Scenes from an Emergency Clinic in the Sonoran Desert

On Death in the Borderlands and Who is Allowed to Grieve

There are three shrines in a mountain saddle in the Altar Valley. The saddle looks like a half-moon, as if someone from above took a bite out of the middle of the gargantuan peak. In this crux, there is the shade of Mexican blue oaks and spindly, stunted-looking junipers, full of fragrant, inedible berries. Shade in this desert is sparse. Under these trees are piles of trash, sun-bleached plastic water gallons degrading into splinters along with cans, once full of beans or tuna, now empty, turning to rust. There are backpacks, torn sweaters, and handmade shoe covers that leave no footprint in the sandy washes—the dry stream and riverbeds of the Sonoran Desert. There are toothbrushes, makeup kits, and other personal items discarded off the main trail. The trail winds up the mountainside from the south, from south of the border between Nogales and Sasabe, and heads north to a network of other paths carved into the desert, which if followed correctly, lead past Border Patrol checkpoints into the interior of the United States.

One shrine is for La Virgen de Guadalupe, another is dedicated to the Patron Saint of Migrants Santo Toribio, and the third to Santisima Muerte—the Saint of Death. In little crevices around these shrines are prayers written on scraps of paper; there are crucifixes, rosaries, and broken glass candles. All the components of these shrines came from Mexico and were important enough items for someone to carry as they walked for days through the inhospitable terrain.

Next to these shrines there is water. Some of it is a little green tinted, dredged up out of a cattle tank, put in thick black plastic jugs, carried here by migrants, and left as an offering to the saints or small gift for other travelers who were not lucky enough to have passed the tank. The water is murky and teeming with bacteria, but it’s lifesaving all the same.

We too leave water. But we walked from the north heading south, and this shrine is our destination, not a stopping point. The water we leave is in clear plastic jugs with blue lids, and is pure and bacteria free. I scribble with a Sharpie aqua pura para migrantes and suerte on the sides of a gallon. The desert landscape is littered with thousands of black jugs carried from the south and clear gallons graffitied with well wishes brought from the north.

*

People walk between three days and several weeks in order to pass through the borderlands—that land north of Border Patrol checkpoints considered the interior of the United States. The place we call Triple Shrine, in the saddle of Bartolo Mountain, lies at the heart of this journey. Triple Shrine is half a day’s walk south of our camp, an off-the-grid first aid clinic tucked away on a dirt road outside Arivaca, Arizona. The camp sits about 12 miles as the crow flies from the US–Mexican border. Over the years at this camp and in the surrounding desert, I have gotten to know hundreds of people from Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Belize, and Ecuador as well as people who grew up in the United States and consider it home yet have birth certificates from the nations to which they were deported. As we provide care for those lost and injured in the desert, they often share their complex stories of where they come from and why they are walking through the Sonoran Desert. The camp has served as a place of respite for a myriad of people over the past decade, and despite some similarities in the stories of those coming to seek asylum or as economic refugees, there is no archetypal migrant found here.

My head is full of stories shared with me in the desert. I try to recall details, but so often the faces of the people whose stories have forever changed me seem to have faded from my mind. In my time at the clinic I’ve met children, mothers, and fathers as well as people five years younger than me yet aged decades beyond their years. Walking through the desert is the cheapest and most dangerous way to cross into the United States without papers, and so frequently the people we meet are poor, but sometimes they are middle class. There are urbanites, and people who have never left their mountain village before this journey; people who are distrustful of me; and people who I now call friends. I’ve met indigenous Guatemalans whose Spanish is as shaky as mine, and people whose first language is English.

“As we provide care for those lost and injured in the desert, they often share their complex stories of where they come from and why they are walking through the Sonoran Desert.”

One of the first people I ever met in the desert turned out to be a US citizen. He spoke fractured English, although said he was from Nogales—a city split in two by a border wall. He had been visiting some friends in Sasabe when cartel members kidnapped and tortured him, and then forced him to carry supplies for a group of smugglers transporting burlap sacks of drugs on their backs. The group abandoned him in the desert after another cartel member picked up the smugglers and contraband. We let him use our phone so he could call his mother, who hadn’t heard from him for weeks. The Border Patrol agents and sheriffs were highly skeptical of his story, and treated him harshly, but ultimately he proved his status and filed a police report, and they dropped him back off at his home in the city.

At the clinic I met a man nicknamed Bigotes (in English, mustaches) who was deported from his home in the United States after he got entangled in a messy love affair, was shot by a jealous man, and went to a hospital to be treated for gunshot wounds. The hospital staff called immigration when he failed to produce legal documents. He told raucous stories while he healed from severe dehydration and a twisted knee.

