Samuel Amadon on Self-Reinvention and Trusting Your Own Style

Peter Mishler Talks With the Author of Often, Common, Some, And Free

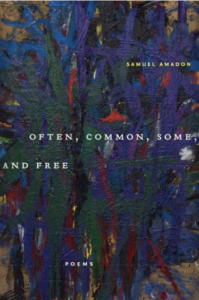

Samuel Amadon is the author of Often, Common, Some, And Free (Omnidawn 2021), Listener (Solid Objects 2020), The Hartford Book (Cleveland State 2012), winner of the Believer Poetry Book Award, and Like a Sea (Iowa 2010), winner of the Iowa Poetry Prize. His poems have appeared in The New Yorker, The Nation, Poetry, American Poetry Review, Kenyon Review, Ploughshares, Lana Turner, and elsewhere. He is the author of four chapbooks, including Each H from Ugly Duckling Presse. He edits the poetry journal Oversound with Liz Countryman, and directs the MFA Program at the University of South Carolina.

*

Peter Mishler: What is the strangest thing you know to be true about the art of poetry?

Samuel Amadon: I think about how language in a poem serves multiple functions simultaneously. That’s quite clear in a poem that rhymes or is written in a regular meter, but it’s true of language in poems in general. Language serves meaning, form, aesthetic, voice, mood, and more all at once. Those varying purposes are often at odds with each other, and I think as a result, they create a kind of capacious interior to a poem. And so, what’s strange about poetry is that what we perceive of meaning, form, etc., in a poem’s language are expressions or evidence of that interior, rather than a means of accessing it. It’s like if you’re reading a poem that feels really palpable and present, that means there’s something there you can’t touch.

PM: I wondered about your inclusion of Cy Twombly’s work on the cover of Listener. Could you talk about the relationship between your work and painting?

SA: I love the Twombly cover Lisa Lubasch and Max Winter selected for the cover of Listener. Their press, Solid Objects, makes books with a distinctive sense of design that I really admire. I felt like the Twombly cover was perfect the first time I saw it, but I don’t really know how to say why. I think my relationship with the painter of my other three book covers, LA artist Spencer Lewis, has a lot more to do with my work in general. Spencer’s my oldest close friend. We’ve been friends since we were six years old. We grew up a couple of blocks from each other, went to school together, worked the same jobs, and played football together in high school.

Spencer’s been a painter longer than I’ve been a poet, and in my youth, I spent plenty of days sitting in the garage behind his parents’ house, watching him paint, sometimes with spray paint, with house paint, with what he had around. I think it’s fair to say that I developed something basic in my understanding of artmaking in those hours. That it’s serious and messy. That it’s essential. That what makes it essential is not just unspoken, but unspeakable. Those are the years when I started writing. Our close friend Kristoffer Harris really got me into poetry, and my ideas of being a poet are also still linked to what we talked about back then and how he thought about things in a lot of ways, but in terms of visual art, the feeling of watching Spencer make paintings is tied to the way I feel when I make poems.

“I love the feeling of a distracted thought I’m having while reading showing up in the book in front of me.”

PM: Can you tell the story of how you became interested in Robert Moses’ work and the other structures referenced in your work—in Provincetown and Penn Station?

SA: When I started working on Often, Common, Some, And Free, the long poem “The Pennsylvania Station Sequence” was one of the first things I wrote. I’d spent quite a bit of time in Penn Station, both coming into the city from Hartford and on the subway when I lived in the city and worked office temp jobs in that part of town, and I, for whatever reason, never knew there’d been this massive structure that was destroyed to make way for MSG. I was living in Texas, missing New York, and I read something about the original Penn Station somewhere, and it occurred to me that a different poet might read something like the article I’d just read, and then read up on the subject in order to write a poem or a book or whatever.

That wasn’t at all how I wrote a poem at the time, but I had published two very different books, The Hartford Book and Like a Sea, one narrative and one experimental (in the terms we used in those days), and I’d started to see writing in new ways, transforming my aesthetic, as something I should stay interested in. I wanted to try writing like a poet that wasn’t me. What came out of that idea was this punctuationless series of polyvocal monologues where multiple speakers compete with each other in the same sentence, trying to tell the story of the creation and destruction of Penn Station, but also running into my own life and other concerns. I say multiple speakers, but they’re all really me, talking on top of myself several times over. Or you could think of it as one speaker sometimes speaking multiple sentences at once.

