5 Book Reviews You Need to Read This Week

“Most of us don’t mind literary grave robbing, especially when it comes to authors we love.”

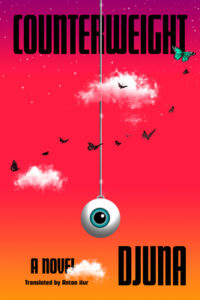

Our feast of fabulous reviews this week includes Peter C. Baker on Nicole Flattery’s Nothing Special, Joyce Carol Oates on Ursula Parrott’s The Ex-Wife, Lauren LeBlanc on Tessa Hadley’s After the Funeral, Hari Kunzru on Djuna’s Counterweight, and Casey Cep on Tennessee Williams’ The Caterpillar Dogs.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s “Rotten Tomatoes for books.”

*

“This description, I’m aware, might call to mind a certain mode of historical fiction that feels awkwardly stuck between narrative art and Wikipedia—the kind of novel where you feel the author’s presence as a tour guide, always nervously looking over their shoulder, dropping more period detail and context to make sure you’re learning what you’ve come to learn. Nothing Special is nothing like that … Flattery manages to cannily anatomize the famous artist’s powers and appeal while simultaneously pushing the man himself almost entirely out of the frame. It’s a method that the book uses more than once—sneaking up on its subjects from odd angles, as if distrustful of more direct paths …

In Flattery’s first book, the prose sometimes seemed so intent on preëmptively repelling false hopes or unearned optimism that it functioned not just as armor but also as a straitjacket, limiting the registers of feeling the stories we’re able to access. Nothing Special is a richer, more flexible undertaking … Just as Nothing Special is a great book about Warhol with almost no Andy Warhol in it, so too is it a sneakily moving homage to human kindness, where kindness appears only in quick flashes and never solves anything. The possibility of real connection feels almost hidden, as if Flattery herself were afraid of making too much of it.”

–Peter C. Baker on Nicole Flattery’s Nothing Special (The New Yorker)

“Seemingly out of nowhere, precociously aphoristic and coolly unsentimental, the debut novel Ex-Wife appeared in 1929 to much scandalized acclaim; originally published anonymously, it brought a life-altering celebrity to its hitherto unknown author, Ursula Parrott, just thirty years old, who found herself not only controversial and an immediate best seller but, more questionably, something of a spokesperson for the ‘new woman’ of the era—a female counterpart to her almost exact contemporaries Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

In the trajectory of her career as in its vicissitudes, Parrott is more akin to Fitzgerald than to Hemingway, whose expatriate characters and stark themes of war, manly valor, and the ubiquity of death-in-life take him far from the domestic dramas of romantic disillusion, marital strife, and divorce that preoccupied Parrott and Fitzgerald and made them, each for a vertiginous while, rich. Like Fitzgerald but from a woman’s perspective, Parrott examined the fraying social fabric in the aftermath of World War I, the final vestiges of a Victorian era in which the place of a woman was defined almost exclusively in reference to men: fathers, husbands, ex-husbands, lovers …

Ex-Wife is a sharply observed, intimate account of a failed marriage, several failed love affairs, an abortion, numerous alcoholic interludes and one-night stands, and an abrupt, pseudohappy ending when the ex-wife decides, for purely pragmatic reasons, to marry a man she doesn’t love…At its most entertaining Ex-Wife is a Broadway play in novel form, with briskly clever dialogue tending toward the comic-aphoristic, as if Dorothy Parker, Noël Coward, and Oscar Wilde had collaborated to examine the war between the sexes in the post-Victorian era.”

–Joyce Carol Oates on Ursula Parrott’s The Ex-Wife (The New York Review of Books)

“Impeccably literary, emotionally satisfying, yet unexpectedly unsettling … Hadley always delivers fiction that cuts to the quick … It could sound like a slight to be called dependably brilliant, but unquestionably, that’s what she is. She writes with an unrushed assurance and confidence that breeds comfort …

In her short stories, there’s less space to tone and then flex those literary muscles. It is essential to be nimble. While her novels are exquisite, knitted with plot and deep character development as well as a keen sense of space, her short stories lose nothing of that depth in their brevity. Hadley’s stories flicker vividly as powerful vignettes that compress personal histories, offering the reader entry into a brief period of time in which the characters upend perceptions.”

–Lauren LeBlanc on Tessa Hadley’s After the Funeral (The Boston Globe)

“While never as deeply mired in paranoia as the vertiginously indeterminate fictions of Philip K. Dick, this is a world where agency and identity are always in doubt. Do these feelings of love belong to you or have they been planted? Is the terrorist acting of his own volition, or is he a meat-puppet, under the sway of shadowy controllers elsewhere? …

From the rainy neon of Blade Runner to the Vanta-Black corporate Japan of Neuromancer, Anglophone near-future speculation has long had a streak of Orientalism, a fascination (often admiring) with the liquid modernity of East Asian urbanism, and the distinctiveness of the region’s approaches to technology. After the global success of Cixin Liu’s Three Bodies trilogy, American publishers are belatedly bringing Asian science-fiction narratives to an Anglophone readership that has a demonstrable hunger for its culture in various forms. Counterweight is also, in a small way, an expression of soft power, part of a wave of South Korean film, popular music and literature that has in recent years given Seoul an unprecedented global cultural clout …

The novel’s speculations about human agency resonate in the current moment, when American tech C.E.O.s oscillate between issuing sonorous warnings about the existential risks of the A.I. systems they’re developing and breathless hype about brain-computer interfaces.”

–Hari Kunzru on Djuna’s Counterweight (The New York Times Book Review)

“The deeper questions about Williams’s transformation are the stuff of endless debates and dissertations, fuelled by interviews, letters, memoirs, biographies, and Williams’s own writing, including posthumous publications. Most of us don’t mind literary grave robbing, especially when it comes to authors we love, in which case we don’t mind cradle robbing, either: the boyhood diary of F. Scott Fitzgerald, the miniature books of the young Brontë sisters, the childhood newspaper of Virginia Woolf.

In this spirit, New Directions is publishing a volume of the early work of Tennessee Williams, who died forty years ago. Slightly less jejune than the abovementioned efforts, this set of short stories is more like the university-era poetry written by T. S. Eliot in the notebook he titled Inventions of the March Hare, or Vladimir Nabokov’s blank-verse play The Tragedy of Mister Morn, which he wrote as a twentysomething … Like the early sketches of a great portraitist, these stories feature the outlines of the characters—spinsters, sirens, hotheads, and ministers—whom Williams later made famous in plays like The Glass Menagerie, A Streetcar Named Desire, and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.

The promise of juvenilia is that it will reveal how the person became the artist, exposing the sometimes awkward process by which he fashioned himself through apprenticeship and experimentation. The Caterpillar Dogs fulfills that promise, but its real appeal is something else entirely: not a revelation but an affirmation, the chance to be reminded of what we loved about Williams in the first place.

–Casey Cep on Tennessee Williams’ The Caterpillar Dogs: And Other Early Stories (The New Yorker)