Same As It Ever Was: Orientalism Forty Years Later

On Edward Said, Othering, and the Depictions of Arabs in America

“Why do they have to show that? That—that—violence,” I said to my mom hours later, burying my face in my pillow, unable to sleep, my little body convulsing with this strange grief.

In the packed dark of our local theater, eleven years old, I’d been reeling, gripping the armrests in terror as Raiders of the Lost Ark flashed across the huge screen. The swashbuckling Indiana Jones had somehow escaped a trap-filled temple in Peru with the golden idol in hand, but his local guide hadn’t. The image of a wide-eyed brown-faced man with a spike piercing his forehead had seared itself in my mind, but now they were somehow in Cairo, and Indiana, having escaped a chase in the casbah, found himself face-to-face with a black-cloaked, scimitar-wielding Arab. Smiling, laughing even, the man flung and swung the comically large sword from hand-to-hand. World-weary, Indiana pulled out his pistol and blew him away. The crowd around me erupted in cheers. Was I supposed to laugh? Before I could react, we were off again, with our American hero, between local “savages” and Nazis, until in the fury of the opened ark, the bad guys’ faces literally melted off. Walking out of the theater, I did everything I could to hold back sobs.

Growing up Arab American in the 1980s, I couldn’t escape these depictions of Arabs as vile, cruel terrorists. I was confused why so many movies I watched featured a bloodthirsty Arab vanquished by white American heroes. It wasn’t just Raiders, of course, it was also the weird creatures of the Tatooine desert in Star Wars, the vicious Sand People, who seemed more than a little familiar. And later, The Black Stallion Returns (1983), and not too long after that, the runaway time-traveling hit, Back to the Future (1985). What were Libyans doing in Hill Valley California, and why did they have plutonium? It was such a non sequitur that we never asked what they were doing there. Of course, the movie wanted us to say, those wretched Libyans! And like the Egyptian sword-wielder who was really a white stuntman, a whole parade of terrorists played by Israeli actors in “arabface” were trotted out in movie after movie produced by the Israeli-led Cannon Films.

Later, when I read the work of Edward Said and Jack Shaheen, I learned that my experience—and these films—are not the exception. Shaheen’s Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People (2001) looked at nearly 1,000 films and found only a dozen that depicted Arabs in a complex or positive way. Watching television, it was more of the same. I secretly loved the wrestler “The Iron Sheik,” who wore a keffiyah, robe, neat mustache, and played the heel. He was Iranian, actually, but he was as good as Arab to me (shout-out to my Iranian brothers and sisters). When he palled around with the Russian Nikolai Volkoff, I thought of the Russians as odd comrades. Of course, The Iron Sheik played the heel. Whenever the crowd began to jeer him—or anyone—I felt something churn in me. Some kind of fire ignited in my head. I was drawn to the one who was hated. Whether the person was black or brown or queer or just strange, I wanted to stand beside them.

Occasionally, hanging out with my dad watching TV, he’d proudly point his finger at a visage or a voice and reveal their secret identity: “Casey Kasem: he’s one of the brothers!” “Ralph Nader: good Lebanese boy!” “Helen Thomas: one of the sisters!” I would feel invited into a secret world, where some people passing as normal were secretly Arab. Like us. Apparently, even my pants had some secret Arab origins: “It’s pronounced Hajjar, not Haggar!” (Marwa Helal reminds me that the Egyptian dialect would say otherwise; there isn’t Arabic, but Arabics!)

The negative representations confused and vexed me, since the Arabs in our father’s family—mostly congregating around 290 Hicks Street in Brooklyn Heights—were ridiculously hospitable and overwhelmingly demonstrative. By the end of any visit, I was so stuffed with food and love and hugs that I could barely move from the couch after meals. Which was fine, since every Lebanese goodbye, as we came to call them, would take at least an hour and involve kissing and hugging and saying goodbye in at least three rooms (kitchen, living room, at the door) and one last time outside. Of course, life in an Arab household meant more than that; the attendant squabbles, judgments, and drama of every family were very much present. But the warp and weft of the fabric of human life is so entirely absent from the depictions of Arabs in America, that every representation feels instantly political and freighted with sinister meanings. The political, Deleuze and Guattari once wrote, stains every utterance. That’s unfortunate for all concerned—both Arabs and non-Arabs alike.

