Ruth Madievsky on the Semi-Cursed Nightlife of Los Angeles

In Conversation with Maris Kreizman on The Maris Review Podcast

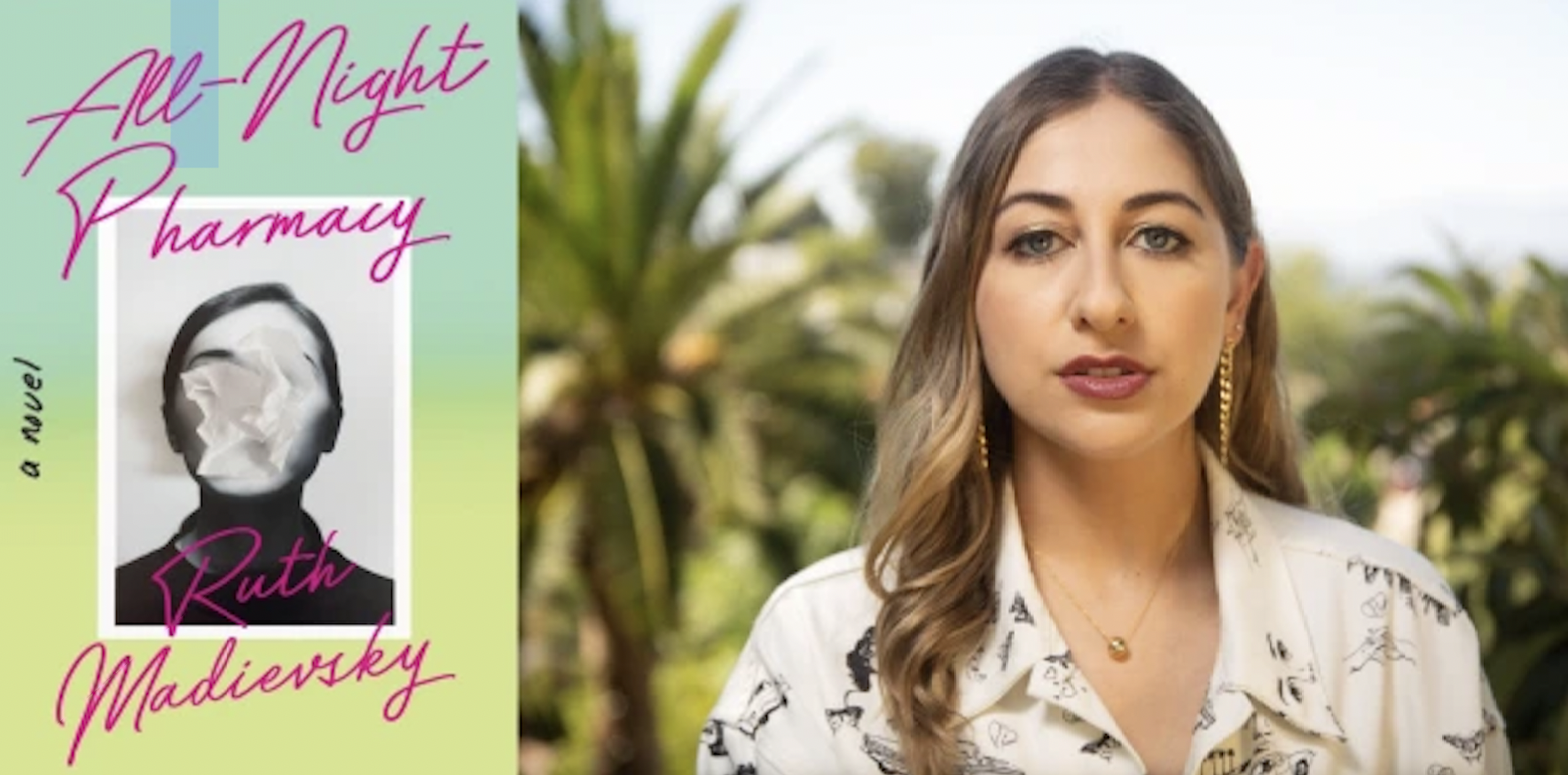

This week on The Maris Review, Ruth Madievsky joins Maris Kreizman to discuss All Night Pharmacy, out now from Catapult.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts.

*

from the episode:

Maris Kreizman: [The bar] Salvation has a really, really specific vibe in this book and I’m wondering if you could tell me how you conceived of the place, what it looks like, what it smells like, all of that.

Ruth Madievsky: Yeah. Have you spent much time in LA before, Maris?

MK: Yes.

RM: So you know LA has no shortage of semi-cursed nightlife, where it’s like you go to a bar or a club and there’s parts of it that are like, oh, I love that chandelier! Oh, this is an amazing Pisco Sour. But then it’s like, why is that dog groomer feeding that obviously 15-year-old kid mouthwash? There’s just always something weird going on. I wanted to create this bar that was sort of like a refuge for these fuck-ups.