In the original version of the book, which I wanted to call Tourism, that poem was one of several aesthetically distinct sections, and in each I was writing in unfamiliar forms. Poems in iambic pentameter. Poems in syllabic patterns. The book’s formal aesthetic was meant to transform again and again. It was several years later that I started writing the Moses poems, while reading The Power Broker and All That is Solid Melts Into Air, and one thing that’s clear from those books is that Moses transformed the city, destroying communities and people’s lives, mostly because he could. And it was strange to me to think of all this enormous infrastructure in New York being anything other than permanent—being instead something that someone thought up, a way they imagined altering the world.

I thought I was writing a new book when I started those poems, but then I pushed them into Tourism, kicked some other things out, and ended up with Often, Common, Some, And Free. There’s a tension in the book between those impulses: to transform and to hold still. I’m interested in the way that a poem can hold a conflict in, or even under, its lines. And so, if there are multiple versions of me struggling with each other in the lines of Penn Station, the Moses poems do something similar with a kind of unreliable persona poem, where I’m talking occasionally as Moses but not sticking with it. Or something similar is happening in how I’m being kind of inattentive to my subject or arbitrary in what I’m writing about. I’ve never been to Jones Beach. I’ve never been to these swimming pools I write about. There’s conflict between me and my subject, and it’s taking shape inside the poem.

PM: Would you be willing to say more about that gesture of being inattentive to a subject while writing about it? If you think about it now, can you trace any kind of conscious path in your learning, your reading, your writing, your aesthetics that makes sense to you why this “inattentiveness” might occur in your work?

SA: I don’t know if this is it, but I love the feeling of a distracted thought I’m having while reading showing up in the book in front of me. Like I was on the subway once, reading Proust, and thinking about what I was going to do with the Powerball millions from the Quick Pick in my shirt pocket, when Proust’s narrator said something along the lines of “someone who spends their winnings before the numbers are called.” That doesn’t even sound believable to me now. And I’ve had this experience reading poetry collections where my mind will drift to some subject not previously mentioned in the book, and then a poem on that subject appears. I don’t know if those are accidents or not, but I’m interested in what happens when I’m not paying attention.

PM: Would it be fair to say that to some degree you are interested in procedure/proceduralism as an aesthetic value or approach?

SA: Yes, absolutely. A lot of the work I did in my first book, Like a Sea, was the result of constraint-based procedures or chance operations, and I’m a Jackson Mac Low fan. I haven’t really been doing that kind of work lately, but I think it has informed the way I think about a book, how the book works, and how I go about putting it together. I usually have a plan for what I want a book to be, but it’s there in order to make a space for me to be reckless or instinctive in the particular poems I’m writing. And it shows up formally in individual poems as well. I don’t really think of procedural work or traditional prosody as being that different.

If I’ve got rules, I’m following them, even if they aren’t apparent to everyone else. In both of these new books, I have long poems in un-, or minimally, punctuated syllabic patterns—“Descend, Descend” and “Spy Poem.” In both cases, there’s a big Richard Howard-esque pattern in a tabbed-around stanza on the page and a sentence that is totally out of control. Formal constraint makes sense to me as a counterpart to chance or surprise or some wilder element in the poem. The version of me that’s counting syllables makes room for the version of me that’s talking to strangers on a park bench or switching subjects mid-sentence in whatever it is I’m trying to say.

“I think changing how you write can be a way to sustain a career.”

PM: Could you talk a little bit about your journey in terms of making poems in this way, with some level of procedure? I’d be particularly interested to know how you were introduced to something like this–maybe this comes back to watching Spencer Lewis paint.