I can see now how the film and television and media industries was not merely reflecting popular sentiment, but also promulgating an imperial narrative—as if they’d received the message from on-high. In some strange way, they had. Related to our white supremacy problem, Orientalism involves a way of seeing the other (the Arab) that justifies an ongoing system of domination. Edward Said’s landmark analysis of the problem, Orientalism (1978), is now forty years old, and yet the phenomenon it describes feels as entrenched and normalized as it was when he wrote it. Orientalism, for Said, is the Western practice of projecting upon the East “a system of representations framed by a whole set of forces that brought the Orient into Western learning, Western consciousness, and later, Western empire.” In other words, it is a fantasy projection upon the people of the East that motivates and justifies colonial rule and imperial force. For Said, “the limitations of Orientalism are… the limitations that follow upon disregarding, essentializing, denuding the humanity of another culture, people, or geographical region.”

That’s precisely what I’d been feeling, as a teenager, as I watched the same television and movies as everyone else in my white-bread Midwest neighborhood. Instead of complex Arabs, we were treated to the repertory of Orientalist projections: images of predatory, conniving, deceitful men (sheikhs, despots, and terrorists) and passive women needing saving (belly dancers in harems with plenty of veils). The Oriental is deceitful and lying, whose word is not trustworthy, who only understands the language of force. The Orient is a place of blank and brutal deserts, without history or civilization, and it’s hiding our oil.

It’s been a century since the Orient emerged as a powerful fictive presence in the American imagination, since the end of World War I and the carving up of the Middle East into European spheres of influence (principally the British and the French). I say “carving up” because, quite literally, during the war, the secret agreement known as Sykes-Picot promised to split the spoils of war among the victors. After the war, in which Arabs fought on the side of Western forces against the Ottoman Empire, European powers drew maps, created countries, and installed Western-friendly rulers. Though the maps did acknowledge some natural geopolitical realities on the ground, others (for example, the Kurds and Palestinians) were entirely erased. Many argue that the present-day Middle East (the ongoing dispossession of Palestinians, the civil wars in Iraq and Syria, and the rise of ISIS) are the legacy of that map-carving. American foreign policy, inheriting the British role, has mostly been about oil and Israel.

Forty years later, in 2018, Edward Said’s work hasn’t been forgotten, but it’s not known well enough either; despite forty years of exegesis and new thinking around postcolonial theory and empire studies, it’s as if the machinery of empire continues to cripple our thinking about ourselves as Americans. Every time I speak to Americans, unless they are comprised of people of color, I need to presume that they’ve heard none of this, that they’ve been indoctrinated in the same ways that I was, though it could only colonize me halfway.

At the same time, much has changed. Al-Jazeera exists. Social media platforms enable everyday Arabs to share their stories and voices in a hundred ways. Arab Americans have wider prominence in the culture: not just Tony Shalhoub, but DJ Khaled and the Hadid Sisters; not just Diane Rehm and Steve Jobs, but also Linda Sarsour and Zainab Salbi. And lesser-known but more important to me, writers like Etel Adnan and Naomi Shihab Nye and Lawrence Joseph, not to mention the writers of my generation who are my friends and confidantes.

Yet, despite the widening of the general frame, Orientalism still reigns; though it’s not as brazen, its subtle forms are everywhere. Consider the opening chapter of Adam Valen Levinson’s The Fine Art of Learning to Say Nothing in Arabic, recently published by W.W. Norton and appearing at this website in November 2017. The book is part travelogue and part exploration of Arabic language, written by a Jewish American. That fact in itself is fascinating, and though the first chapter doesn’t really make much of it, I imagine that a Jewish man—who may have received an extra dose of Orientalism given that he has relatives in Israel—who comes to study Arabic is a rather interesting person. Either he aspired to understand the other or spy on him, or both; either way, he’s taken a risk and I want to know more.