They know there’s something incurably wrong with them, but they’re here because they do not wanna know what that thing is. It’s sort of a place where they can all be family under one roof where it’s almost outside of regular society, like weird things are always going down. I just picture it as like, the floors are always sticky. People are always hooking up with the wrong people in the bathroom. I had this throwaway line that I ended up getting rid of where the narrator hooks up with some guy in the bathroom and cuts her lip on his Star of David necklace.

MK: A nice Jewish boy.

RM: A nice Jewish boy, kind of. And there’s a scene in the book where someone is feeding a goat a beer, and then the goat starts making this horrible sound like a penny in a blender, and then that kinda ends quickly. So yeah, I haven’t been to that bar specifically, but I imagine it as sort of an amalgam of different dives where all these people who are trying to fake it till they make it, while knowing they will actually never make it, find refuge in each other’s company, under the eyes of an apathetic God.

MK: And of course when we are taken along with the narrator to Salvation, it’s because her older sister, Debbie, has dressed her up and it seems like they’ll have a fun girl’s night out. And then suddenly we realized that that’s not the vibe we’re gonna get here.

RM: Yeah, and I think the narrator keeps agreeing to go out with her chaotic, dominating older sister in the hopes that maybe this is the time it’ll just be a fun girl’s night out. Maybe we can be what quote unquote sisters are supposed to be. Like my older sister can kind of shepherd me through this life in a way that doesn’t make me feel like a black hole the next day. She just never really gets that with her sister, but just can’t find herself cutting her loose.

MK: There’s a line where the narrator says, being Debbie’s sister was obliterating, which was also the closest thing to knowing who I was.

RM: Yeah, that’s the exact line.

MK: That really sums it up. It feels really familiar to me that we often have someone who is just so larger than life that you’re just kind of along for the ride.

RM: Yeah. You know that it’s toxic and it might end with you maybe dead or severely traumatized, but it’s kind of like, what would my life be without this person? It’s a little terrifying to imagine it. One thing I realized late in the book is that, well, I don’t need to have a pithy thesis of the relationship between the Holocaust and why these characters are the way they are. It does feel like there is a relationship between the narrator and her sister losing relatives to the Holocaust and to Soviet terror and her inability to become estranged from her sister.

I think there’s this sense that we don’t just cut off our living relatives, even if they’re horrible. And I think a lot of immigrants probably understand that to some degree. And a lot of Jewish people probably understand that to some degree this hope that even if things are toxic, you can’t give up on that person and that maybe things will get better eventually. And even if they don’t, that’s not the point of family.

MK: Right. They’re here to torture you if that’s what they’re here to do. And of course you show that so beautifully when we meet Debbie and the narrator’s mother and their grandmother. A manifestation of some of that trauma is that their mother is incredibly paranoid. And the narrator might be too.

RM: Yeah, her mom grew up in America, but inherited all this family lore about her grandfather being murdered as an enemy of the state. And the aunts and uncles that perished in Babi Yar. She has this paranoia that any day now things in the US could turn and she needs to be ready to go at any time because the fire squad could be around the corner whenever, and it really makes her incapable of functioning in society.

The narrator is kind of terrified by this combination of her mental illnesses. Terrified that they’re coming for her too. That they’re in her genes. On the one hand, enabling her mom is what helps her survive, because you can’t really help someone see reality if they’re not willing to to some degree. But she also understands that enabling her is toxic in its own way and ends up with her spending more time with those illusions herself, wondering what her place is in digesting all this trauma around her that she didn’t personally experience.

MK: Absolutely. It’s described at one point that the grandmother thinks of the mother’s disability as a betrayal, because of course she was brought to this land of opportunity.

RM: Just from talking to a lot of my friends who are also immigrants or children of immigrants, I think that there’s that very real sense of, why do you need a therapist? And like embarrassment, like, why are we on SSRIs? Why do we take benzos? We weren’t the ones who saw our father get shot. We weren’t the ones who feared for our lives every day and were never allowed to go to a synagogue.

And if we had been queer and the Soviet Union would’ve just not had any life at all, and yet why do we seek out this help? And I think part of it is just that we’re willing to do it. Whereas, you know, those older generations I’m sure could really, really benefit from it. But I think there is that kind of generational divide sometimes, like, why do you need so much help? Like, we’re fine.

MK: Yeah, when it’s truly a matter of survival, there’s no time for therapy.

RM: Like was there Lexapro in Soviet-era Moldova? I doubt it.

*

Recommended Reading:

The Men Can’t Be Saved by Ben Purkert • Not Here by Hieu Minh Nguye

__________________________________

Ruth Madievsky’s debut novel, All-Night Pharmacy, is out now from Catapult. She is also the author of a poetry collection, Emergency Brake (Tavern Books, 2016). Her writing has appeared in The Los Angeles Times, Harper’s Bazaar, Guernica, Kenyon Review, and elsewhere. She is a founding member of the Cheburashka Collective, a community of women and nonbinary writers whose identity has been shaped by immigration from the Soviet Union to the U.S. Originally from Moldova, she lives in L.A., where she works as an HIV and primary care pharmacist. @ruthmadievsky. www.ruthmadievsky.com

The Maris Review

A casual yet intimate weekly conversation with some of the most masterful writers of today, The Maris Review delves deep into a guest’s most recent work and highlights the works of other authors they love.