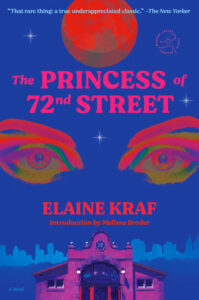

Sanity Is Relative: Melissa Broder on Elaine Kraf’s The Princess of 72nd Street

Considering the Blurred Boundaries Between States of Mania and States of Spiritual Grace

The Princess of 72nd Street, first published by New Directions in 1979 when Elaine Kraf was forty-three, is an avant-garde tale of one woman’s seventh manic episode—a period of euphoria and hallucination, which she calls her “radiance”—and her desire to love from there, write from there, and perhaps, least tenably, live from there.

Ellen is a portrait painter who, as “Princess Esmeralda,” rules the land of 72nd Street on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in the 1970s. When she isn’t being checked into Bellevue, Roosevelt Hospital, or St. Vincent’s to be treated with Thorazine and Stelazine, she governs her fiefdom of filmmakers, watermelon salesmen, musicians, shopkeepers, bartenders, and bricklayers by watching over them, sleeping with them, and occasionally, dancing topless with them.

The Princess of 72nd Street asks progressive questions about personal freedom, mental conditions, and self-governance. Who is entitled to hold power over the inner world of another? What defines sanity? Must a functional society be rooted in consensual reality? The novel also explores the question of how much happiness we are allowed as individuals, and the line between mania and a state of spiritual grace. While Kraf does not always provide clear answers to these questions (the human psyche is a nebulous realm, and this is literature—not a textbook—after all), the novel’s inquiry is ahead of its time.

One of the most stunning feats of The Princess of 72nd Street is that our narrator is always a reliable one.Apart from perpetrating a Robin Hood-like theft from a local market (she steals goods and then distributes them to her “subjects”), Ellen doesn’t appear to cause any harm to others during her radiances. She is eccentric, dressing in costumes that have her taken for “a hooker, Sabra, American Indian, actress, ballerina, witch, holy saint, mother, girl, mystic, ethereal spirit, bitch, earth goddess, and more.” A revolving door of men enter and exit her bed, including an Argentinian pianist, an attorney, an illusionist, a friend’s husband, a doctor, and a vine-like man who smells of spices (not to mention an artist ex-husband and an academic boyfriend who came before them). For the Princess of 72nd Street, the “bubbles” and “feathers” and “white moths” of radiances are meant to be shared, not kept to oneself. She longs to share her joy with society, but society is not ready for this level of liberation—carnal, material, or otherwise.

“People like to pretend that radiance is something else when they see it,” says the Princess, who describes the injections that terminate her episodes as the doctors’ attempts to “make me stop bothering everyone with my happiness.” The characters in Ellen’s orbit believe that it is their right and responsibility to constrain these periods of mania—beatific experiences where “orange flowers” grow from her body and joy cracks out of every “pore or petal or cell.” Yet, is it their right?

Complicating this question is the fact that none of the auxiliary male characters in the novel are particularly sane themselves. There is Auriel, an illusionist who fakes his suicide. There’s Peter, the painter who has an emotional allergy to plums (the result of his girlfriend’s obsession with using them as the subject for her own paintings). Ex-husband Adolphe is ravenous for success and has nervous breakdowns when his work involving a traffic light appears to be not only copied but improved upon. Ex-boyfriend George prohibits laughter and singing, and rips rags and foams at the mouth when challenged. In spite of their own madness, they single out Ellen as the insane one.

Such ambiguity is underscored by George’s psychiatrist, Doctor Clufftrain, who is the least sane character of all. Clufftrain sees patients around the clock from 6 a.m. until 3 a.m. He trembles, fears heights, and has no boundaries between himself and his patients. He instructs them to run his errands and treats them as his alter egos. He prescribes Ellen a mysterious drug that causes her to faint and throw up. It is unsurprising, then, when the doctor ultimately has a full psychotic break, a turn of events that articulates the question: Who is really an expert on mental health? Is the Princess experiencing illness when in her radiance? When the authority is sicker than his patient, her diagnosis may be seen as a sane reaction to an ailing society.

And yet, despite Ellen’s desire to stay in a state of radiance eternally (who wouldn’t want to stay in that ecstatic realm where the body is “light as a flower” and one’s hair seems to “fly up and outward like wispy silk”), the Princess must concede that her beloved state is unsustainable.

Both the Princess and Ellen tell the reader the exquisite and ugly truths of the world exactly as they see it.As Ellen is about to enter radiance seven, she writes herself notes like DON’T LET STRANGE MEN INTO YOUR APARTMENT and MONEY IS THE MEANS OF BARTER in order to preclude behaviors that could get her hospitalized again. She feels an unsafe lack of pain during periods of peak radiance, and awakens with black-and-blue marks, scratches, and a lump on her head. She acknowledges the dissonance created by her promiscuity during radiance and her belief in monogamy.

She finds the spiritual ranting of her cherished illusionist Auriel—the only person to whom she has revealed her princess status—boring. As Ellen, she longs for a pedestrian husband with money. And, while she resists the desolation that follows her radiance, longing for her fear to be turned into “mist” and for the return of “doves,” and to be part of “the vision of stars” and to remain “a child forever,” Ellen ultimately chooses to ground herself on Earth.

Whether she is the Princess, full of radiance and flooded with a feeling of “small bells ringing and showers of light,” or simply Ellen, dropped into the pit of depression, one of the most stunning feats of The Princess of 72nd Street is that our narrator is always a reliable one. One might call into question the reliability of a character with the kind of magical thinking that leads to dancing topless in Riverside Park for “all of life, all living things and for the sick to make them better,” or who believes the red light of a yacht is shining just for them. Yet, both the Princess and Ellen tell the reader the exquisite and ugly truths of the world exactly as they see it. Sane or insane, this is more honesty—imagistic, emotional, and interpersonal—than is conveyed by so many of literature’s narrators.

__________________________________

From The Princess of 72nd Street by Elaine Kraf, introduction by Melissa Broder. Copyright © 2024. Available from Modern Library, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.