Samuel G. Freedman on What Hubert Humphrey’s Fight for Civil Rights Can Teach Us Today

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

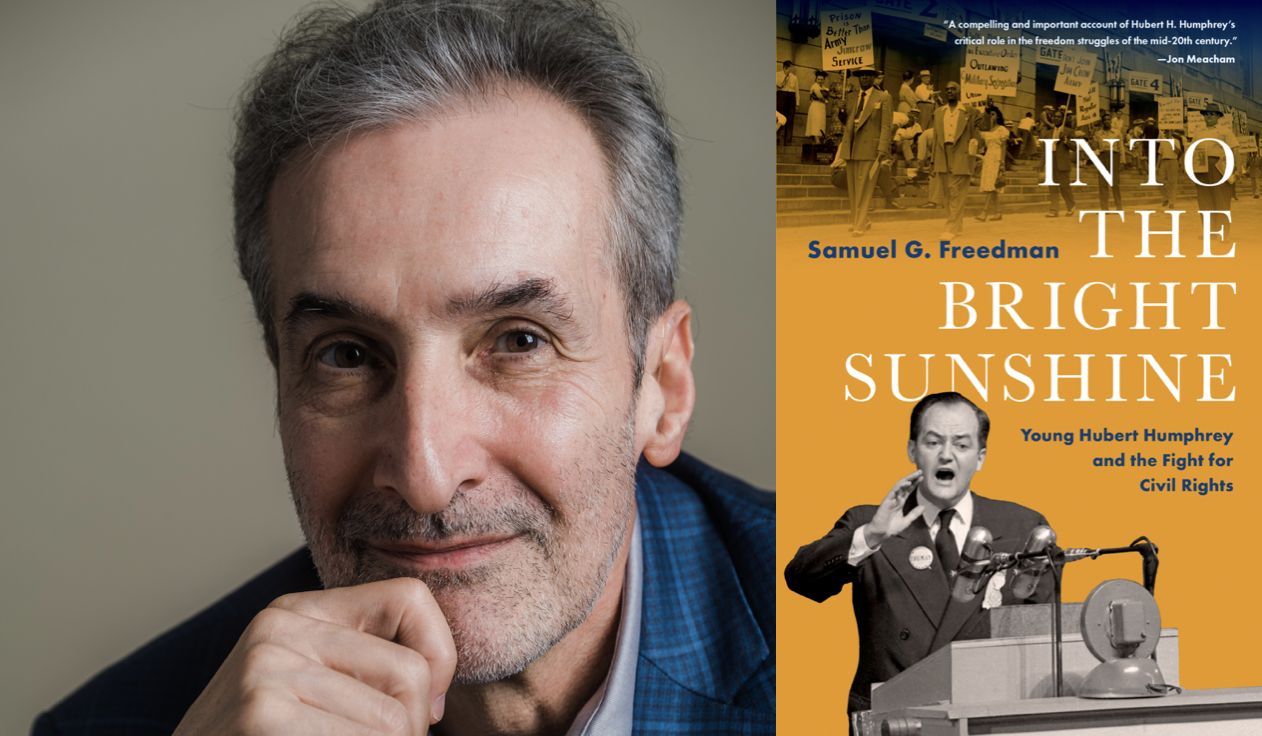

Award-winning journalist and professor Samuel G. Freedman joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to talk about what progressives today can learn from an unexpected source: Democratic politician Hubert Humphrey. Freedman explains how today’s battles against far-right bigotry parallel the fight for civil rights Humphrey engaged in alongside Jewish and Black Americans in the 1940s. Freedman talks about the importance of progressive alliances and reads from his new book, Into the Bright Sunshine: Young Hubert Humphrey and the Fight for Civil Rights.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

Whitney Terrell: Hubert Humphrey is probably best known for losing the ’68 presidential election to Richard Nixon. But your book focuses on the young Hubert Humphrey before he became Lyndon Johnson’s VP, even before he was a senator. What attracted you to that territory?

