Sally Mann on the Crushing, Lifelong Reality of Artistic Rejection

“Just my life’s work there that you’re tossing around like scrap paper.”

Once I decided, at the age of seventeen, that I would try to make a career as an artist, it took me almost no time at all to realize how miserable it was going to be. I had just mastered the ironic tilt of my Left Bank beret and the requisite squint of the eyes—helped along by the smoke from the unfiltered cigarette depending in a Bogartian dangle from my sullen lip— when I wrote this in my journal:

Already!

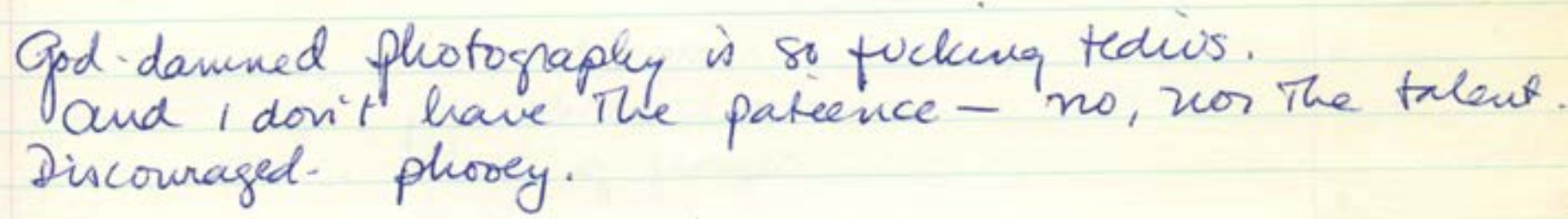

Ready to quit at seventeen, before I’d even started. My first roll of film and I’m wondering if maybe I should look into something else . . . less “tedius,” less demanding, more paint-slinging and pirouette-y and unrestrained. Not so many rules and formulas. And here is the word that you will never, not another time in this book, see again: talent—something I believed in back then. And, as I wrote, I for sure believed I didn’t have it.

What I was wrong about was the patience part. Patience, it turns out, can be learned, and over a long period of time I have learned it. Patience, in conjunction with its sibling, tenacity, can take the place of . . . that other thing. So, not only can it, in its own deliberate way, shape-shift into the spark and vitality and intuition and physical form of Art, but where patience really saves your artistic bacon is in helping you over-come suffering.

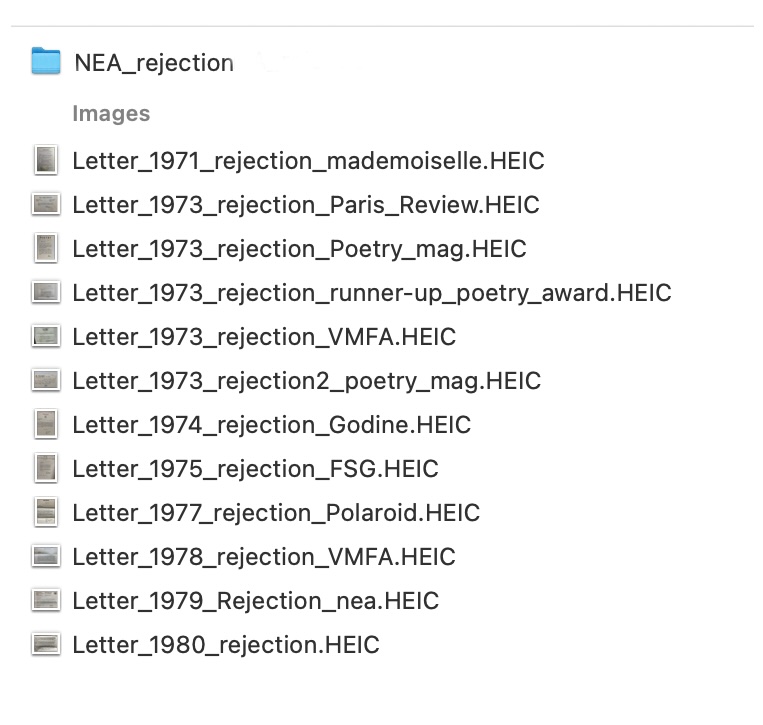

There are a lot of ways you will suffer. Mostly you will experience rejection. This is just a quick screenshot of some of the rejection letters that I saved, but countless others were so humiliating and depressing that I balled them up and threw them away (you will note that the National Endowment for the Arts merits its own folder because there are so many rejection letters).

