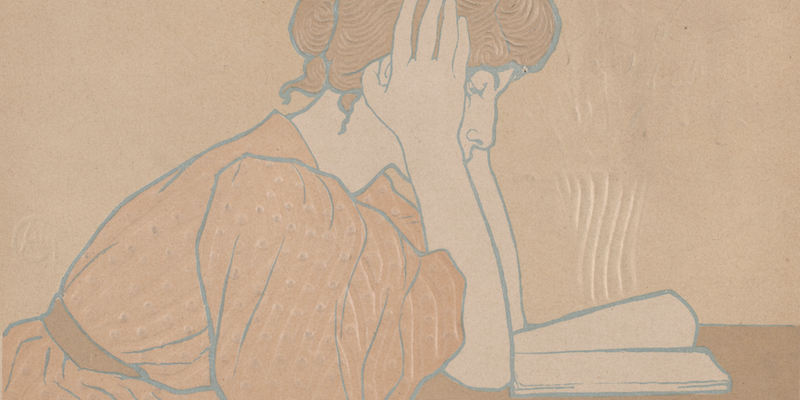

Sarah Mesle on the Power of Picturing Your Desired Reader

“Who is your girl? Where is she going?”

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Who is your girl? Where is she going? I learned these two questions from Project Runway, the fashion reality show, which I watched delightedly for several early seasons before realizing that the show’s design advice could be upcycled, as they say, into writing wisdom. Sometimes on Project Runway, a contestant would design a “look” that seemed more a novelty act than an outfit. It was at this moment that a designer might face a judge’s questions: Who is your girl? Where is she going? When a judge posed these questions, they wanted to know: Who, actually, would wear this? Where would someone wear it? The judges wanted designers to remember: Clothes are made to be worn.

If you want your writing to matter, it must hold itself accountable to real readers’ desires—and resources—for self-fashioning.

So, too, with writing that aims to be read. Reading, like wearing clothes, is an embodied act. It’s undertaken by real people, making choices in real places. Your writing decisions about diction, sentence structure, citation, compression, venue, and more matter to your reader’s functioning; they do so, much like a designer’s choices about fabric, cut, and fasteners. The key part of these questions, as writing advice, is to think of your reader on two axes: identity and context. On Project Runway they mean: Is your girl going to a party? A coffee shop? Walking, subway, or valet parking? In asking us, as writers, to envision our girls and their goings-on, I’m encouraging us to consider specifically—and with some pragmatism—our desired reader and her scenes. Picture her, your reader, in the path of her life. She is in line at the grocery store or she is at a bar. She stands over her stove. She sits alert at her desk; she lounges on her couch. Consider the style that will fit her there.

Often, I think, writers receive advice about how to write for different venues, for broad or specialized audiences, that focuses too narrowly on tips like “avoid jargon.” This advice doesn’t help writers, especially those with expert training, make meaningful decisions about what a reader needs. Thinking about where her girl is going can help a writer make better choices about diction than simply avoiding certain words. Your girl, no matter where she is and no matter what version of code-switching she may currently be employing, will always have the same vocabulary.

Whether I am at my desk or in line at the grocery store, my knowledge doesn’t change. I’ll know the same references—poststructuralism, melancholy, midi-length skirt, Jessica Wakefield—regardless. But depending on context, sometimes words work like the mention of a shared friend, and sometimes like a flex. Choosing when to use a word, and then deciding whether or not to define it (the writer Kiese Laymon has called making these decisions writing for the readers in your “first row”) can present itself like a gesture of hospitality to some girls, or an act of estrangement to others, or at other times.

Remembering to ask where your girl is going can also make significant difference to your decisions about syntax. When you really picture your girl, your reader, where is she? Is she reading on her phone, on her kindle, from a magazine, printout, or book? Does she have a free hand to hold a pen? How long can she expect to read without interruption from a train stop, her child, a pop-up ad for shoes? You can fantasize about (as I fantasize about) an infinitely rapt reader, but there are just not very many of those, despite the number of people who fantasize about achieving that state (as I fantasize about achieving it). Just like a girl with a long walk to the subway may need lower heels, a girl reading amidst distraction may need a shorter sentence, or one carefully organized around concrete nouns and vivid verbs.

As these examples hopefully show, asking myself about my girl and her destinations helps me resist the idea that, if my writing isn’t finding an audience, it’s because I need to “dumb down” my prose. When writers fail to connect with their audience, it feels reassuring to the writer, often me, to conclude that the misfire happens because of too-simple wiring in the reader’s brain. What’s more likely the case is that I have coughed out a deeply idiosyncratic paragraph whose clear-to-me intricacies looked to everyone else about as legible as an owl pellet. You can call the reluctant reader of this paragraph “dumb,” but the more likely situation is that dissecting your half-metabolized thoughts is not the science project your reader is hoping for, at this particular time, on her way to this particular destination.

These questions can also provide some guidance about being edited. An editor’s job is to understand their venue’s girl and where that girl is going. While part of the editor’s role is, like on Project Runway, to judge, once they’ve accepted your piece, an editor’s job is to work with you, behind the scenes, on tailoring and styling, because they believe in their girl and they believe in what you have to say. Editing can go best when a writer sees an editor as an ally in finding the best fit.

What these questions won’t do, though, is provide writing advice that’s definitive or prescriptive. It can’t tell you what mode of writing will necessarily suit your reader, any more than a judge could tell a Project Runway contestant what one outfit would always make a girl feel comfortable, or whether “comfortable” was how she always wanted to feel. After all, ease might not offer comfort. Many people in the midst of busy life want to remember the tremendous capacity of their minds for rigor. Speaking for myself, in many contexts I like high heels, tailored dresses, and densely wrought sentences. I also have soft pants in three levels of softness and reading materials that match each one. Which version of my moving selfhood does your writing aim to shape, display, hail, endorse, reform?

The point of this advice, finally, is to try to write so that my girl can feel recognized as herself in where I ask her to go. Your girl, your reader, may or may not be moving physically toward different places. But regardless of whether she is reading at the coffee shop, her kitchen table, or a bar, she may hope her reading brings her closer to different collectivities, or different affinities with them. She is moving toward a new version of herself, or affirming a part of herself she values. If you want your writing to matter, it must hold itself accountable to real readers’ desires—and resources—for self-fashioning.

__________________________________________

Reprinted with permission from Reasons and Feelings by Sarah Mesle, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2025 by Sarah Elizabeth Mesle. All rights reserved.

Sarah Mesle

Sarah Mesle is a professor of writing at the University of Southern California. The former senior humanities editor at the Los Angeles Review of Books, where she is also a regular contributor, Mesle is the founding coeditor of the LARB channel Avidly and the short-book series Avidly Reads. Mesle’s writing has also appeared in venues ranging from Studies in American Fiction to InStyle to The New York Times Magazine.