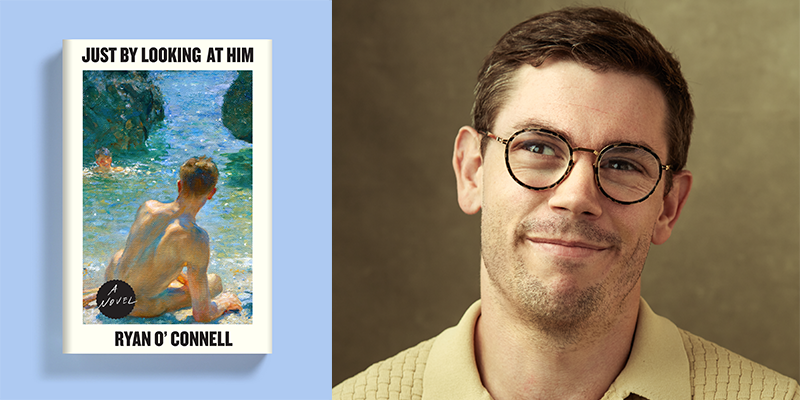

Ryan O’Connell on the Importance of Facing Rejection in the Sack and Finding His Voice in Hollywood

Greg Marshall Talks to the Star of Netflix's Special, aka the “Gay, Disabled Nancy Meyers”

Ryan O’Connell was four episodes into filming the final season of his Emmy-nominated Netflix series Special when the world shut down because of Covid-19. Instead of giving into despair he focused his creative energies on what would become his vibrant debut novel, Just by Looking at Him, which follows the travails of Elliott, who, like O’Connell, is a thirty-something TV writer with cerebral palsy.

Despite his professional success slinging jokes for a hit sitcom, Elliott feels trapped in a boozy, co-dependent relationship with his long-time boyfriend, besotted with pricey “natural” wines and numbed by hours of TV every night.

When Elliott’s abrasive, fancy-gay boss shares a story at the office about hooking up with a sex worker, Elliott decides to seek him out without telling his boyfriend.

Like O’Connell, I’m a gay man with mild cerebral palsy. As with O’Connell’s earlier work—a dishy, exuberant 2015 memoir and, of course, his groundbreaking, loosely-autobiographical TV show—I found myself chortling with recognition and, let’s be honest, crying a little at seeing a version of my life on the page.

Especially since we’re both millennials, O’Connell’s work, however singular and auteurish, has always felt like someone raided my closet, and my psyche, and put on a play: there are my sturdy, dad-like Tevas at the pool party.

Seeing O’Connell’s boyishly handsome yet strapping character on Special, also named Ryan, lose his virginity, socks and glasses still on, looking like he’s about to be shot out of a circus cannon, I remember making the kind of empathetic, horndog observation good TV demands of us. “Damn, Ryan is sexy. Wait, am I sexy?!”

We only see Ryan composing at his computer a couple of times in the series, though it may be these glimpses of self-creation I relate to the most, fingers pecking at keyboard, already feeling that mix of shame and pride that comes from telling all about your body.

O’Connell’s work, in other words, gave me a renewed sense of control over my own. Watching him, I found agency in my body’s many quirks I had forgotten was there.

It was remarkable to see a person with CP use what made him different all his life to make art, jokes, and money. I liked to imagine the action onscreen choreographed in capital letters in Final Draft Courier: Ryan WIGGLES into pants. He PUTS ON shoes. It’s not that our CP manifests itself in the exact same way—no man’s brain damage at birth is identical to another’s—as much as it is our shared craft that made me feel emboldened, each constricted move rendered on the page with intention.

O’Connell’s work, in other words, gave me a renewed sense of control over my own. Watching him, I found agency in my body’s many quirks I had forgotten was there.

The pleasures of Just by Looking at Him are no less sidesplitting, seductive, or daring than anything in Special. I found my leg tense with fellow feeling, or a spastic kind of schadenfreude, when Elliott is forced, through a comedy of errors equal parts Shakespearean and Seinfeldian, to watch the sex worker he’s been seeing on the sly expertly top his boyfriend, who lets out “guttural, almost inhumane, moans of pure pleasure” Elliott has never heard before. “Watching them move together with such cohesion and fuck in positions I could never force my body into was gut-wrenching,” Elliott observes. “This was the way sex was supposed to be. This was sex without me.”

The novel is full of deft observations that only a writer with CP could make: the agony of trying to appear nonchalant when you are on your knees helping give a dog a bath, the need to steady yourself against the toilet to get out of the bathtub or lean a little to hug, the idle suspicion that possessing a “giant ass” is a CP thing (yup, it is!).