Samuel G. Freedman: That’s a great question, Whitney. Initially, I started this book in January 2015. And it’s very relevant to remind people that at that point, Barack Obama was in his second term. We’re a few months away from marriage equality being declared a constitutional right by the Supreme Court. I thought I was working on filling some holes in history and in biography. The whole of people knew about Humphrey from his mistake and catastrophic support for the Vietnam War and his several failed runs for president. And there’s the gap in history that assumed that the civil rights movement began in the mid-50s, with Brown vs. Board of Education and with Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, and the Montgomery Bus Boycott—there had actually been a really important decade of activity in the 1940s that sets the table for everything that comes later. And that felt like enough to me to be filling those two gaps.

But then November 2016 happened, and we know what happened then. I realized I was writing about current events. The battle that Humphrey and his allies were fighting was partly directly about civil rights which, at that time, was understood to mean not only the rights of Black Americans, but particularly the rights of Jewish Americans and even Catholic Americans as well, all of whom were the objects of varying degrees of discrimination by the white Protestant majority in this country at that time. But broadly, what Humphrey was involved in was a fight for interfaith, interracial, inclusive democracy against—and these are the exact terms used in the 1940s, too—white supremacy, Christian nationalism, and America first-ism. I was struck so often at the parallels between the 40s and the years we’ve been living in during the Trump era. And so that gave me an additional level of commitment and incentive to do the book as well as I could do it. Because, if I executed it the right way, it was going to be more than filling those gaps. Even though that would have been plenty of reason to validate the years of work on it anyway.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: Sam, am I remembering right that you came to Minnesota in the fall of 2016 to begin researching it?

SF: I began in 2015. My first trip to Minneapolis to start to go through Humphrey’s archived papers at the state’s Historical Society was in June of 2015. And I came out a few more times that summer, both to work in the archives and also because there were only a handful of people I could interview who actually had been firsthand involved with Humphrey’s political life in the 40s. I was not interested in secondhand memories by people who knew him later. But there were a few people who I talked to literally the year before they died or the year before they fell deeply into dementia. I was doing some of that that summer.

And then I was fortunate to have a sabbatical semester from Columbia Journalism School in the fall of 2016. That allowed me to then get into that kind of day by day sitting in the archives. I can’t say that I did the exact Robert Caro thing of turning every page, but I turned a lot of pages.

VVG: I think that’s what I’m remembering. We were sort of passing ships in the night that semester.

WT: Yet another Minnesota-oriented podcast subject, I would note.

VVG: We’ve got to catch up with Kansas City sometime.

Early on in the book, Sam, you describe Hubert Humphrey’s encounter with a man named Otis Shipman, who was Black, and who was building a road near Humphrey’s childhood home in South Dakota. And you point out that this is really the only meaningful contact that Humphrey has with a Black person until he goes to graduate school at LSU decades later. So how does a person with that background become a champion for civil rights?

SF: That’s kind of the question that drove the whole book, Sugi. My good friend at Columbia Journalism School, Michael Shapiro, who’s also an author, always says that a book has to be driven by a question. And the book has to pursue the answer to that question. For me, the question was, “Why does this very white guy from this very white place care so much about Blacks and Jews?” And I think a clue to that is with his encounters with an 11-year-old boy with this Black road crew that comes from Omaha, Nebraska, up to the grasslands of eastern South Dakota, to put down the first gravel road near Humphrey’s hometown. They’re certainly a curiosity to the town’s people. But Humphrey has a different kind of curiosity. He goes out to meet them, and he kind of befriends them and they befriend him. And he still remembers this encounter decades later when he’s dictating recollections to his communications director that that man is going to shape in time for his autobiography. There’s kind of a mythological power to me of that moment. It doesn’t predict the rest of his life, but it says something about Humphrey’s temperament, even at a young age, but then you’re right.

Fast forward from 1922 to 1939, when he goes off to grad school at Louisiana State. And Humphrey, at that point, has only lived in overwhelmingly white Protestant places—in South Dakota or in Minneapolis, a couple of months in Denver to go to pharmacy school. And he’s been oblivious at that point to a great deal of the turmoil around Minneapolis and the University of Minnesota involving racism and antisemitism, a good deal of which was practiced by the university’s own president. People who want to find out more about that should look at an incredible online presentation called “A Campus Divided” by the scholar Riv-Ellen Prell.