I see myself in him. During the Cold War, I decided to study Russian because I simply could not believe that all Russians were evil, despite Reagan’s famous statement about the Soviet Union being “the evil empire.” I wanted to learn about this demonized people and culture, only half-aware of my own othering. I ended up, like Levinson, traveling to that land, wanting to see it for myself, and to come to my own understanding of this people.

The opening chapter, however, is so replete with Orientalisms that it halts me in my tracks, makes me not to want to follow this narrator. He, too, seemed interested in learning more about this people after the 9/11 attacks, but not necessarily as a peace mission: “The attack had made us all forcefully selfconscious. We perceived them, assumed their perceptions of us, and then canceled all the flights to Beirut. But by learning the primary language of this region, some of us thought, we might be able to figure out what they were really thinking.” It’s hard not to read this as a subtle version of the question that the media promulgated after the September 11, 2001 attacks: “Why do they hate us?” “We perceived them” and saw them as terrifying, since we canceled our flights. “What were they thinking?” is the operative idea, in both senses of the phrase—what are they thinking about, and how could they have done this to us, and made us decide to skip seeing the Paris of the Middle East?

I would have loved to hear how he personally—and not this strange white “we”—decided to make this journey into language and land, because we learn later that his cousin in the Israeli army bluntly asks him why he’s decided not to study Hebrew. All he can come up with is that everyone in Israel speaks English already. It seems too coy, since Israelis often hear Arabic as scary just by itself.

When learning about the root word for carrot, Levinson makes a joke about the strangeness of seemingly related words: “Of course, it was total coincidence in that place where linguistic bloodlines run tangled back into ancient history, but as we headed toward Jazirat al-‘Arab, I couldn’t help but imagine our destination like a great carrot on the map.” And later, the coup de grace of the piece, “And we descended and the triangle of Abu Dhabi stuck out into the water like a slice of baklava.” On the one hand, the tone here is humorous, even silly. It led to a hilarious parody on Twitter written by Laura Haugen, called “The Fine Art of Learning to Bullshit in America,” which ends: “The plane arcs toward New York, and the concrete buildings stab the sky like a handful of French fries stretching toward ketchup.” It’s preposterous, when you translate it.

In the comment stream on Lit Hub, Fatima Khansahib’s note on the baklava was equally amusing: “GREEK Baklava is triangle-shaped. Everyone knows baklava in the Middle East is either rolled or DIAMOND shaped…. But only a true orientalist would want to come to the Middle East with so much enthusiasm and would have the arrogance not to understand the complexities of what is an incredibly important cultural pastry.” Plus, we don’t call it baklava, but baklawa.

To Arabs, whose experience of imperialism and colonialism is brutal and direct, talking about their land as delectable bits of food, sweets to be consumed, can feel like more than mere caricature. It’s the way that the West has perceived the lands of the Middle East—something for our consumption. “It’s our oil, after all. It’s our Holy Land, after all.”

Learning any foreign language is always full of mystery, and so I’m willing to grant Levinson the natural fascination and eros which accompanies this relationship. Yet, Orientalist metaphors stain his description: “I was hooked long before I felt the language let fall the first of its veils, revealing morphology as finely calibrated as the engine of a race car.” And, of course, the veil. What would the Orient be without those diaphanously-erotic (or repressively-suffocating) veils?

It gets more unfortunate when it comes to Arabic language as a metaphor: “‘To live in Arabic is to live in a labyrinth of false turns and double meanings,’ Jonathan Raban wrote in Arabia Through the Looking Glass. ‘No sentence means quite what it says. Every word is potentially a talisman, conjuring the ghosts of the entire family of words from which it comes.’ Its trademark haziness can only be cleared, as far as it will ever be cleared, by knowing as many members of that family as possible.” Raban has a history of explaining the Oriental mind, but my dispute is with how he’s summoned here to describe the slipperiness of Arabic language. Language itself is the slippery thing, as Derrida and any five-year-old will demonstrate. It’s not the Arabic mind. But it’s blamed on Arabic because that’s what Orientalism does: disavows our own uncertainty and unconscious and projects it onto the other.