About halfway through the novel, as Elliott’s world is starting to implode, he bemoans the lack of other disabled people in his life. Rehabbing a hamstring torn during a drunken escapade, Elliott runs into an acquaintance from his physical therapy days as a kid. In time, the two strike up a friendship. “I look at Jonas, wanting to tell him everything, because if anyone would understand, it would be him, wouldn’t it?” Elliott confides to us. “I mean, I don’t know a lick about his life but both having mild cases of cerebral palsy, there’s a shared experience there. A Cliffs Notes to your misery.”

Your misery, yes, but also your joy. And mine.

My conversation with O’Connell has been editing for clarity and concision.

*

Greg Marshall: You craft sex scenes that are wickedly funny, touching, and revealing. What do you think it is about sex that’s so useful from a storytelling perspective?

Ryan O’Connell: Sex says a lot. I think that being disabled, I felt castrated at birth, for sure. And I feel like, you know, my whole life’s mission is getting my dick back. The need to be objectified and seen as just a body is so powerful. And it’s something I still feel to this day that I need to wrestle with or whatever. To be seen as just a body would be the greatest honor and privilege of my life.

I obviously face no judgment from my partner, but there’s always this nagging suspicion that I’m not good enough in bed, or I’m not able to meet him where he is. That inadequacy is always lurking. It doesn’t take center stage at all or prevent me from having an incredible relationship, thankfully, but I think it’s always just sort of there.

GM: That desire to be objectified by a stranger may be what makes Elliott go outside his monogamous relationship with a sex worker in the first place, no?

RO: Elliott’s worst fear is being rejected for his body. He pays someone whose job it is to accept him warts and all. And that becomes a very safe place for him to explore without fear of rejection. But what starts out as empowering and as exciting becomes limiting when he has these delusional fantasies of River [the sex worker] suddenly wanting to fuck him for free. What starts as a safeguard against rejection becomes the embodiment of rejection.

GM: What’s so interesting about Elliott’s journey is that rejection propels him toward a less self-destructive lifestyle.

RO: Being rejected, putting yourself out there and being vulnerable and bouncing back from that and not letting it be an indictment of your worthiness or your value as a person is incredibly powerful, and a lesson that everyone should learn, disabled or not.

I felt like I needed to make my own base rather than be a company man or a writer for hire. But it was really frustrating because Hollywood is so spineless and fear-driven. They need reference points for what you’re doing and there just wasn’t any of that for me.

GM: What was it like trying to break into Hollywood in the early 2010s when there were so few gay, disabled writers and performers?

RO: When I started writing for TV in Hollywood, people really didn’t know what to do with me. I was this weird kind of diverse they couldn’t profit off of or monetize [laughs]. I knew very quickly that my voice, for better for worse, is very specific. A lot of gifted writers can mask it and write for a show about doctors or write for a show about whatever and really acclimate to the tone of a show. I realized that I could not do that. I felt like I needed to make my own base rather than be a company man or a writer for hire. But it was really frustrating because Hollywood is so spineless and fear-driven. They need reference points for what you’re doing and there just wasn’t any of that for me.

GM: You’ve created some of those reference points in the culture with your memoir and Netflix show. I’ve seen what it’s like being able to reference your work while pitching my book. It made a huge difference.

RO: That means a lot to hear that. It’s great that there’s a reference now, there’s Special, and people can point to it and be like, “Oh, your project is like this. I understand.”

GM: Have we made progress on the disability front? Where do you feel we are now versus when you sold your memoir?

RO: We haven’t made nearly enough progress. I think when I compare it to the progress of other marginalized identities and how conversations have deepened around gender, race, sexual identity, I think disability comes up short. And that is a really frustrating thing. We live in a profoundly ableist society. It’s almost like carbon monoxide. You’re not even sure you’re breathing it in and it’s slowly poisoning you.

I mean, I’m an activist in the sense that I’m a gay, disabled male who walks around with the confidence of, like, Rob Schneider in the late nineties.

GM: Why haven’t we made more progress when it comes to disability?

RO: Disability is profoundly uncomfortable given the value systems of our culture. We live in a culture that is about productivity. It’s about being bigger, faster, stronger. Also, it’s tied into aging. We don’t know how to deal with mortality. If you live long enough, odds are you will end up disabled in some form. People don’t want to deal with that. There’s a sort of safety in advocating for an identity that you could never inhabit.

GM: You’re sometimes called an activist. Are you an activist?

