Saving Nora: What It’s Like to Operate on a 500-Pound Polar Bear

Kale Williams on the Challenges and Risks of Animal Surgery

Jeff Watkins had spent more than 30 years, essentially his whole career, fixing fractures in large animals, but the email he got in late January still caught him by surprise.

Watkins had studied veterinary medicine in Kansas before going to grad school at Texas A&M, where he became fascinated with the anatomy of horses—the interplay of muscle and bone, how joints rotate and support the mass of animals that weigh hundreds of pounds. More specifically, he was interested in how to fix fractures in large bones. Minor breaks could sometimes be allowed to heal in a cast, but for severe breaks, a cast is not an option—the animal has to undergo surgery. And performing surgery on a horse isn’t easy. Foals need to be able to put weight on all four legs almost immediately after the procedure, or else complications can occur—their other legs might develop joint issues, muscles can atrophy, tendons may contract. In the mid-eighties, when Watkins was training in orthopedic surgery, most foals that broke their legs had to be euthanized.

Doctors have experimented with using metal implants to fix broken bones in humans since at least the early 1890s, and by the 1970s they had begun using a type of rod with holes into which screws could be inserted perpendicular to the bone, above and below the site of the fracture. The addition of interlocking screws prevented the segments of the bone from rotating or telescoping over each other and allowed the injured limb to bear weight soon after surgery. By the early eighties, the interlocking intramedullary nail was a common treatment for people with broken femurs and tibias.

After creating his own custom tools to complete the procedure, Watkins pioneered the use of the intramedullary nail in young horses. He traveled all over the country performing the surgeries, including to the veterinary school at the University of California, Davis. He met another surgeon there, Amy Kapatkin, who had operated on the broken femur of an 18-month-old polar bear named Tundra at the Bronx Zoo in 1993.

When the vets at Hogle saw the images of Nora’s humerus, they knew that the type of surgery required to fix a bone of that size was beyond their expertise. They started locally, calling a small animal surgeon in Salt Lake City. He was interested but didn’t have the right equipment. The zoo vets expanded their search, calling and sending emails to anyone they thought might be able to help. One person had heard of Tundra and referred Erika Crook to Kapatkin at UC Davis, who in turn referred her to Watkins at Texas A&M. That’s how the horse surgeon ended up getting an email in late January asking if he’d be willing to operate on a very broken polar bear named Nora.

Watkins had never operated on a polar bear, and nobody he knew of had ever attempted to fix a humerus in one. Nora’s leg had already been broken for several days at that point, and the longer it remained untreated, the harder it would be to repair. With every day that passed, Nora’s muscles stiffened more around the broken bone. If he was going to attempt the surgery, there would be a very small window in which to arrange all the logistics and complete the procedure.

He’d consider it, he told Crook, but only if he could bring along another veterinary orthopedic surgeon from Texas A&M named Kati Glass. She knew the procedure and was familiar with the equipment, and, most important, Watkins trusted her. She began researching polar bear anatomy while Watkins set about tracking down the equipment he would need. He had the interlocking nail, but for an animal of Nora’s size, he wanted to use a plate, too, for added strength, and he’d need to have it sent to Utah.

He would also need a specific type of drill, as well as specialized screws and various sizes of medical drill bits. And he would need it all to arrive in Utah, sterilized, in a matter of days. He called the rep at his medical supplier, Johnson & Johnson, and they donated $90,000 worth of equipment, promising it would be where it needed to be by the time Watkins was ready to operate. He got the X-rays of Nora’s fracture from the vets at Hogle, but he couldn’t tell how big the cavity in the bone was and he wasn’t sure the rod would fit.

Watkins and Glass had never heard of Nora, but in the course of her research Glass learned that their prospective patient was a celebrity in the zoo world. Her dedicated fans in Oregon and Ohio would be satisfied with nothing less than a completely successful operation. Her fame added another layer of pressure to the surgery. When he operates on horses, Watkins usually has a frank discussion with the owner beforehand. He tells them that sometimes, during the course of the operation, it becomes clear that the fracture is beyond repair. If he can’t get the bone fragments to align just right or if the repair will leave the foal in pain for the rest of its life, the only humane option is to euthanize the animal. Watkins knew he couldn’t consider that as an option for Nora.

An anesthesiologist was brought in from North Carolina, and a local orthopedic surgeon was called in to assist. The equipment that had been shipped to Utah arrived on time and undamaged. The following Sunday, Watkins flew to Salt Lake City. He would operate the next day, more than a week after Nora had been discovered not moving in her enclosure.