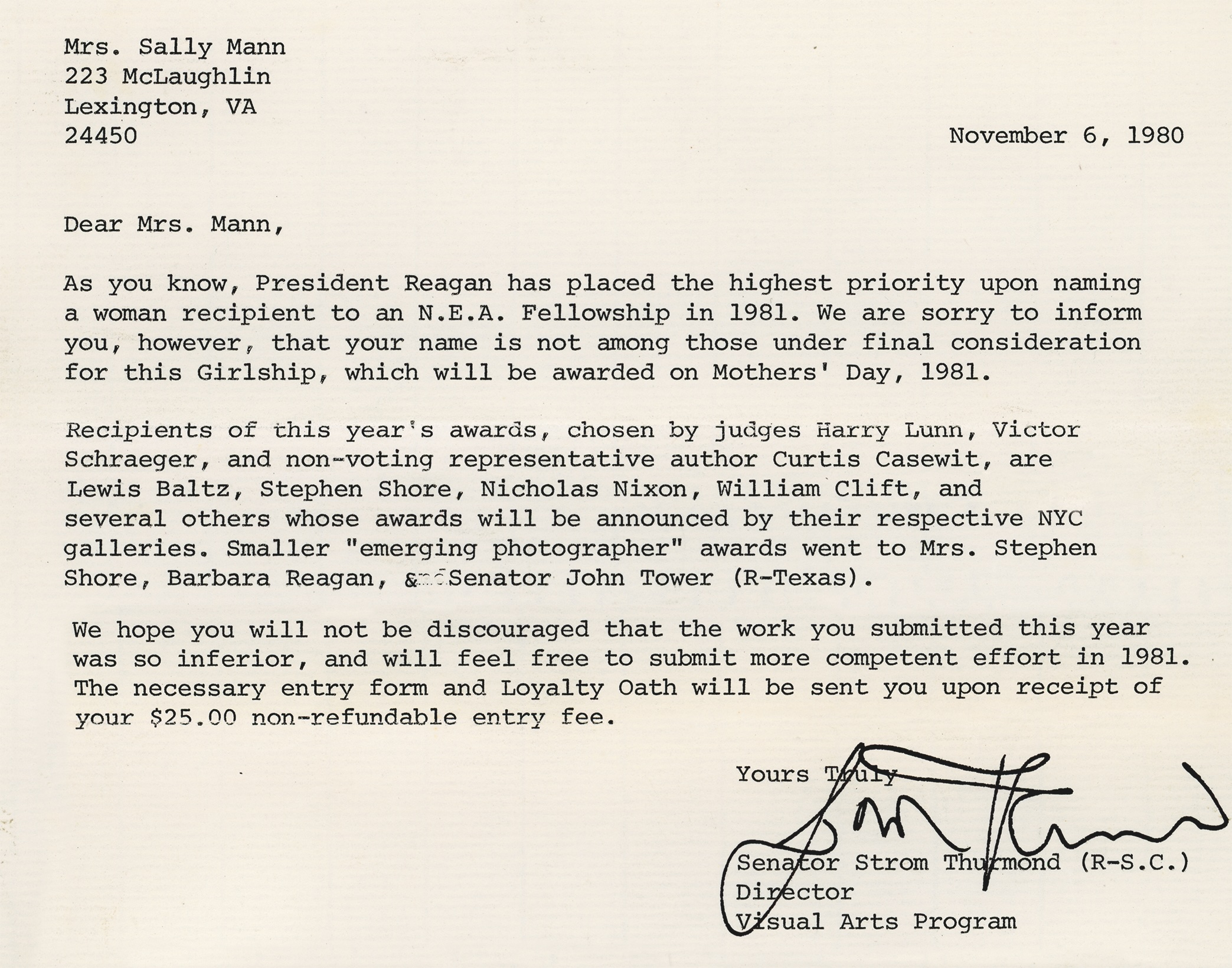

In fact, rejection letters became so commonplace that Ted sent me this all-too-true spoof:

