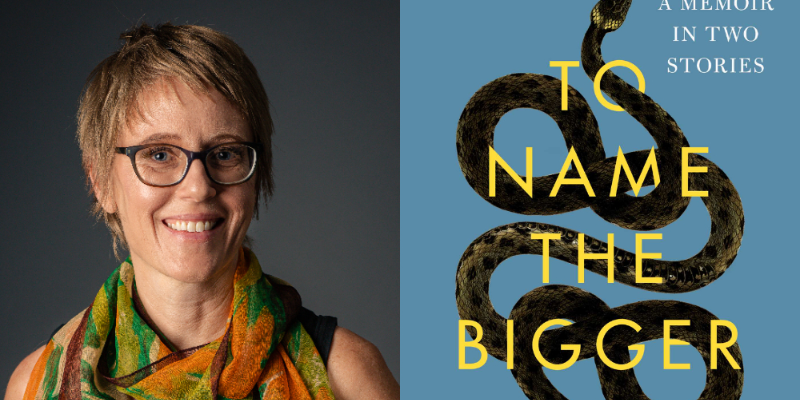

Sarah Viren on Examining the Self in Both the Past and the Present

In Conversation with Maris Kreizman on The Maris Review Podcast

This week on The Maris Review, Sarah Viren joins Maris Kreizman to discuss To Name the Bigger Lie, out now from Scribner.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts.

*

from the episode:

Maris Kreizman: I love that you get to talk a bunch about craft in talking about how to approach your past. And you mentioned Virginia Woolf’s notion that there’s a you of the past and you of the present, and those are two different people. But the thing that she doesn’t address, which is such a key component of your book, is that you in the present is still changing.

Sarah Viren: Yes. And I mean, that’s kind of key to the book too. I was writing this story about high school and I did have what felt like a static, what Woolf calls the “I now”—I am the person I am in this moment writing about the past—and there’s something so safe about that, right? I’m this static constant. But what happened in the second part of the book is that something happens to myself and my partner. We were sort of thrown into what ended up feeling like a similar situation of being trapped in lies and manipulations by a completely different person.

At the time it was horrifying and overwhelming, but craft-wise in thinking about the book, it really was helpful because a memoir is an examination of the self. Vivian Gornick has this distinction where she talks about memoir and essay, and she says that the essays uses the self as a lens to understand the world, and that the memoir uses the world as a lens to understand the self.

I think I’m doing a little of both in the book, right? I’m interested in the self, but also in the way the self helps us understand the world outside. Complicating that sense of self felt particularly rich and important within a memoir, but I think within a book like this too, that’s coming out of those really basic philosophical questions like who am I? What does it mean to be a person, et cetera.

And yeah, it is really more complicated. The self you are right now could always change. And that’s kind of the risk, but the joy of being alive is that we don’t have control over that all the time. And there can be tragic and wonderful things that happen that completely change our lives and circumstances and what we understand of the world.

MK: You also mentioned, as another impetus for writing this book, the birth of your daughter. So let’s talk about the joyful one first.

SV: Yeah. So my partner and I have two kids and my partner carried our first, our older daughter, and I carried the second one. So in some ways I had this experience of watching a baby be born, but never going through the experience of birth. And then I gave birth to our daughter.

So, I did this really interesting thing called hypnobirth where you hypnotized yourself during the birthing process. And I’m not a very woo-woo person. Like I don’t tend to think that like there’s, I very much get into like, sort of medicine and, you know, I would’ve taken an epidural, but my friend said, try this.

And I said, okay, I’ll try it. And I did not think it would work, but it did. It was pretty amazing because I have a very low pain tolerance, but I was able to sort of pass through the whole process of birth with this self hypnotizing and have very little pain. But it all went away right when she was coming out. So, the pain suddenly, I say hollowed, it overwhelmed me. But there was this amazing moment where I say in the book that I kind of felt like, I felt like God.

I talk a lot about Plato’s allegory, The Cave in the book, and this idea of leaving the cave where you’re deceived into this moment where you know what is what. And there was a sort of beautiful moment of clarity where I felt like I understood everything. Like I felt the wonder that Socrates talks about and this sort of, maybe nirvana, whatever these things that we talk about as being sort of this state that we might hope to reach.

And it was very brief, but right when my daughter was born I felt that and it was pretty magical and intense and incredible. And I think that I really clung to that in part because it helped me think about what amongst all this, talking about like what’s happening to truth, what are all the threats that are going on right now? Like how do we deal with, you know, so much manipulation and, and all of these other moments of strife in the world. I think that moment of the birth helped me remember that.

Like, but yes, but in being human, what is incredible is the potential for wonder, right? For this potential for some sort of state where we feel kind of connected to one another to God or whatever it is that you believe. And then that’s also part of our understanding of truth or whatever truth is. And so I think that I really did cling to that. It was present as I was writing the book because maybe, as you said, it felt more hopeful. It was sort of the other side of the coin.

*

Recommended Reading:

In the Freud Archives by Janet Malcolm • When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamín Labatut, translated by Adrian Nathan West • Big Swiss by Jen Beagin

__________________________________

Sarah Viren is a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine and author of the essay collection, Mine, a finalist for a Lambda Literary Award. She was a National Endowment for the Arts Fellow and teaches in the creative writing program at Arizona State University. Her new book is called To Name the Bigger Lie.

The Maris Review

A casual yet intimate weekly conversation with some of the most masterful writers of today, The Maris Review delves deep into a guest’s most recent work and highlights the works of other authors they love.