I hope that Levinson’s journey in his book complicates this Orientalist opening, though I don’t want to read further. I write this not out of the desire to bash a fellow writer who made an intrepid journey into Arabic and the Middle East. But how is it possible that no one—himself, his agent, his editor, anyone at Norton—could have questioned this depiction?

Most importantly, and here I want to say that this is more important than the matter of the baklava or the language, this first chapter about Arabic language and culture and places is, astonishingly, remarkably free of Arabs. There are no Arabs at all in it, as far as I can tell—only a love interest with the Slavic name of Masha. Perhaps the “pretty attendant” on the plane is Arab.

In the process, what have we Americans missed? Who are Arabs, and what are they like? Denise Levertov had a prophetic poem about the Vietnamese, written during the height of what the Vietnamese term the American War, called “What Were They Like”? There was the sense among activists that we were perpetrating a genocide of the Vietnamese. Think about it: even our lauded and beautiful memorial to the American dead of that war does not mourn the Vietnamese casualties, which outnumbered our dead at least a twenty-fold. Maybe the question should be: what are we like?

As crazy as it sounds, this is how you destroy cultures and nations, how you kill them softly. The sad fact is that we (I include myself in this, as an American) have been destroying Arab countries for a long time. I became politicized during the first Iraq War (1991). After that censored war, in which so-called “smart bombs” were heralded as the first heroes of a “surgical” war, we learned how the US and Allied bombers targeted civilian infrastructure such as water filtration facilities and the electrical grid. According to UN humanitarian reports, the consequences of bombing and sanctions led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people, often by preventable disease, due to lack of sanitary water and medicine.

But almost no Americans knew or seemed to care about what our little war had wrought, other than kicking the Vietnam syndrome and kicking Saddam’s ass. We were still cheering our Indiana Joneses and our superior weaponry, while the local fanatics fell ridiculously on their swords. In 1996, on 60 Minutes, Lesley Stahl asked then-US Ambassador to the United Nations Madeleine Albright whether the death of half a million Iraqi children [from sanctions in Iraq] was a price worth paying, Albright replied: “This is a very hard choice … but we think the price is worth it.” Can you imagine someone saying this about American children?

By the time the second Iraq War happened, in the midst of the larger War on Terror, I was ready to write about it myself. In Sand Opera, a book of poems, I investigated the traces of that war as it appeared in documents such as the Standard Operating Procedure manual of the Guantanamo Bay Prison, the testimonies of tortured Abu Ghraib prisoners, the drawings of a man captured and rendered in secret black sites. These explorations, alongside my own reflections as a young father on the homefront, listening to the war unfold on the radio with our daughters, helped me make sense of what the imperial and Orientalist narratives constantly tried to efface.

I think as well about what continues to happen in Palestine, where the dull dehumanizing grind of colonialism and slow-motion dispossession that has carried on since 1948 is now backlit by Trump’s recent declaration that the US would move its embassy to Jerusalem and call it Israel’s capital. This act was, of course, in contravention of 50 years of US and international policy to keep the status of Jerusalem as a part of the so-called peace process.

I actually want to encourage more American writers and citizens to do this work. But, as an Arab American writer, I expect the best from our brothers and sisters of the pen, of writing, and literature, to be attentive to this epistemological violence, this cutting out by caricature, by accident, or by conscious intent. I expect an attention to this great blindspot of our empire, that we stop erasing Arabs. That we listen to Arabs. That we publish Arabs and Arab Americans, rather than those who report on those “natives” over there and their wily language. That we listen to everyone—not Arabs only, of course—who is being silenced.

I am well aware that I have my own blindspots; I’ve had them pointed out to me more times than I care to admit—around gender, race, or ability. I struggle with the same issues when representing other others; working on a memoir about living in Russia makes me aware of how easy it is to exoticize the other. The larger question I want to ask here is not merely about representation, but about the power structure of American literary publishing. Why does our literary establishment rhyme so easily with the imperial project? How can we challenge and change it, and trace the distance, for example, between Ferguson and Palestine?