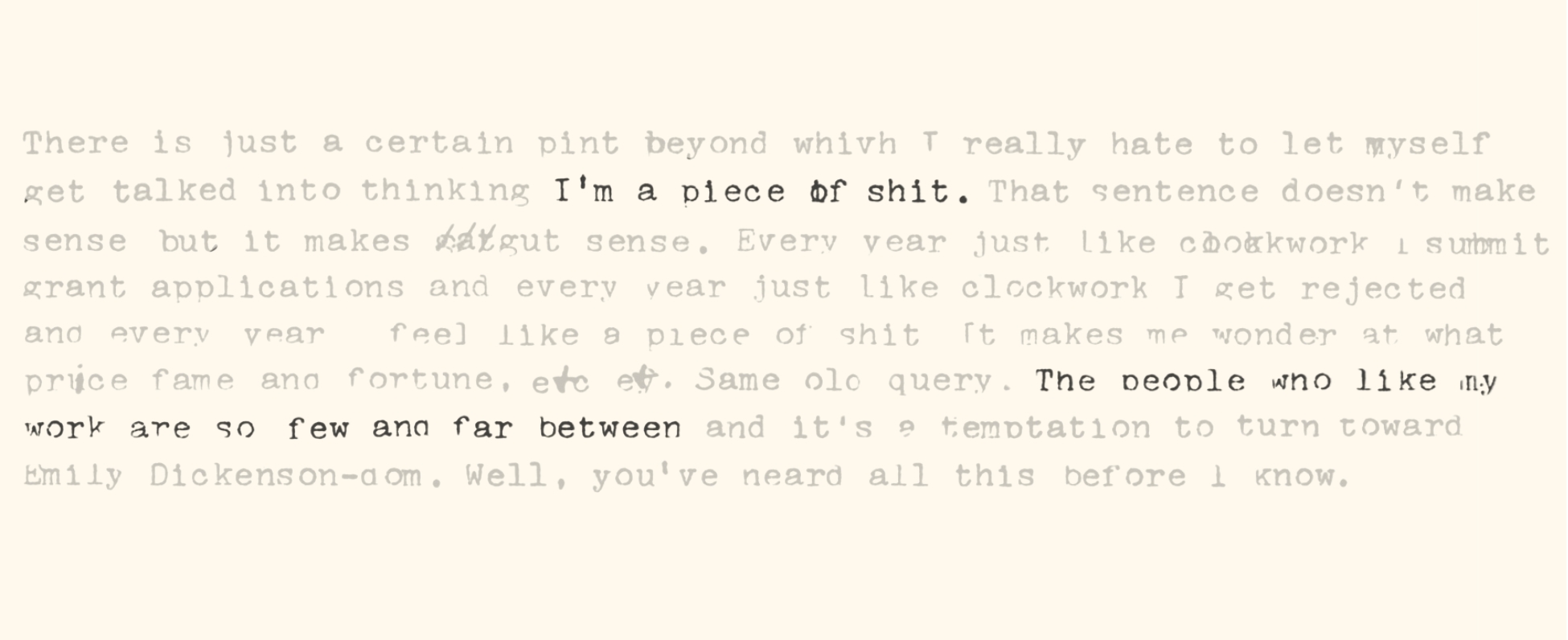

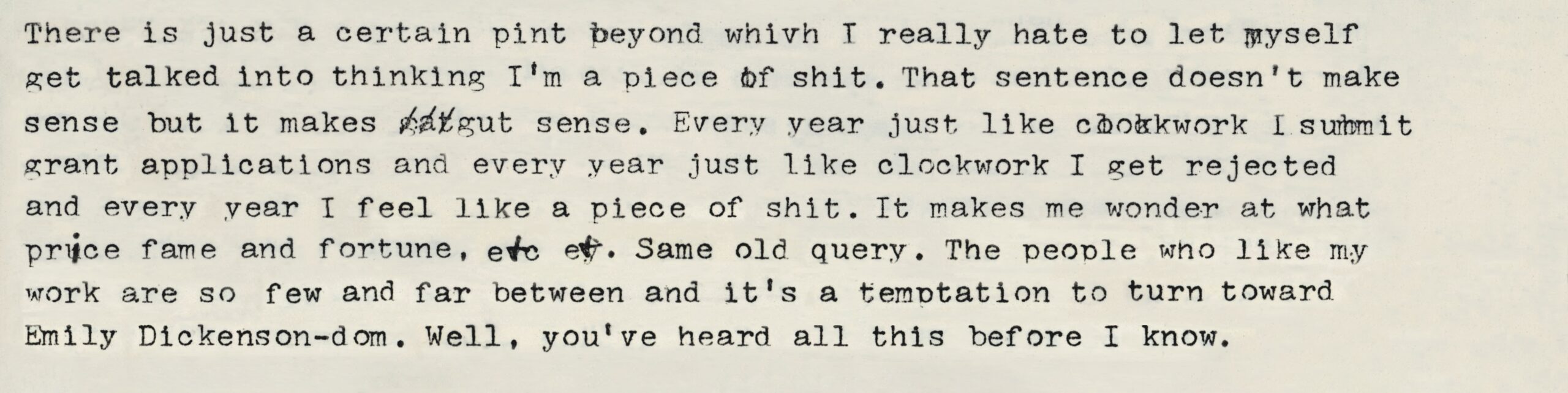

Rejection came in all forms. And why on earth am I writing that in the past tense? I am still getting rejections; my work has been turned down flat several times by curators in the last few years. Rejections still hurt, just like they always did. I felt like a piece of shit in 1977 when I wrote this to Ted:

And in the end, that’s just what I did. “Emily Dickenson-dom,” or close to it, embracing the sentiment I once heard from my friend John Dickerson: “To be great, you have to disappear.” Disappearing made me less vulnerable (if not great). I don’t know if I’m unique in this—probably I am especially thin-skinned—but I can conjure up old slights with an elephantine recall, while being unable to even faintly discern the outlines of a compliment. But just in case some of the details escape me forty years later, like exactly what kind of sandwich a certain gallerist was eating as he fingered through my prints (Reuben), or what he was wearing (pink plastic belt and matching shoes), my contemporaneous letters from the time, written most often to Ted, bring them immaculately and vividly back to mind.

One from the spring of 1977 is excruciating in its details of my humiliation at the hands of a gallerist at what was then the most important photography gallery in New York. It’s typed with such pounding despair and fury that certain letters of the alphabet actually tear through the paper (this was an old, manual typewriter). In case poor Ted did not know I was upset, on every third line, words like “ultimate degradation” and “utter speechlessness” and “brazen heel” appear in ALL CAPS.

The story isn’t just a simple gallery rejection; I’ve had plenty of those, some more memorable than others. One of the more memorable was being shown out of a gallery clutching prints from my early Family Pictures (Damaged Child, The Last Time Emmett Modeled Nude, Jessie at 5, etc.) with the words “You’ll never get anywhere with those; way too domestic” ringing in my ears.

No, this letter to Ted recounted a rejection with an extra twist of the knife, O. Henry territory. Funny, if you have a sense of humor bordering on the cruel.