Right before another man arrived at our clinic, bandits had captured him in the desert and told him they were going to torture him as they extorted his family. He narrowly escaped with his life; he ran away with shots ringing out behind him. This man, the father and grandfather of US citizens, was ripped from his life in Utah after a routine traffic stop and was fighting like hell to make it back to his family. Last I heard of him, he never made it home.

I also recall the Jamaican Guatemalan who hit on me while I was checking his blood pressure. He told me tus ojos son bonitos como los de mi abuelita (your eyes are beautiful like those of my little grandmother). I laughed it off, and later he told me that if he didn’t make it to his destination and if I ever visited Lago Atitlan in Guatemala, he would love to have me as a guest at his home near the lake. The idea that I could just hop a plane and land in his country as a tourist while he was walking through hell to enter mine was not lost on either of us.

I provided care for a developmentally disabled man of 50 who was fleeing cartel violence in Sinaloa, Mexico. His sister had made it to the interior of the United States, and he was coming to live with her. I left the clinic the same day he did, and the next day I attended the court proceedings that mass prosecute 70 individuals a day in Tucson with charges of illegal entry. The man was shackled in chains at the wrists and ankles. He didn’t see me sitting in the back until he pleaded guilty. He waved to me as he was led out of the courtroom by US marshals. I followed up with him during his six-month sentence in a for-profit prison that lies an hour north of my home in Tucson.

One of the strongest people I’ve ever met was a tiny 15-year-old girl journeying alone from El Salvador; she recounted how she rode La Bestia—the infamous and deadly freight train used by Central American migrants through Mexico. After months of traveling, she found herself abandoned by the cartel guide paid to get her into the United States, only to have a gun pointed at her head by a Border Patrol agent, who then left her in the midst of the desert without taking her into custody. The worst part, she told me as she taught me to make pupusas one night at the clinic, of the several days she spent alone in the vast desert was the howls of coyotes in the night; she thought they were wolves coming to eat her.

I think often of another woman, an upper-middle-class business owner from Mexico City who was crossing to reunite with her lover. She didn’t have family members or friends who had crossed, and didn’t know the state of afairs on the border. She didn’t know she would have to pay tenfold the initial cost of the journey to extortionists over the course of a torturous month or about the preposterously high rates of sexual assault of female travelers. She kept telling me, I’m like you. I volunteer to help people. I can’t believe this has happened to me. People need to know about this.

*

All over the nation, televised and in print, there are news articles describing the backstory of each of the five recreational hikers or mountain bikers who perished from the heat wave that struck Arizona in June 2016. Two of the dead were not citizens; they were tourists from Germany. The news describes the tragedy of lost life, of how easily one dies of dehydration or heatstroke even just a few miles from civilization. It reports on the search-and-rescue initiatives for these people who passed away in the mountains outside Tucson and Phoenix.

There is public grief, discussion in the city about how terrible this needless loss of life is, and sympathy for the family members of the five dead. I feel it too. I have hiked these trails that these people died on. I have had heatstroke, felt dizzy and nauseous; I have feared my body’s ability to withstand. As I read the reports, I ache for their families and think to myself, I could have been one of them; that could’ve been one of my friends.

But these headlines are inaccurate; the death toll is certainly far more than five. There are dozens, hundreds possibly, who perished in the borderlands during this heat wave. The majority of those who died are not US citizens, nor tourists with visas and German bank accounts.

I used to think the lack of news coverage of the death of people of color was negligence on part of the media, but it’s bigger than that; perhaps it’s cultural, systemic. Some death and injustice is expected, not shocking or newsworthy, because it’s been in the backdrop of our culture since the inception of the United States.

“In the United States, there are communities whose deaths and murders are justified because of the color of their skin, because of their criminalized existence.”

In November 2014, mass graves of undocumented immigrants were uncovered outside Falfurrias, Texas. Border Patrol agents had been finding corpses and skeletons of undocumented people in the brush of South Texas, and turning them over to a private funeral home. Rather than recording DNA and potentially providing closure to the families of the dead, or allowing for proper burial, the funeral home placed most of the bodies in trash bags and piled them into mass graves. These sites received some national media attention, but quickly and decisively a court in Texas ruled there was “no evidence” of wrongdoing in the case, although the funeral home collected tens of thousands of taxpayer dollars to gather DNA and properly bury the bodies. No one was charged, and there was no change of policy for how the remains of undocumented people are handled. There were never any numbers released concerning the amount of people dead in the mass grave, let alone names or stories about those who perished.

