminded me of being in school, the way my attention was drawn to my classmates faces and to their desks rather than toward the front of the room. That diffusion of attention, much feared and bemoaned, was, in the context of growing up and attending class, the very point of school to me and to many others. School wasn’t about the facts beamed into our brains from our instructors. It was about what your friends were hiding in their desks or what they were drawing while the teacher went over fractions. One sees in the portraits of remote learning some of that old, familiar shiftiness. That part of school that makes a mind porous to everything but what you’re supposed to be learning.

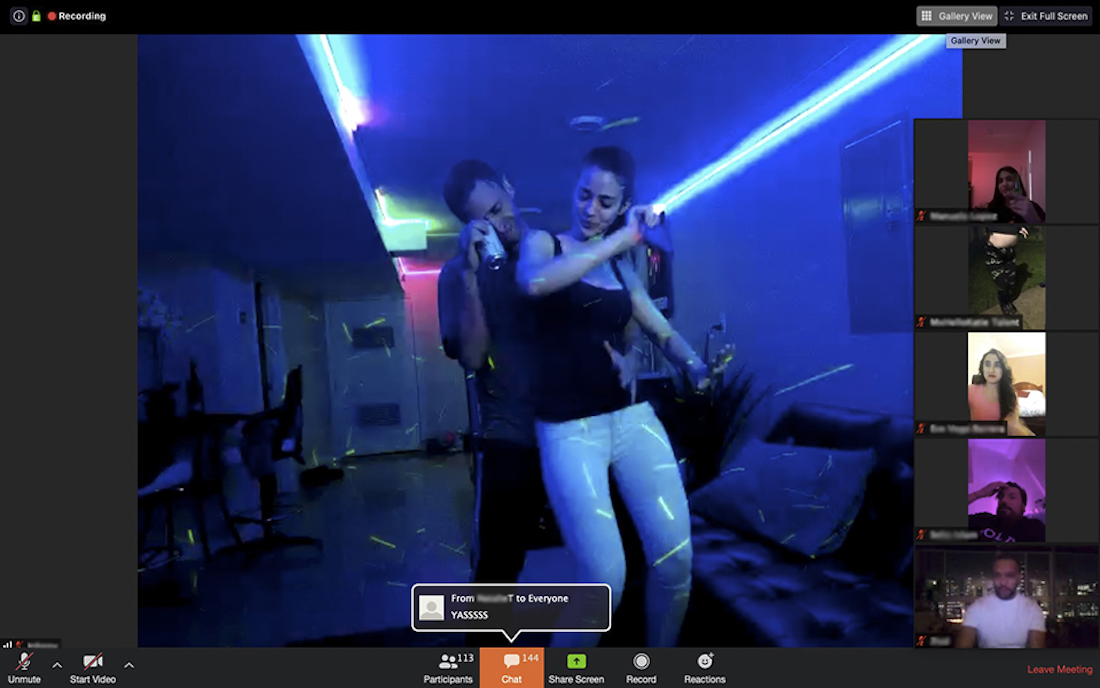

Dworzak also captures some of the postmodern collage effect of Zoom. What else to call a dance party or debate watch party over Zoom. Everyone consuming the same media, but also becoming a part of the media that is being consumed. This was never more clear than in the images taken during the public vigils for Black Lives Matter and for George Floyd. There was something beautiful about people from all over the world coming together and making their faces visible and present to the affirmation of Black lives, and bearing witness to the extinction of one of those lives, George Floyd. There is something potent and glorious about that. People in their coats and on their sofas, people tuning in via Facebook livestream. I don’t know. Zoom comes to feel like one of those improvised memorials you find on the sides of buildings or beside roads or at crosswalks. The confluence of disparate mourning gathered up in one place, usually the site of the violence and loss.

May 2020. Facebook live funeral. USA.

May 2020. Facebook live funeral. USA.

April 21, 2020. Children attend Zoom school in Tbilisi, Georgia. (Also below.)

April 21, 2020. Children attend Zoom school in Tbilisi, Georgia. (Also below.)

May 17, 2020. The Avalon Ball, Los Angeles, California, hosted by the Art Deco Society of Los Angeles; held on Zoom.

May 17, 2020. The Avalon Ball, Los Angeles, California, hosted by the Art Deco Society of Los Angeles; held on Zoom.

April 25, 2020. Lisette Oropesa performs at the virtual Met Gala Live. Livestream (not Zoom).

April 25, 2020. Lisette Oropesa performs at the virtual Met Gala Live. Livestream (not Zoom).

There’s a part of me that still feels Zoom is too informal, too new a medium to portray the solemnity of an occasion. Part of that, I know, comes from the fact that Zoom distorts hierarchy of authority and power. It also has to do with the fact that Zoom gets in around the curated self. It opens a portal into our homes, where we are most exposed, most ourselves. On Zoom, we try to perform as we normally do, partaking as voyeurs in the culture, but suddenly, the one-way mirror is two-ways. We are watched even as we watch. And we become part of the performance. We become stiff and anxious about disrupting the flow of the event. Drawing attention to ourselves by accident. We are no longer able to partake in quiet anonymity.

That’s the part of Dworzak’s work I enjoyed the most. The way he captures the idle moment. The unperformed expression in response to other people as we try to remake this world in the digital space, finding what translates and discarding what doesn’t. He preserves the strange tension of trying to carry out this life online, and reveals perhaps the most surprising truth yet: that in this digital age of constant self-surveillance and self-promotion, the most startling thing of all is still glimpsing another person.

April 25, 2020. Public dance party on Zoom.

April 25, 2020. Public dance party on Zoom.

May 16, 2020. Public party on Zoom.

May 16, 2020. Public party on Zoom.

Robin di Angelo reading on Zoom.

Robin di Angelo reading on Zoom.

June 20, 2020. Virtual memorial for Martha Hine held on Zoom.

June 20, 2020. Virtual memorial for Martha Hine held on Zoom.

_______________________________

The Longest Year: 2020+ is a collection of visual and written essays on 2020, a pivotal year that shifted our way of experiencing the world. Edited by Rachel Cobb, Alice Gabriner, and Elizabeth Krist.

Rachel Cobb is a photographer who lives in New York City. She has worked for numerous publications including The New York Times, TIME and Rolling Stone magazine. Her award-winning book Mistral: The Legendary Wind of Provence was published by Damiani in 2018. More of her work can be found here.

Alice Gabriner is a visual editor, instructor and mentor with 30 years of experience at publications, including The New Yorker, The New York Times, National Geographic, and TIME. For the first two years of the Obama administration, she served as Deputy Director of Photography.

A National Geographic photo editor for over 20 years, Elizabeth Krist is on the boards of Women Photograph and of the W. Eugene Smith Fund, helps program National Geographic’s Storytellers Summit, and advises the Eddie Adams Workshop. She curated A Mother’s Eye for Photoville and CatchLight, and the Women of Vision exhibition and book.

Brandon Taylor and Thomas Dworzak

Brandon Taylor is the author of the novel Real Life, which was a New York Times Editors’ Choice. His work has appeared in Guernica, American Short Fiction, Gulf Coast, Buzzfeed Reader, O: The Oprah Magazine, Gay Mag, The New Yorker online, The Literary Review, and elsewhere. He is a staff writer at Lit Hub. He holds graduate degrees from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he was an Iowa Arts Fellow.

Thomas Dworzak has produced a number of books and is a member of Magnum Photos. He was elected President of Magnum in 2017. Dworzak won a World Press Photo award in 2001 and in 2018 received an Honorary Fellowship of the Royal Photographic Society.