SA: In Timothy Donnelly’s workshops, he’d give us prompts for procedural exercises to try in addition to our other writing, and I was in his class at a point when I was actively looking for new ways to write, and it was a good introduction to this kind of work. We did diastic readings, homophonic translations, this technique called a negative image (where one writes a poem by finding the opposite for each word in someone else’s poem, moving word by word, and then revising with the original poem out of the way.) I got into it, and started coming up with my own procedures, some deeply weird. But mostly, as someone who was trying to get away from writing a narrative poem with a particular voice, which is what I had done up to that point, it made sense to me to put a bunch of rules in my way. Doing procedural work is when I began viewing self-reinvention as a natural part of my writing process.

I think changing how you write can be a way to sustain a career. I mean a career as in the actual writing part, not that other thing. I think trying to write in new ways can keep the work meaningful and challenging and surprising, and maybe can help prevent you from becoming a caricature of yourself. I love when you find a poet doing something you don’t expect them to do. Especially an older poet. I worked with Richard Howard during the time when he was writing the Park School poems that are collected in A Progressive Education, and I think people responded so much to that work partly because it was such a surprising shift—to hear Richard speaking in the letters of a roomful of precocious schoolchildren—but also because that shift opened up something important to him that he wouldn’t have gotten to otherwise.

I guess I was also interested in seeing how far I could push away from what I’d done and still sound like myself. Which brings me back to Spencer’s work. There’s no mistaking one of his paintings for someone else’s. Look at his website. He’s not trying to make those paintings look like Spencer Lewis paintings. Your own style, or whatever, is inescapable. That’s really clear with his work, but I think it’s generally true. I find students, when they start putting a book together, are often really worried their poems won’t collect together or sound right together, especially without “a project,” and there’s a concern about establishing a style. But I think a lot of the time, if someone takes it for granted that they have a style, and they’re willing to take some leaps in what they’re doing, we can get a fuller and, possibly, clearer sense of their aesthetic in having to put it together across a varied set of poems.

PM: I’ve always thought of your work as interested in the quotidian, the day-to-day, something more down-to-earth. To what extent do you think that’s true? Do you see yourself that way as a poet?

SA: Absolutely. As a subject, I often start talking about daily things when I start writing, and that’s been the case since I first started writing. I’m interested in that aspect of the New York School, and I have a whole unit in one of my undergrad writing courses on dailiness. This is a little hard to explain, but I have some image of being alone in my house in the middle of the day, sunlight moving across the floor, some Richard Scarry set of characters moving around the neighborhood, that feels linked to what I think I’m doing when I’m writing. I’m interested in routine, and patterns, and that’s part of where this aspect of my work comes from as well.

I think what you’re referring to also might be an aspect of how I talk. What my sentences are like. My voice. The way I sound in a poem is the way I sound in my head. It’s the way I sound in the classroom, on the phone, in a faculty meeting. And, even when I’m taking on language that isn’t “the vernacular,” there’s a sense of playing with other people’s words that makes this aspect of my own voice clear by comparison. That’s what I’m talking about in my poem “At McCarren Pool,” when I say: “Here I am with all the words I didn’t used to know.” That voice is the part of me that I don’t even know is happening when I write, and that I couldn’t get away from if I tried.

PM: Speaking of voice, can you talk a little bit about two elements present in Listener both the use of declarative, simple sentences as well as juxtaposing these sentences by creating contradictory statements, one against the other?

SA: It felt to me like a different way to get at that burst of energy that I get in Penn Station where the speaker is talking multiple sentences at once. Like in having a contradictory statement follow what the speaker just said, it was a different way to keep twisting my voice. I think it comes out of what I’m trying to do in Listener with this hyper-present lyric I. In those poems, the I is meant to be so present, so everywhere, that it feels almost invisible. And if that’s the case, then why can’t my ideas contradict each other? My speaker’s not really there enough to stop them.

PM: To what extent are you interested in documenting your lived experience?

SA: I am interested in that. I mean it’s an impulse that gets into my poems whether I mean to have my life in there or not. Most obviously in Penn Station, where my lived experience sort of takes over the narrative. But even in a poem like “Fenway Court,” where I was writing about the Gardner Museum robbery, which has almost nothing to do with my life, and I ended up talking about lying under a hammock at my great-grandmother’s house, listening to tapes on my yellow Walkman. I like the feeling of thinking about my life. In Often, Common, Some, And Free, a lot of the experience I’m writing about involves travel or walking or moving around cities in some way or another.

