Scholastic recognizes 100 years of teen writing.

What do Amanda Gorman, Truman Capote, John Updike, and Joyce Carol Oates have in common? Each won a Scholastic Art & Writing Award as a teen.

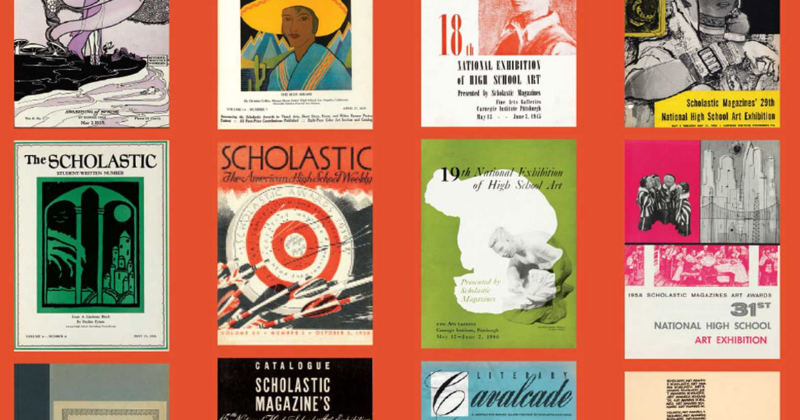

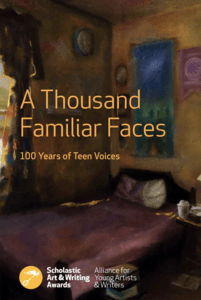

The Scholastic Art & Writing Awards began in 1923 and continue to support young writers thanks to The Alliance for Young Artists & Writers. This marking a century of work, Scholastic has published an anthology of carefully selected works from winners across different eras: A Thousand Familiar Faces: 100 Years of Teen Voices.

Hannah Jones won an award as a high school senior in 2004, went on to become a fantasy author, and co-writes novels with her wife. Jones worked as editor for the 100-year project, which she describes as a “call across time,” and spoke with Literary Hub about what the project means, what teen voices across different eras have to say, and what we can see in the juvenilia of famous writers.

Lit Hub: All these incredible people have been involved with the award over the last century. Are there any writers who’ve come through the program in a different time that you really connect with?

Hannah Jones: There are so many really, there are some that went on to become very famous, like one of my favorite writers in any genre, Samuel Delany. I found one of his works in the archive, a prose piece about grief, not science fiction or fantasy, and that was just so electrifying to come across.

In the book there is a piece by Bernard Malamud from from back in the day called “Life From Behind the Counter” about his teenage job working at a department store, and you come across that and think, wait, what?! [This is] some of the earliest writing of these people who go on to be these great names in American canon.

But for me too, some of the most exciting stuff is to read a piece and I look them up and I try to find them and and they probably never went on to write more, but their work is preserved as a part of the American story. It’s so exciting to be able to read some of them for the first time in 60, 70, 80 years.

LH: Historical events are one way to look at curating the archive, but were there other themes that stood out to you across time, or other ways to understand the collection?

HJ: Yeah, it’s organized by theme as opposed to by year because there were things that really resonated throughout time, but there are certain things that don’t necessarily speak to a specific theme, like hair. [Teens are] always writing about hair and how important it is to us and our identity. Also grief and the way that younger people process grief.

And because I love fantasy and genre fiction so much, I loved to watch the evolution of fantasy and science fiction right across the years. What that looks like in the twenties is so different from what it starts to look like in the sixties.

LH: What kind of an evolution did you notice?

HJ: A lot of the pieces from the earlier works like in the twenties and thirties I noticed were stories carried over from grandparents from an old country. It was very ancestral and from somewhere else, but it’s brought to America and then it, once you hit the sixties really, it’s very much responding to scientific advancements and atomic and nuclear power and dealing with that in surprising ways.

There’s a poem in there that I love so much that’s about a test rat who goes up into space and it’s the rat sort of speaking to his family back on Earth.

And then there’s a piece from the twenties that’s about a firefly who’s been kidnapped by a child and he’s writing to his family trying to get back to them. So it’s just how every child is trying to relate to the world around them and telling these stories of—I think the line—is “I am a missable creature,” and I just love that.