It began with a box. A gorgeously undulating, custom-made portfolio, each wood in its striped pattern a different color: pale maple, warm walnut, ruddy cherry; wood cut and hewn from our own woods at the farm. It was lined with a dark green velvet. I had traded several of my rare—even then—platinum prints to have it made and I was convinced that the reverence-inspiring container would set the tone for viewing the work inside.

But the problem was, it was heavy. Really heavy. And pretty big. And it had no handle. But that did not stop me from deciding to carry my work up to New York on the train in this splendid vessel.

I have no way, even today, of cranking down the waterworks tap and I began to cry noisily, wiping my nose on my forearm, so blinded by the tears that I could hardly see to gather up the prints.

This was to be my second, confirmatory trip to the gallery. The first time I had gone, the director, nameless here but mud on my lips for decades after, viewed my work with much admiration, even without the awe-inspiring box, and proposed a show later in the year. But, just one thing: He wanted me to bring examples of new work back to him in exactly three months.

As unlikely as this sounds, I had an acquaintance who also had taken his work to that same gallery a week before me, and had an almost identical experience, right down to the “come back in exactly three months” directive. We were delighted and wondered if our shows would be at the same time, although the director was unaware that we knew each other.

As instructed, after three months, my friend made an appointment to show his new work, and I waited to hear from him the dates of his, or our, show. Instead, what I heard was a tale of dejection and confusion. When he had shown the new work, the director had leaned back in his chair, stroking his chin, and quizzically, haltingly, said, “You know, this is so odd; the things I liked about your work before are the very things I don’t like about it now.” My friend repeated that sentence to me three times, each time with more mystification and pain. He simply couldn’t accept the unreasonableness of this reversal and the confusing, contradictory wording.