RO: I’m really, really not. I mean, I’m an activist in the sense that I’m a gay, disabled male who walks around with the confidence of, like, Rob Schneider in the late nineties. That is, I guess, its own form of activism. But I’m not out here signing petitions. I just do my work. That’s where I focus all my emotional labor: telling queer, disabled stories. But I find the response from the disabled community has been so overwhelmingly positive. And I really am grateful for that because I know as marginalized people it’s easy for us to eat our own.

GM: With so few disabled, queer creators in the spotlight, there’s bound to be outsized pressure on your work.

RO: I feel some sort of guilt sometimes that I’m not doing enough. Am I doing it correctly? Am I doing everything I need to be doing? It’s a lot to take in. And it’s also like, I’m not Ryan Murphy. I don’t occupy this insane space of privilege and power either.

Don’t be mad at the marginalized person that is telling a story that doesn’t reflect your own lived experience. Be mad at the people who are greenlighting TV shows and films for thinking there can only be one.

GM: And it’s not like any one person’s story can encapsulate the entire experience of a community.

RO: There can be a kind of misdirected anger where it’s like: Don’t be mad at the marginalized person that is telling a story that doesn’t reflect your own lived experience. Be mad at the people who are greenlighting TV shows and films for thinking there can only be one.

GM: At one point in the novel, Elliott makes a list of all the disabled people he knows. The point of the exercise, in his case, is that he doesn’t know very many disabled people. I wonder: were you around many disabled people growing up?

RO: My parents were very upfront about what I had, but their whole thing with me was like, “You are ‘normal.’ Your case is mild. You don’t have to be hanging out with disabled people.” I feel like I lived a double life because, as you know, when you’re a child, CP is the star. There are so many surgeries, and there’s so much physical therapy, and there’s so much maintenance. I would go to school and I’d be the only disabled person and then I would go to physical therapy where I was in a sea of disabled people. I was usually the most high-functioning there. And then I felt very uncomfortable because of internalized ableism.

GM: I relate to all that hardcore.

RO: This is very forward-thinking and very 2022, so no blame on my parents, but I wish they had made a concentrated effort to surround me with disabled people in a positive way when I was younger because I did not have disabled friends at all. And, in fact, I resisted it. I just felt like my identities were so disparate. It created a lot of damage for me because I didn’t feel disabled enough to be with disabled people. I didn’t want to be with disabled people. But I was never able-bodied enough to be with the able-bodied kids. So I really existed in this bizarre limbo where I didn’t fit in anywhere.

I try to write things that are not all to do with the trauma of our marginalization.

GM: Toward the end of the novel, Elliott asks, “Where does my cerebral palsy end and my learned helplessness begin?” It’s a question I grapple with as a person with CP. Did writing the book help you answer this question for yourself?

RO: Nope! [laughs] The funny thing about writing about this stuff is it’s no magic trick. You definitely take away some of the power of your fear and remove some of the pain but the lessons Elliott had to learn, I’m just now getting into some of them myself.

GM: Can you talk about the importance of humor when addressing heavy topics?

RO: I try to write things that are not all to do with the trauma of our marginalization. I don’t know. It’s complicated. I feel like in a lot of the queer fiction and nonfiction I read, there’s still an emphasis on our pain and our trauma and it’s not funny. I read funny things as a funny person. That’s really what I gravitate towards. And I feel almost like if you’re funny, it’s seen as a detriment. I got this review on Goodreads (which of course I don’t read, what are you talking about?) and it was was like, “This is a book that rich white ladies have been able to write for a long time, except it’s told from a queer, disabled point of view.” And to me, that’s the highest compliment. If I can be the gay, disabled Nancy Meyers, chic.

*

Ryan O’Connell’s debut novel, Just by Looking at Him, will be available June 7 from Atria Books. He is also one of the stars of Peacock’s Queer as Folk, which debuts June 9.

Greg Marshall is the author of the forthcoming memoir Leg: The Story of a Limb and the Boy Who Grew from It (Abrams Press, June 2023). He is a National Endowment for the Arts Fellow in Prose and a graduate of the Michener Center for Writers. Find him on Twitter @gregrmarshall.

_______________________________

Just by Looking at Him by Ryan O’Connell is available from Simon & Schuster

Greg Marshall

Greg Marshall was raised in Salt Lake City, Utah. A National Endowment for the Arts Fellow in Prose, Marshall is a graduate of the Michener Center for Writers. His work has appeared in The Best American Essays and been supported by MacDowell and the Corporation of Yaddo. Leg is his first book.