Rufi Thorpe on the Narrative Role of the Bystander

Writing Ordinary People Who Witness the Extraordinary

I am often characterized as a novelist who writes about friendship, and I am, but the truth is that I don’t set out to write about friendship. I just wind up there because my favorite novels are all versions of what I call The Gospel of Joe Schmo. An ordinary person tells the story of their friend, someone extraordinary, who touched their life and changed them forever. Sometimes the extraordinary person is too good for this world, as with Jesus Christ, or Billy Budd, or Owen Meany, sometimes he is insane, like Captain Ahab, but most often he is both: a Jay Gatsby, or a Sophie who has made a choice. It is, of course, the ones who are both that interest me the most. The Human Stain, My Brilliant Friend, the Sherlock Holmes stories, Heart of Darkness, My Antonia, Breakfast at Tiffany’s are all told in first person from the point of view of an almost peripheral character. Even Wuthering Heights is actually told by Nelly, whose mother was a servant in the house.

As a child, wandering through the paperbacks that littered our house, I was always fascinated by stories of those who had been maimed or disfigured by the truth. Characters who had flown too close to the sun, or who had learned something unutterable. Such stories, I learned, could not be told by the person who had burned their hands by touching truth itself. At first, I thought it was because the truths they learned were incommunicable, and the closest we could get was to watch the truth happen to them in slow motion. And then I thought it was because such fantastical stories wouldn’t be believed unless they were told by someone from regular life who swore up and down that they were true.

But now I think we need Joe Schmo because the Extraordinary One, christ or no, is not inherently likeable. If Joe Schmo didn’t show us how to love them, didn’t hold the camera steady on the few places safe to look, we might just turn away.

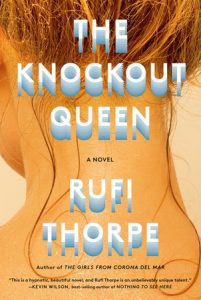

It has always been the recounting of these larger than life figures that fascinate me: in my first novel, The Girls from Corona del Mar, the story is told by Mia about her childhood friend Lorrie Ann whose life has taken on tragic dimensions that verge on the mythical. In my most recent book, The Knockout Queen, the story is told by Michael, a straight A student who works at Rite Aid after school and finds men online to have sex with in cars, about his next door neighbor, Bunny Lampert. A literally larger than life character, by the end of high school Bunny is six foot three and two hundred pounds with the abs of a ninja turtle and the face of a boy angel. The things she does and the price she has to pay both alter the course of Michael’s life, and though their friendship has long lapses, Bunny is the tragic, beautiful thing that Michael can’t stop seeing, even with his eyes closed. The book is, in this sense, a gospel.

*

Robert Penn Warren, All the Kings Men

(Mariner Books)

One of the first novels I fell in love with in this category was All the Kings Men, which, despite its fame, I find other writers my age have not often read it. I was about fifteen when I read it, and God knows why I decided to, but I remember reading it on an airplane and suddenly having the vertiginous sense that I was going to fall—that Robert Penn Warren was going to pull on every slat of reality until the whole thing collapsed. It is a weirdly sensual novel, an alive and idiosyncratic and problematic novel, about the rise and fall of a politician named Willie Stark, loosely based on Southern politician Huey Long, (and eerily reminiscent of Donald Trump.) It is a rapturously bleak book essentially concerned with documenting the break down of moral order, those things which, like Humpty Dumpty, once broken can never be put back together again.

After reading All the Kings Men, it wasn’t that I thought Robert Penn Warren was right, or wise, or that anything I had read was true exactly. In fact I felt a reflexive resistance to the almost unremitting lyrical rhetoric of the novel, a sucking undertow I felt a need to dig my toes into the sand against. But I did feel as if I had met someone I had known in my dreams—the sense of Penn Warren’s consciousness on every page was huge and monstrous, and I knew that no matter what I did, I would never exactly escape that book.

Banana Yoshimoto, Goodbye Tsugumi

(Grove Press)

Goodbye, Tsugumi by Banana Yoshimoto, by contrast, was a peaceful, almost weightless haunting. The short novel is narrated by Maria about her cousin Tsugumi, a chronically ill girl who she describes this way: “She was malicious, she was rude, she had a foul mouth, she was selfish, she was horribly spoiled, and to top it all off she was brilliantly sneaky. The obnoxious smirk that always appeared on her face after she’d said the one thing that everyone present definitely didn’t want to hear–and said it at the most exquisitely wrong time, using the most unmistakably clear language and speaking in the ugliest, most disagreeable tone–made her seem exactly like the devil.”