Early Monday morning, a team of vets and keepers sedated Nora in the holding area. She was carried the short distance to the zoo hospital on a cargo net hoisted by ten people, including Randinitis and Jablonski. For Crook, the whole first hour was a whirlwind of activity, but the move was one of the most stressful times. She had been responsible for sedating Nora, and she kept a close eye on the bear for any signs that she was waking up. She was injured and unconscious, but Nora was still a 500-pound carnivore, and now she was essentially uncontained. If she woke up, the situation could get dangerous very quickly. But the sedatives worked, and the sleeping bear made it to the operating table without incident.

Nora was still a 500-pound carnivore, and now she was essentially uncontained.

Nora was positioned on the table while Crook assisted the anesthesiologist. Watkins and Glass and the other members of the surgical team scrubbed in as Nora was intubated and put on a ventilator. Crook helped attach a catheter to the bear’s ear so they could monitor her blood pressure and other vital signs while Jablonski and Randinitis stood on the other side of a window. Watkins was doing his best to focus on the task at hand, but there was a lot to marvel at. As they shaved the hair from the incision site, he was shocked to realize that under all that white fur, polar bears have dark, almost purple skin.

Nearly an hour after she was sedated, Nora was fully prepped and covered in surgical drapes, and the procedure started in earnest. Watkins cut a nearly 15-inch incision, which curved around Nora’s arm from her shoulder to just above her elbow. The team peeled back her skin and began making their way toward the site of the fracture. It wasn’t so different from a horse, Watkins thought to himself.

Once they got to the break itself, Watkins knew it was going to be difficult to get the bones lined up, which is necessary for the rod to be inserted correctly. He began trying all the things he’d learned on horses over his career, but nothing was working. It took a lot of effort, both mentally and physically, and sweat beaded on Watkins’s brow. Out of other options, he tried to tent the bone, bending the two segments up into a triangle in hopes that he could pull them back down into a straight line, but no amount of force could overcome Nora’s muscles.

*

Just outside the operating room, Randinitis watched intently from behind the glass. There was nothing she could do from her side of the window, but she felt she needed to be there just the same. She never thought of the zoo’s animals as pets, not fully, but in her mind they were like some combination of a pet, a child, and a co-worker. She felt it was necessary for Nora to know she was there, even if only on a subconscious level. Jablonski was there, too, watching as Watkins struggled to get the segments of Nora’s humerus to line up. Nora wasn’t the only animal in their care, so the keepers ducked out when they had to tend to their other charges. But keepers from other parts of the zoo volunteered to cover for them so they could watch as much of the procedure as possible.

When Watkins had been talking with the reps at Johnson & Johnson, they’d asked him what size bone saw he wanted. The surgeon hadn’t included a saw in his initial order—he didn’t normally use one for this type of procedure—but he knew that if he turned it down, he’d find himself needing one. They threw in a blade with the other equipment, and as Watkins weighed the risks of cutting into Nora’s already broken bone, he was glad they had.

It was a measure of last resort. The goal of the surgery was to repair the bone and leave it intact. Removing any material could create complications; he’d never had to do it before, and he wasn’t sure exactly how it would affect the healing process. But he’d already been working on Nora for a few hours at that point, and the longer an animal stays under anesthesia, the riskier the procedure becomes. He attached the saw blade to the drill and trimmed off a small pointy piece of the upper bone segment, the part that attached to the shoulder. It did the trick. The bones were brought into alignment, and Watkins put a big clamp on the humerus to hold it in place. He slid the nail down into the cavity and used a special tool to target the holes, inserting three screws above the site of the fracture and two below.

In a foal of Nora’s size, he would have added a plate, too. But Nora had been in surgery for several hours and under anesthesia even longer. Her vital signs were beginning to falter, and the risk of infection increased with every minute she was open on the table. Putting in a plate would take another couple of hours at least, and Watkins didn’t want to risk it. He wrapped the bone in cables that he cinched down and crimped in place, right around the break, hoping they would provide the fixation that Nora would need to heal. With a horse, Watkins would be able to dress the wound and manage it throughout the healing process. Once Nora woke up, no one would be able to touch her again without putting her under, and there was no way to bandage her wound or keep her from licking the incision site.

All they could do now was wait for Nora to wake up and hope for the best.

__________________________________

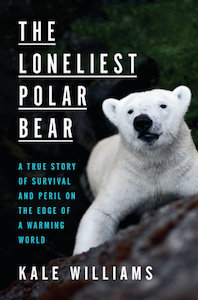

Adapted from The Loneliest Polar Bear. Used with the permission of the publisher, Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2021 by Kale Williams. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Kale Williams

Kale Williams is a reporter at The Oregonian/OregonLive, where he covers science and the environment. A native of the Bay Area, he previously reported for the San Francisco Chronicle. He shares a home with his wife, Rebecca; his two dogs, Goose and Beans; his cat, Torta; and his step-cat, Lucas.