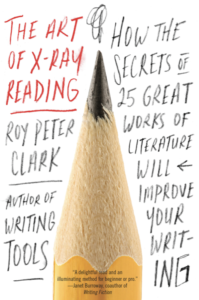

The following is excerpted from Roy Peter Clark’s The Art of X-Ray Reading: How the Secrets of 25 Great Works of Literature Will Improve Your Writing and first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

*

It was author David Finkel who taught me to “report cinematically.” This was key, he argued, to writing a story that feels like a movie, using the variety of camera angles available to the cinematographer, from wide establishing shots to extreme close-ups. Creating such a story, writing coach Donald Murray advised, requires the author to “alter the distance between the writer and the subject matter.” Out in the field, this means standing on a hilltop to observe and describe the battlefield below, then getting close enough to read the tattoo on the back of a soldier’s hand. These days, such images can be captured in still shots and videos via the cell phone. For the dutiful writer, a notebook is the best kind of camera.

Where did the creators of cinema learn to write cinematically? There were precedents in the history of the visual arts, from cave paintings to tapestries to landscape paintings to portraits to photographs. Some of these showed scenes from a distance, others from close up. But where did those visual artists learn the master tricks of distance, perspective, and point of view?

I am about to make the case that it was the oral poet, then the writer of texts, who invented and perfected forms of visual composition. Homer surely had his moments. He could render an establishing crowd shot:

And soon the assembly ground and seats were filled

with curious men, a throng who peered and saw

the master mind of war, Laertes’ son.

And he could do the close-up, as when, upon his return home after a 20-year absence, Odysseus is revealed to his old nurse by a scar from a wound inflicted long ago by “a wild boar’s flashing tusk.” The moment is vivid and appealing to the senses:

This was the scar the old nurse recognized;

she traced it under her spread hands, then let go,

and into the basin fell the lower leg

making the bronze clang, sloshing the water out.

Sometimes a visual image is projected directly from narrator to audience, but at a more sophisticated level, it can come through the eyes of a character or characters. One name for this effect is “point of view.” Suddenly we are seeing what a character sees and feels—the scar of the returning hero through the eyes and under the hands of his aged nurse.

One of the most interesting and chilling examples of pre-cinematic visual writing comes from the Roman poet Virgil, author of the epic Aeneid. In a 2006 translation by Robert Fagles, the poet describes a powerful storm at sea brought on by the goddess Juno against warriors trying to escape the aftermath of the Trojan War:

Flinging cries

as a screaming gust of the Northwind pounds against his sail,

raising waves sky-high. The oars shatter, prow twists round,

taking the breakers broadside on and over Aeneas’ decks

a mountain of water towers, massive, steep.

Some men hang on billowing crests, some as the sea

gapes, glimpse through the waves the bottom waiting,

a surge aswirl with sand.

Let’s understand what we are seeing here. Through the narrator’s description we see wind pounding on the sail, with waves rising above the height of the ship, then crashing down upon it, shattering the oars and twisting the ship around. The waves ascend to the height of a mountain, with some men swept overboard, clinging to the crests, and staring down. Into what? Into the sandy bottom of the sea. The place that awaits them: their sandy, watery grave. Two millennia before anyone dreamed of an aerial shot or the special effects used in the movies Titanic or The Perfect Storm, there was old Virgil creating—in language—the vertiginous seascape of the drowning sailors.

The cinematic idea of seeing things from a distance and then zooming in continues to be a favorite move of creative filmmakers. Famously, Alfred Hitchcock showed us how this could be done in a single continuous shot. In the 1946 movie Notorious, starring Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman, the leading lady is seen at a festive party in a huge mansion from the vantage point of someone at the very top of a tall spiral staircase. Bergman’s character seems relaxed and social. Chatting with her is Claude Rains, a former Nazi operative, greeting guests, until the camera pans through the air, getting closer and closer, until it moves to the left of her figure and down to her left hand, which is curled shut. Then she opens it slightly, and the tightest close-up reveals for a second that she is holding a key. The whole scene takes about 40 seconds.

While I’ve described these movements—from close-up to distance—as cinematic or literary, what makes them most powerful is that they are human. It is the way we see. As I sit at my computer, I see letters track across my screen as my hands move about the keyboard. I look up and to the right and see on the wall a political campaign poster from the 1930s featuring my grandfather Peter Marino. I look down at my left hand and see a tiny scar in the shape of a star sustained 30 years ago in a softball game. Now I look up and see a blast of light and blue sky through the skylight above my desk. A crisscross of oak beams supports the structure. My eyes return to the computer screen. Keyboard, poster, scar, skylight, keyboard.

Why turn your notebook into a camera? When it comes to the marriage of craft and purpose, novelist Joseph Conrad said it best: “My task.. . is, by the power of the written word to make you hear, to make you feel—it is, before all, to make you see. That—and no more, and it is everything. If I succeed, you shall find there according to your deserts: encouragement, consolation, fear, charm—all you demand—and, perhaps, also that glimpse of truth for which you have forgotten to ask.” Make me see.

*

Read more on cinematic writing:

Sarah Kozloff on what we mean when we use the word “cinematic.”

Calvin Kasulke on what actors can show writers about dialogue.

Jen Silverman on starting to write for television.

David Lowery on interpreting Sir Gawain and the Green Knight on film.

*

Books with a Rich Cinematic Quality

RECOMMENDED BY ROY PETER CLARK

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

John Hersey, Hiroshima

Laura Hillenbrand, Seabiscuit

__________________________________

From The Art of X-Ray Reading: How the Secrets of 25 Great Works of Literature Will Improve Your Writing by Roy Peter Clark, published by Little, Brown Spark.

Roy Peter Clark

Roy Peter Clark is the author of books on reading, writing, language, and journalism. His most popular is Writing Tools: 55 Essential Strategies for Every Writer. His most recent is Murder Your Darlings, a writing book about writing books. Since 1977 he has taught writing at the Poynter Institute in St. Petersburg, Florida, to students of all ages.