I’m walking around Houston or up and down Manhattan, riding the train, the subway, driving around Texas, or Liz and I are finding our way through a crowd in the dark in Rome. And I guess it’s still part of what I’m doing in the poems I’m writing now. Since 2016, I’ve been writing a book of sonnets, Divers. It’s a project my lived experience has shaped directly—in that, I have a lot of varying responsibilities at this point in my life that take up a lot of time and that require different kinds of thinking. I don’t have a lot of time to write. Teaching, working with MFA students, administrative responsibilities, childcare, the pandemic, working on our magazine Oversound, and everything else, make working in 14 lines make sense, because it’s just right there when I’m doing it.

But the experience I’m documenting is quite different now too. It’s not some unbelievable story I’m retelling, but rather, me in my backyard, everyday—with poems coming out of routine, dailiness, gardening, standing on my porch with a thought, day after day, year after year. And because of the way these sonnets have been written, I look through them all and feel the years I’ve been writing them. I don’t know how it’ll read to other people, but to me, it feels a little more like I’m documenting something, rather than just talking about my life.

PM: Did you end up having to determine whether poems were right for Listener or Often?

SA: Well, first I should explain that the process of writing these books was very different, and their path to publication even more so, and while they came out relatively close together, I wrote them during different periods. The first version of Often, Common, Some, And Free was a finalist for a book prize in 2009, and Rusty Morrison accepted the book at Omnidawn in 2018. I wrote and rewrote the manuscript repeatedly, and I sent it out plenty. I kept thinking I was starting a new book, and then pushing the poems into Often, Common, Some, And Free, losing my original idea of a book driven by aesthetic variety, and developing a project that’s a little harder to pin down.

Listener was very different. I wrote most of the poems over a period of time after Liz Countryman and I had our first child. I had some time off teaching, and we were sending our daughter to daycare from 9-12:30. I’d go into my office at the University of South Carolina, sit down, and immediately start writing until it was time to pick her up. Our department’s housed in a brutalist tower that plenty bad can be said about, but that I also kind of love. I like riding the elevator, saying hi to people. And it just worked for me right then to be going into the office to write poems. All business. Solid Objects took the book within a week of me sending it in to them, and we moved forward from there. It was a while before the book came out, but the process of writing and publishing these two manuscripts was very, very different, and I wasn’t really moving poems between them.

PM: Although the two books—which came out in some proximity to each other—were written at different times, is there any extent to which they end up conversing, or do you think they say something about a “then” (when you were working on a large part of Often) and a “now” when you were writing poems for Listener?

SA: I think place is one way to think about the books in relation to each other. The poems in Often, Common, Some, And Free range from New York to Texas to Rome, everywhere but Hartford, where I’m from and where I’ve written about extensively in the past. The variations in form and subject matter of the book mirror that movement. As I said, it’s a book I wrote over years when I was traveling a lot and living in new places, and it feels like interstates and airports and walking around new cities to me. Listener, meanwhile, feels “neighborhoody” and suburban to me, all green and full of sidewalks and daylight.

Part of what I’m doing with the lyric I and the speaker in Listener is reassembling myself in this place where I live now and will live, hopefully, for a long time. While my aim in Often, Common, Some, And Free was to write poems in ways I normally wouldn’t, I’m trying in Listener to tap into aspects of my work or my practice that have been there through all the books, maybe some more and some less apparently. Sound and rhyme. My speaker’s persona. Playing with allusion. Often, Common, Some, And Free ended up being a book about me working to keep still, and Listener is a book where I try to grow something in the place I landed.

__________________________________

Often, Common, Some, And Free by Samuel Amadon is available via Omnidawn.

Peter Mishler

Peter Mishler is the author of two collections of poetry, Fludde (winner of Sarabande Books' Kathryn A. Morton Prize) and Children in Tactical Gear (winner of the Iowa Poetry Prize, forthcoming from the University of Iowa Press in Spring 2024). His newest poems appear in The Paris Review, American Poetry Review, Poetry London, The Iowa Review, and Granta. He is also the author of a book of meditative reflections for public school educators from Andrews McMeel Publishing.