In the United States, there are communities whose deaths and murders are justified because of the color of their skin, because of their criminalized existence. One of those communities is the population crossing the border, the millions of undocumented people living “illegally” in the interior of the United States along with the tens of thousands of Mexican and Central American citizens locked up in detention centers and for-profit prisons. Their legal status in this country translates into easily justified deaths because they are committing the crime of crossing the border; death is justified as the penalty for this crime. The undocumented community that loses so many of its people to murder by border enforcement and policy in general cannot easily speak up; it is not given the same platform as citizens to publicly grieve its people or demand the attention of the outside world. According to official estimates, only half of those who die in the borderlands are ever recovered. The millions of undocumented people living in the United States are often silenced by their lack of rights, the fear of raids and deportation, the reality of the borderlands where people die and go unsearched for, where mass graves are considered legal even as the bodies within them are marked as illegal.

It’s not just the media or state policy that is to blame for this disparity in the value of life of a citizen versus that of a noncitizen, or a white person versus that of a black or brown person. Rampant xenophobia and racism in this country have crafted a culture where the death of migrants in the desert, or murder of people of color by police or the state, is inconsequential. I recall the words of the forest ranger who issued my permit at the Cabeza Prieta Wildlife Refuge when I was on a search and recovery for three dead humans. She said, You know you’re helping criminals, right? Scum of the earth. These aren’t mom-and-pop types coming to work anymore. No, scum of the earth, get what they deserve. State and corporate powers have conspired to funnel undocumented people into the deadliest parts of the borderlands, and the people who have traveled through these places or lost family to the desert and brush know what is happening in the borderlands regardless of the lack of media. In a world that frequently invalidates the humanity of those who perish in the borderlands, communities that have lost loved ones as well as communities in solidarity know that these people did not “get what they deserve” when they died from exposure, dehydration, and deadly Border Patrol tactics. There is grief and mourning, even if it is hidden from public view.

How many people died that week this past June on the border and will never be searched for? How many bodies will never be recovered? In two weeks in this climate, corpses become skeletons, and over time the skeletons become the dust of the desert. There may never be closure for the families of those who died. There are few newspaper reports that make readers feel the pain of loss, or think to themselves, That could’ve been me or someone I love. Because the truth of the matter is that for those of us who can pass through interior checkpoints, that couldn’t have been us: dead in the desert, unsearched for, never laid to rest by loved ones.

*

The border between the United States and Mexico has been the hardest thing I’ve ever tried to write about. It is more than a boundary on maps, more than a line drawn in the sand that separates nation-states. It is a 1,000-mile stretch that means countless things to millions of people, all with different backgrounds and different reasons for living, working, or migrating through. The border is a physical expanse that has consumed the lives of thousands over centuries; it is a modern-day glimpse of the bloody history of colonization and blatant racial division that the United States is founded on; it is a boundary that lives in the memories of those who have crossed it, those who have lived in it, even those who have simply heard about it in the news. There have been hundreds of books, histories, and poems written in attempts to make sense of this intangible realm where physical space, macroeconomics, and personal histories intertwine into crisis. The border is oceans and brush and desert. The border is Border Patrol checkpoints and drug-cartel territory and stolen native land. The border is a low-intensity war zone as well as home to many.

Ultimately the border is a land of polarity, a land of illegal and legal, a land of can-pass-through and cannot-pass-through checkpoints. There are people here, Border Patrol agents and militia, slashing full water gallons, but also there are people leaving the water they cannot spare so that others who need it just a little more than they do can survive. There are people hanging effigies of migrants in trees to serve as a warning, and there are others who risk the freedoms and privileges they were born into so as to help those in need. There are too many complicated players to truly make sense of this place, to make sense of all the death. Stories of death and hope inundate the community here—the community of locals in the borderlands, those of us from the city, and the hundreds of volunteers who come from all over to organize and provide mutual aid.

So often the work we do has no easy conclusion; we search for those we never find, and no matter how many thousands of gallons of water we put in the desert, still the rates of death due to exposure and dehydration steadily climb. Resistance in the borderlands can feel like an endless battle against the border militarization complex—a mechanized, murderous, and intangible enemy—and burnout isn’t a foreign concept. Frequently it feels as though the state, corporations, and media have successfully stripped the thousands of people crossing the border of their humanity.

