Russell Banks on the Time He Fled Bread Loaf with Nelson Algren

Algren Got Fired, Banks Made a Friend

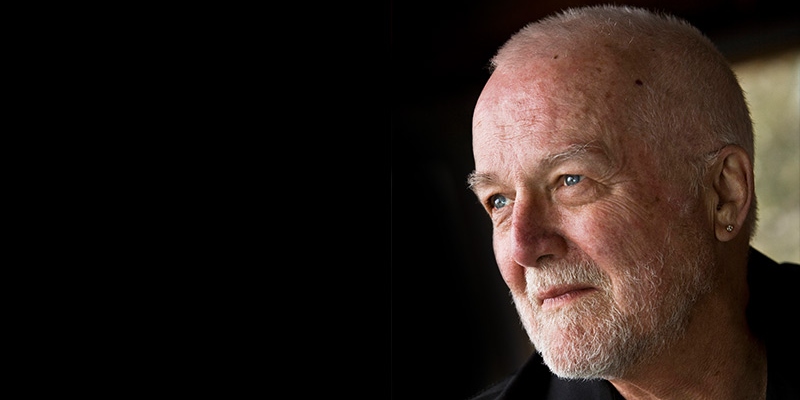

My idea of Russell Banks, who died this past weekend at 82, comes from multiple sources: his dark glimmering novels, like Cloudsplitter; the cinematic adaptations that also demonstrated the generosity of his vision; and the man himself, with whom I never spoke, but who I saw speak, in ways I could never forget, at events with the New York State Writers Institute, in Albany and Saratoga Springs.

I think of him as an upstate New York writer. Say “Russell Banks” to me and through my mind pass images of people in big jackets, of snow, trees, cars not doing well. He wrote about much more than that, but in his work there’s a commitment to people who live on some sort of fringe in a way that’s meaningful far beyond their own remote circumstances—which is how I think of upstate New York people.

When I started making a podcast for the New York State Writers Institute, I found an old exchange between Russell Banks and Don DeLillo about a real-world figure who lived on the margins but also very much at the heart of things: Nelson Algren, a mentor to Banks and DeLillo, and another chronicler of America’s divergent characters. Here’s a transcript, below, from Banks’s reminiscence on his 1960s encounter with Algren. It’s a record of being outside it all and in the thick of things, all at once—an account of literary adventure and misadventure, of grim reality and artistic possibility, of a durable and inspiring literary character that Banks will always represent to me.

–Adam Colman

*

Russell Banks: As a young writer, you have these fantasies about yourself and about literary history, I suppose. I was a plumber at the time, in the early 60s in New Hampshire. I hadn’t been to college or anything. I was writing on my own. And I read an advertisement in the Atlantic Monthly for a Bread Loaf Writers Conference. I hadn’t any idea what a writers conference was. But Nelson Algren was going to be teaching there. Now this is peculiar. I thought he was a Chicago guy, a writer of the streets and the downtrodden and so on, and now he’s going to be up in Vermont—Bread Loaf Writers Conference—teaching.

But nonetheless, I sent a manuscript up, the novel I had written, a terrible novel called The Plumber, as you might expect, in hope that Algren would read it. And he did. I was given a fellowship. I went up there, he did read it—or he skimmed it, is what he said. “I skimmed it, kid.”

He said, “This is a good paragraph here.” And then he’d leaf through about 40 pages, and he’d say, “That’s a good paragraph right there.” And then he’d leaf through another 40 pages: “There’s a good paragraph.” But at the end, what he said was, “You got it, kid. You got the talent, but you only got it here and there and there. And you got to make a whole book that has the same as those paragraphs have.”

I said, “Thank you, Mr. Algren.” And that was really as much as I could hope for. And then he said—and I’ll just finish the story out a little bit, because it gives you a sense of the idea of who he was—he said, “I see you got some wheels.” I had a pickup truck at the time. And he said, “I see you got some wheels. I want to get the hell out of here. This place is driving me nuts. Let’s go down to town, Middlebury, and have some beers.” And so I said, “Sure, Mr. Algren, anything you say.”

He said, “I see you got some wheels. I want to get the hell out of here.”And I drove him into town and we started drinking. And then he got a little tired of that. And he said, “I got a pal up here named Paul Goodman, somewhere in Vermont. Let’s go see Paul Goodman.” And so we drove to see Paul Goodman, and we stayed there for about three or four days and then eventually drifted back to Bread Loaf, which was run then by the poet John Ciardi, who was incredibly pissed off because his teacher had left with one of the students and had disappeared into the wilds of Vermont and then showed up three or four days later.

So he fired Algren, and I was only there because of Algren. He had a plane ticket back to Chicago that was a week later. And so we went back to my apartment. I had a little flat in Concord, New Hampshire. I had time on my hands. And so we sat around and talked, and I had never had talk like this before in my life. I had never met a real writer who had been in the world, who was an adult, whom I admired and whose work I revered. And he told stories and he introduced me to this big world out there, of which he was both a part and not a part.

It was this wonderful mingling of cranky outsider-ness on the one hand, and enthusiastic embeddedness in the literary world that I had never, never met before. It did change me. We became friends. We stayed in touch until he died. But that was the essence of him for me at that time. And his work embodied that. It was both highly literary, deeply cultivated, and yet it was of the streets. It was the kind of writing you could only do if you identified with people who were completely unlike you—which was the case with him.

*

Listen to Russell Banks in on The Writers Institute, from the New York State Writers Institute and Lit Hub.