Do you have any thoughts as an editor about how as a reader you can relate more to age than you do specifically to era?

That’s such a good question. There’s a piece that didn’t make it into the anthology because very long it was a dramatic script called “The Teenage Age,” and in it kids are talking about boys and about friend groups that they don’t fit into and it’s from the early, early eighties and they’re talking about, Oh, there’s this girl on a commercial and I don’t look like her.

And there’s a piece from I think the thirties called “High School Is a Disappointment,” about how this girl thought she was going to go to high school and it was going to be a total change from schooling of the past. She was going to really open her eyes to the world of adulthood and she realized it’s just school still, and that’s something everyone can relate to.

So I think it’s that element of flux and trying to discover yourself and learn yourself and know yourself and reach out to someone else in that particular age that [makes it so] experimental and raw, and that’s why I think you can relate to it so much. There are pretenses because of course there are, but it’s so much truer to the bone.

You mentioned this idea that especially for genre writers, their early work might not have been as formed into that kind of shape that it later attained. Do you have any thoughts on how as readers or as writers even, we lose the ability to tap into a mindset, and maybe as a society treat work by young writers and young artists differently?

Absolutely, and that’s something that you see in a lot of the teens as they grapple with: Is my voice even important? Does anyone want to listen to this? Does this even matter?

That calling out for me has always been really important because [in this project] there’s an answer; it makes the act of creativity a little bit less lonely. This feels like a call and an answer across time. I don’t like anything else like this exists, a record of a specific age group across a century.

There’s a piece by another famous genre writer Peter Beagle who wrote The Last Unicorn in here—he won for a poem about Abraham Lincoln. And I do think, you know, there is, there’s a lot of, a lot of times there are people who are like, you have to write a certain way, you have to follow a certain formula, you know, study these particular writers and write like them.

For me as as a young person when I was writing, it’s very lonely and daunting and again, you have that sense of who wants to hear me? and having some stranger read that work and say I care, this was good—really it cannot be overstated how much that can mean to like someone who’s just creating alone in the dark.

It’s funny how that is true no matter how well published you are.

Exactly.

Do you have a sense of who your audience is for your fantasy books?

I hope it’s outcast people looking for found family. I never really saw myself in a lot of the fantasy books that I read as a queer person. So I’m very excited to see so much more of that now and to be a part of that.

I’ve edited a couple of best teen-writing anthologies for the classic Art and Writing Awards before, which is just an anthology of the year, the year, that one year competition—which, you may not be surprised to hear, it’s just as hard to select from just one year as it is from 100 years somehow.

But it’s just so exciting to think about being able to give that queer kid in Kentucky who’s writing about this queer experience the opportunity to have that on a page and then someone else reads it and reaches out to them. It’s very important.

What was it like going through the archive to find this work?

It was a very large undertaking because it’s 100 years of the publications, and they existed in a lot of cases just as hard copies in the library and in the archives at the Scholastic building.

[The archive team, including Deimosa Webber-Bey, Director of Information Services & Cultural Insight at Scholastic, Chelsea Fritz, Associate Librarian at Scholastic, and Henry Trinder, a research intern] worked for months just going through and scanning just all of these old publications from the 1920s up until literally last year. And [Henry was] just making sure that it was digitized as a PDF, narrowing that down to … 400, 500 works that he thought sort of really spoke to moments in time or really seem to sing.

The Saplings collection, which just publishes really all of the writing award-winning works from the teenagers throughout those years, is such a stupendous archive of kids reacting to the most impressive and incredible and unbelievable historical events around them. And then I think about how in 100 years, someone’s going to be doing the same thing for the kids who are reacting to these unprecedented, unmanageable, unbearable events right now.

My great hope is to make it accessible to the public so that people can just browse them and discover someone and then chase their story, look them up and try and find out more information about them, like I kept doing with various writers throughout this process.

What do you tell people about why you think they should read this project?

You will discover a new favorite writer who no one has ever heard of. And it will take you on a journey to learn some part of America’s larger story that you would not have otherwise known.

I feel so enriched by this experience because I would chase down certain individuals and be like, what did this person go on to do? There’s one man who wrote a beautiful nature poem, and now he’s a journalist who writes about the environment.

A Thousand Familiar Faces: 100 Years of Teen Voices is available to the public here.