I mean—I think that passage is on the first or second page, how could anyone fail to read on? Tsugumi is transcendently bad, luminously wicked, and by the end I loved her painfully.

Junot Diaz, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

(Riverhead Books)

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, perhaps my favorite of Junot Diaz’s books, seems as though it is in a wonderfully jazzy third person, but is revealed to be narrated by Oscar’s college roommate, Yunior, as the book goes on. A sweet, fat, love lorn science fiction nerd, Oscar Wao often pains and frustrates Yunior, who has drunk deeply of the machismo kool-aid. Why can’t Oscar be some other way? Yunior wants to know.

“—Nothing else has any efficacy, I might as well be myself

—But your yourself sucks!

—It is, lamentably, all I have.”

Oscar falls hopelessly in love with a prostitute named Ybon in the Dominican Republic, and even after being beaten nearly to death by her boyfriend’s crew, can’t stay away. In the end, Yunior can’t save Oscar, though Oscar manages to save him.

Taffy Brodesser-Akner, Fleishman Is In Trouble

(Random House)

Of all the books on this list, Fleishman Is In Trouble might be the one that conforms least to the pattern, even though it is technically a perfect match: narrated by a peripheral character about a man, the narrator’s friend, Toby Fleishman, who is, if not larger than life in a messianic sense (though he is martyred and he would be the first to tell you!), then at least larger than life in a Babbit kind of way, just the sort of ordinary man a certain kind of American novel is supposed to be about. Toby, who has tried in every way to be a good husband, who is empathetic and kind, who does more than his share of the cooking and cleaning and childcare, is newly divorced and pretty excited about it, when his ex-wife disappears sticking him with the kids. I do not want to ruin it, so I can’t say much else, but I will say this: the roles and rules of narrator and subject here are more complicated than they seem.

Joseph Kertes, The Afterlife of Stars

(Little, Brown and Company)

There is a whole subgenre of Gospel of Joe Schmo that might be called the Gospel of Little Joe, wherein the peripheral character is a child narrating adult events beyond their comprehension, who, precisely because of their lack of fluency in the adult world, are able to see and report the situation more poignantly. Shane and To Kill a Mockingbird are both great examples.

But one of my favorite recent novels to use this narrative position is The Afterlife of Stars by Joseph Kertes, which is narrated by 9-year-old Robert as his family flees the 1956 Russian occupation of Budapest. Robert, who asks sincerely if instead of leaving they could maybe just get the Russian’s to like them, Robert who sneaks chocolates from the bowl on the dining table as Russian soldiers toss their apartment, Robert who muses about a favorite clawfoot table he likes to hide under: “When I was much younger, I thought that this unlucky lion had grown a tabletop instead of a head, but when my brother taught me the facts of life, I realized that a lion and a table had lain down together to make this child.”

In Robert’s case, the larger than life figure is mostly his older brother Atilla, a troublemaking, wildly curious and brave boy, although the stage and the stakes of the novel are quite a bit bigger than these two brothers. Almost every time Atilla speaks he says something wondrous and strange, things that I think about on a daily basis even though I read the book years ago. At the start of the book, Atilla complains to his little brother that semen is such a bland color, giving no hint how important and vital it is. “‘Give it something more, ‘ I would have said to the Lord. ‘Color isn’t everything. Give the little sperms horns, or feathers.’”

The Afterlife of Stars is the funniest tragic novel I know, and if you only read one book on this list, please God let it be this one. (The author, Joseph Kertes, has a new book out called Last Impressions which is also excellent.)

__________________________________

The Knockout Queen by Rufi Thorpe is available now via Knopf.

Rufi Thorpe

Rufi Thorpe is the author of The Knockout Queen, a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner award; Dear Fang, with Love; and The Girls from Corona del Mar, which was long-listed for the International Dylan Thomas Prize and the Flaherty-Dunnan First Novel Prize. A native of California, she currently lives in Los Angeles with her husband and two sons.