Despite the border apparatus and xenophobic rhetoric designed to dehumanize, imprison, and kill, though, there are many communities comprised of hundreds of individuals working in solidarity with those crossing through the borderlands, listening to stories, providing aid, and organizing in a myriad of ways to rise up against the militarization of the borderlands. Seeing how the state strips people of their dignity and drives them into the deadliest parts of the desert brought my community together in the first place. Border work is predicated on ending the deaths of those crossing—currently an insurmountable task—and much of the action we take is in response to grief, but also anger and hope; the three are inseparable motivations that sustain organizing and action within our community.

When I leave the clinic and go back to the city, I try to spend a day or two self-isolating. I light candles for those I have met who are still traveling through the desert, and my heart feels heavy with worry for the future that awaits them. I try to sit with the chaos of never again seeing these people whose stories will perhaps forever haunt me, and I cannot fathom the grieving of the undocumented communities that have lost family members in the borderlands. I attempt to understand my place, my comfortable place, as a US citizen, floating between worlds, between the no-man’s land south of interior checkpoints and mundane urban existence.

Yet I do not hold this grief alone. When I need to rant or cry or scream, I seek out my friends—fellow solidarity workers who know exactly what it means to walk between these two worlds, to go from a world of drones and human hunting and scattered human remains into the city where none of the suffering from the hills just outside the city is heard. When there is seemingly no end to the sea of grief and death in the borderlands, it is the stories of survival that pull us together and keep us going. It is the moments when I hike deep into the desert wilderness with some of my closest friends and see green water carried by migrants left for others that help me make sense of this ugly world, that allow me a glimpse of a world where not everyone is out to destroy others.

“No matter how hard the state attempts to criminalize aid for others in need, it has failed at destroying solidarity.”

The work we do is in solidarity with those crossing the border and living without papers in the United States, but our grief is not necessarily in solidarity; our grief is our own. I grieve for the loss I feel when I part ways with someone in the desert, and the pain I feel because murderous policies permit mass graves and deport people I know. I grieve when I come across bones in the desert that turn out to be human, although my sorrow is inherently different than that of the family of the person I’ve found. I am just one in a community that walks between two disparate worlds, and frequently our only solace is in one another, in talking about the small victories, in speaking of the bizarre and hilarious colliding of cultures at our camp clinic. When things feel bleakest, we often collectively recall and share with others the stories of the people we have met who have survived despite a multibillion-dollar budget to track them down. Together we all mourn what the media and mainstream society refuse to acknowledge: the importance and complexity of the lives of those who travel through the borderlands. When the pain of interfacing with so much near-invisible suffering becomes too much, the only thing left to do is to walk south on the trails together, carrying as much water as we can to leave for those walking north.

Although we leave water in a thousand crevices throughout the Sonoran Desert, it is within the crux where there are shrines honoring La Virgen de Guadalupe, Santo Toribio, and Santisima Muerte where collective grieving and collective action visibly merge. Migrants themselves have crafted these shrines and carried with them symbols of hope to leave as a mark in the desert. No matter how hard the state attempts to dehumanize the untold numbers of people coming through this desert, it has failed at eradicating all their hope. No matter how hard the state attempts to criminalize aid for others in need, it has failed at destroying solidarity. In this land where water is life and the lack of it is death, a water bottle has become a symbol of resistance to the murderous policy of the state. Water, brought from both the north and south, is offered to those in need; it is also offered to the saints, so they’ll watch over the living and dead in this perilous desert.

We leave water by the three shrines, as our scrap of a message for safe journeys and, too often, plastic memorial stones for those who don’t make it.

__________________________________

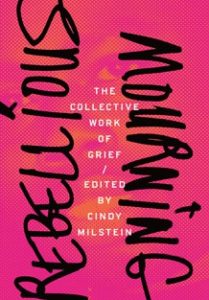

From Rebellious Mourning: The Collective Work of Grief, ed. Cindy Milstein. Used with permission of AK Press. Copyright © 2017 by Lee Sandusky.

Lee Sandusky

Lee Sandusky has spent the past four years living in Tucson and organizing on the ground with a grassroots, consensus-based organization called No More Deaths / No Mas Muertes—an umbrella organization for several separate working groups that each interface with migration differently; she has worked primarily with the search-and-rescue team and Desert Aid. Lee is currently working with a collective to compile and edit an anthology of creative pieces about how borders impact life in the Sonoran Desert. She’d like to thank all the people who are working visibly or invisibly to dismantle the systems of control that keep people from moving freely and apart from their communities, and in particular her fellow Desert Rats, who have poured innumerable drops of blood, sweat, and tears into the borderland.