I did my best to console him, all the while having the, yes, I know, selfish thought that maybe without him I’d get the whole gallery now! I bought my train ticket for the next week, exactly three months, and set off at dawn with my box, so much heavier now that it was full of mounted prints. Almost as heavy as I was, or so the train conductor quipped as he hoisted it up the stairs for me. From Penn Station I somehow muscled the box and my little cardboard suitcase onto an uptown bus and went straight to my appointment at the gallery.

In the letter to Ted I describe my confidence, writing: “I breezed in feeling like a million dollars”—however unlikely it was that anyone was breezing anywhere with that box in their arms—and commenting on how good-looking the director was, how warm his smile. With great ceremony, I opened the box and he began flipping through the prints, pulling out every third one, stacking them unevenly to the side. I tried to disguise my concern at their treatment as casual indifference: Oh, ho hum. Just my life’s work there that you’re tossing around like scrap paper. But I consoled myself with the thought that obviously he didn’t need to study each image with the reverential care I was expecting, since this was just a confirmation of his first impressions from three months ago and he was probably making a preliminary edit for the show.

When he was finished, there was a pause, and he sat down in his chair as I held my breath and mentally turned the pages of the calendar to showtime. He leaned back. He stroked his chin, his forehead creased with perplexity and distress, and he said:

Well, you know exactly what he said, don’t you? It was the very words, the exact same fucking words.

My letter to Ted reports “a flush that went from head to toe and utter, UTTER speechlessness. A look of near-tearful agony on my face.” It was not near-tearful for long. I have no way, even today, of cranking down the waterworks tap and I began to cry noisily, wiping my nose on my forearm, so blinded by the tears that I could hardly see to gather up the prints. Patting them into a roughly even stack, I turned them sideways to tap them like a sheaf of irregular term papers, but they were debossed platinum prints and would not conform. I was sobbing by then, and the office staff was peering around the doorway as I crammed the prints unevenly into the box and crushed the top down on them, their edges sticking out from three sides, some folded, one blocking the latch.

The director was pounding on the elevator down button when I finally scooped up the box with both arms, and the concerned-looking staff, one of whom was my (now) good friend Maude, pressed a Kleenex on me, and stuffed the rest of my belongings into the elevator with me. When I got to the ground floor, I sat on a bench and restacked my prints into the box. Almost all of them were damaged. I had spent every hour of the past three months printing those platinum prints under a blistering sunlamp, debossing the deckle-edged BFK paper that had to be special-ordered from Europe, soaking the sheets of precious paper, running them through the etching press at the university after hours, layering them in drying cloths, dry-mounting the delicate platinum prints onto the now-debossed paper, and then signing in light pencil. Like a real artist.

I went out on Fifth Avenue, where the buses went the right direction to take me down to my friend Robbie Goolrick’s fifth-floor walk-up (the ground floor a Spanish restaurant, then two floors of Chinese brothels, he reminded me yesterday) on what had to be the noisiest street in New York, Thirty-Fifth. I waited at the curb until the right bus came and gathered together my purse, my sweater, my suitcase, and the box. No helpful conductor this time.

I rejiggered my belongings and hoisted the box up onto the stairs, followed by the rinky-dink suitcase. As I began to reach for the chrome bar to pull myself up, the doors wheezed shut. I jammed my fingers in the rubbery lips and tried to pry them apart, running beside the bus. No go. The bus picked up speed. I ran, losing my flip flops. Kept running, barefoot, as the bus picked up speed. As I frantically maintained contact with the side of the bus, I envisioned my ignominious death under the wheels, and the even more ignominious tossing of the box and its contents into the trash. And, fine, I thought. That’s probably where the hell you belong.

__________________________

Excerpted from the new book Art Work: On the Creative Life by Sally Mann. © 2025 Sally Mann. Used with permission of the publisher, Abrams Press.

Sally Mann

Sally Mann is a Guggenheim Fellow and three-time recipient of the National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship. She was named “America’s Best Photographer” by Time in 2001. In 2021, she received the Prix Pictet and was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame. She has been the subject of two documentaries: Blood Ties (1994), which was nominated for an Academy Award, and What Remains (2006), which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival and was nominated for an Emmy for Best Documentary. Mann’s Hold Still: A Memoir with Photographs (Little, Brown, 2015) received universal critical acclaim, was a finalist for the National Book Award, and won the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Nonfiction. Mann is based in Lexington, Virginia.