But Humphrey– First of all, his college is interrupted for five, six years by the Great Depression. He has to drop out and help his family survive economically. He comes back, he’s married, he soon has a baby. He is so busy catching up and trying to finish his bachelor’s degree that he’s oblivious to these battles. And he’s also—typical of many liberals of his age—oriented around FDR’s economic-oriented New Deal programs. The New Deal doesn’t think in terms of racial inequality, it doesn’t think in terms of religious prejudice. It centers economic class, for better and for worse. And so Humphrey then goes to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, solely because they’re offering him 400 bucks at LSU to be a graduate assistant, and he really desperately needs the money.

WT: I have to say real quickly, as a former graduate student, it was fun to read the parts of him scraping along the teaching assistantships and all the other stuff that he had to go through. You don’t imagine a presidential candidate having to do that. But he did.

SF: Yeah, 400 bucks for TA-ing classes. His wife, Muriel, was normally working but they had a baby daughter, Nancy. She would make sandwiches at home and either go to the campus or send them with Hubert to sell to his classmates for a dime or a quarter, whatever they could get for a ham sandwich. That was part of how they managed to make the rent. But Humphrey goes and, for the first time, he’s plunged into a Jim Crow society. And it’s not just that he sees the separate waiting rooms and water fountains and the back of the bus, but he really remembers these individual degrading moments. Black pedestrians crossing the street too slowly for the satisfaction of a white motorist who just reviles him with the N word in front of everybody. It’s a complete humiliation. And that stays with Humphrey, those kinds of episodes. And then he also makes Jewish friends for the first time in his life, including a debate team teammate, who tells Humphrey about having five uncles who are trapped in Eastern Europe, under Nazi control, all of whom are going to be exterminated. That’s the beginning of Humphrey—at a time when America is very isolationist—really understanding the vulnerability of Jewish people.

And then what ties it all together—this is really remarkable to me—is Humphrey does a seminar during the whole academic year with a professor named Rudolf Heberle. And Heberle is this one-eighth Jewish, anti-Nazi sociologist, who had begun studying—in the early 1930s—the process that Germany went from being a democracy to a dictatorship because that question, “How could that have happened?” tormented him. And he’s kicked out of Germany for that and his partial Jewish ancestry, even though he’s converted to Christianity long ago. He is penniless, he’s scrambling to find somewhere to work and settle his family and ends up in Baton Rouge at LSU.

And in the class Humphrey has with him Heberle, he’s talking about his research, which he’s in the process of writing in a book form. Heberle talks about his family’s personal experiences, and Heberle draws a direct parallel between the plight of Jews in Nazi Germany and Blacks in the Jim Crow South. And these experiences that Humphrey has in Baton Rouge just give him a moral vision that he didn’t have in that same way before. They don’t replace his concern with economic inequality but they map on it and for him through his whole career. It’s not like you have a choice between dealing with economic and class issues and dealing with racial and religious bigotry. He sees them as part of a greater liberal whole. And that’s what he brings back to Minneapolis with him.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Han Mallek. Photograph of Samuel G. Freedman by Gabriela Bhaskar.

*

Into the Bright Sunshine: Young Hubert Humphrey and the Fight for Civil Rights • Breaking the Line • Letters to a Young Journalist

OTHERS:

Robert Caro • Michael Shapiro • A Campus Divided by Riv-Ellen Prell • Sam Scheiner • Cecil Newman • Charles Lindbergh • Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota • The Call • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 6 Episode 6: “Nancy Pelosi’s Majority: Matthew Clark Davison’s San Francisco Take on a National Leader” • “75 years ago, Hubert H. Humphrey called for Dems to ‘walk into the bright sunshine of human rights’” by Cathy Wurzer and Gretchen Brown | Minnesota Public Radio

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.