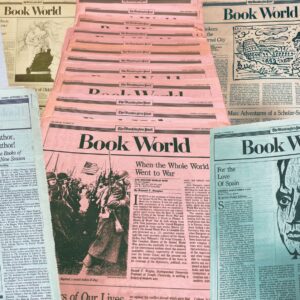

In addition to reading the classics like Edward Said and Jack Shaheen, I recommend exploring contemporary Arab and Arab American writers and scholars. There is no shortage of them, of us. For one place to start, check out the list of Arab American Book Award winners. In terms of scholarship, Evelyn Alsultany’s Arabs and Muslims in the Media: Race and Representation After 9/11 (2012) updates Said to explore how contemporary media often deploy a “good Arab” to create the illusion of complex representation, what she calls a “simplified complex representation.” In terms of literature, Khaled Mattawa’s lyrical poems and translations have brought into English so much beauty and wisdom. Likewise the work of the indefatigable Marilyn Hacker, in her poems and translations. Marcia Lynx Qualey’s blog called Arabic Literature in English provides a constant reading list. Interlink Books deserves special mention, and there are at least three literary magazines devoted to Arab literature: Mizna, Banipal, and Sukoon. For me, the existence of RAWI (the Radius of Arab American Writers) has made me feel a little more at home in the world, and at home in myself. RAWI is home to many prominent Arab American writers, including a core group with whom I regularly group-text: Hayan Charara, Marwa Helal, Randa Jarrar, Fady Joudah, Farid Matuk, Deema Shehabi.

In poetry, Hayan Charara is the master of dread, whose poems tip the earth beneath us, sliding into the unspeakable; on text, he shares goofy photos of his kids, usually dressed up in hilarious outfits. In poetry, Marwa Helal invented a new kind of poem, the Arabic, which reads right to left; on text, she’s the one who hearts us most, and keeps us hip to slang and people like DJ Khaled, whose embrace of the good life is equal parts hip hop and Arab. In her essays, stories, and Tweets, Jarrar’s drawn to the funny and provocative; one troll called her novel “a handbook on masturbation.” In group-text, she alternates between hilarity and sweetness. Fady Joudah’s just another award-winning poet and translator, whose surprising response to the Levinson affair and other grotesqueries, “Say It: I’m Arab and Beautiful,” ought to be read by everyone, vibrating as it is with the birth-pangs of something new. Farid Matuk’s baby girl pops up in group-text, as she does in his new and highly experimental poems, when he’s not going high-theory in voluminous and impeccable texts. Deema Shehabi’s two boys, and her kindness, radiating always, rhymes with her jasmine-scented and fierce poems. What does it mean to know her grandfather was once the mayor of Gaza?

That’s our little group-text, rife with photos of ourselves and our families, and notes about everything—from the theoretical and political to the mundane. They aren’t the only Arabs you should be reading, but they’re among my closest friends. If any of us is wielding a scimitar, it’s as a joke. We’re working on a collective essay called “Dispatches from the Land of Erasure”—stay tuned for that. We don’t always agree, but we listen to each other, and don’t have to explain everything from the beginning. Every few days, they remind me that I’m human, and that I’m not alone. We’re human, each little text proclaims, and we are Arab, and we are not alone.

Philip Metres

Philip Metres is the author of Ochre & Rust: New Selected Poems of Sergey Gandlevsky (2023), Shrapnel Maps (2020), The Sound of Listening (2018), Sand Opera (2015), and other books. His work has garnered fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, Lannan Foundation, NEA, and the Ohio Arts Council. He has received the Hunt Prize, the Adrienne Rich Award, three Arab American Book Awards, the Lyric Poetry Prize, and the Cleveland Arts Prize. He is professor of English and director of the Peace, Justice, and Human Rights program at John Carroll University, and Core Faculty at Vermont College of Fine Arts.