Romance In the White House: What George Washington Wrote To His Wife

Dorothy Hoobler and Thomas Hoobler on Presidential Love Letters Throughout the Centuries

When a man writes a letter to a woman he is in love with, he generally has one purpose: to persuade her to love him. There are many ways to do this. Some are clever; some are not. Perhaps the clumsiest in this section is in Ulysses S. Grant’s letter to Julia Dent. He drew twenty-one long dashes on the paper and wrote, “Read these blank lines just as I intend them, and they will express more than words.”

Well, of course Julia wanted words more than dashes, but she had to specifically ask him to express his affections—and, eventually, she received them. You’ll find those in this section, too.

At the other extreme might be John Tyler, who expressed himself in language as flowery as any Southern gentleman of the 1810s would: “From the first moment of my acquaintance with you, I felt the influence of genuine affection; but now, when I reflect upon the sacrifice which you make to virtue and to feeling, by conferring your hand upon me, who have nothing to boast of but an honest and upright soul, and a heart of purest love, I feel gratitude superadded to affection by you.”

It worked for Tyler. In fact, it worked twice, because after his first wife passed away, he wooed and won another. His second wife, Julia Gardiner, was thirty years younger than Tyler, and in time they had seven children. Closer to our own time is the courtship of Claudia Alta “Lady Bird” Taylor by Lyndon B. Johnson. As a congressman later, Johnson was known for winning votes through sheer persistence—what some called “twisting arms.”

That was the way he won Lady Bird, too. He met her in Texas in September 1934, and after he returned to Washington, DC, wrote her every day with sentiments like this: “Again I repeat—I love you—only you—Want to always love—only you…” He demanded that she write him just as often. After more than two months of this, she agreed to marry him, and they wed in November 1934. They remained together for the rest of his life.

In the end, maybe the best approach is for the lover to convince his beloved that the one thing above all others that he’d rather do is write to her; as John Adams expressed it to Abigail Smith: “Now Letter-Writing is, to me, the most agreeable Amusement, and Writing to you, the most entertaining and Agreeable of all Letter-Writing.”

In the end, maybe the best approach is for the lover to convince his beloved that the one thing above all others that he’d rather do is write to her.

Reading the letters is entertaining, too, as we hope you’ll discover.

*

George Washington to Martha Dandridge Custis Washington

At the end of her life, Martha Washington tried to burn all the letters she had ever received from her husband. Fortunately for us, she missed a few. Scholars disagree on which of the remaining ones are genuine. Only two are generally accepted as coming from Washington’s hand.

Neither was written during their courtship, but George’s feelings toward Martha are evident from the letter below. We do know that their courtship began in the spring of 1758 when Colonel and Mrs. Richard Chamberlayne invited their neighbor, Martha Custis, to pay a visit to their plantation on the Pamunkey River in Virginia. While she was there, Chamberlayne was out for a stroll when he encountered his friend George Washington and invited him to stay for dinner.

Chamberlayne may not have known it, but he was playing Cupid. Martha’s husband, Daniel Parke Custis, had died the year before, leaving his widow a fortune and a grand home named, coincidentally, the White House. Martha was only twenty-six and beautiful. She also had two children and was doubtless looking for someone to be a father to them.

Washington tried to beg off from the invitation. He was the commander of the Virginia militia and was headed for Williamsburg, the colony’s capital, to meet with the governor. However, after Chamberlayne pointed out the desirability of his houseguest, Washington accepted the invitation.

Although called the “Father of the Country,” George Washington had no known biological children. The two young children in this picture are Martha’s grandchildren. The boy was named after George Washington.

Although called the “Father of the Country,” George Washington had no known biological children. The two young children in this picture are Martha’s grandchildren. The boy was named after George Washington.

The dinner was a success, and Washington stayed the night. He finally did leave to keep his appointment with the governor, but it wasn’t long before he called on Martha again. They were married on January 6, 1759, at Martha’s home.

Neither could have guessed that more than sixteen years later, Washington would be chosen to lead the colonies in rebellion against Britain. He was the logical man for the job, because no one else had as much military experience as he did. But it carried obvious personal risks. He would assume command immediately and did not even have the time to return to Virginia to say goodbye to his wife. He wrote the following note without knowing when, or if, he would meet her again.

Phila. June 23d 1775.

My dearest,

As I am within a few Minutes of leaving this City, I could not think of departing from it without dropping you a line; especially as I do not know whether it may be in my power to write again until I get to the Camp at Boston—I go fully trusting in that Providence, which has been more bountiful to me than I deserve, & in full confidence of a happy meeting with you sometime in the Fall—I have not time to add more, as I am surrounded with company to take Leave of me—I retain an unalterable affection for you, which neither time or distance can change, my best love to Jack & Nelly [her children] & regard for the rest of the Family concludes me with the utmost truth & sincerity.

Yr entire,

Go: Washington

Actually, Martha was able to visit him, and the troops he commanded, each winter for the next eight years when the fighting halted. The soldiers were impressed by Martha’s visits, for she knitted socks and other things for them and offered encouragement. The Marquis de Lafayette, the French nobleman who had joined Washington’s army, recalled that she “loved her husband madly.”

__________________________________

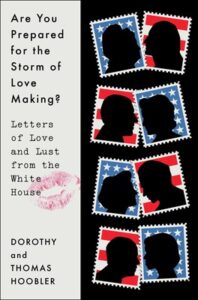

From Are You Prepared for the Storm of Love Making?: Letters of Love and Lust from the White House by Dorothy Hoobler and Thomas Hoobler. Copyright © 2024. Available from Simon & Schuster.

Dorothy Hoobler and Thomas Hoobler

Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler have written many award-winning books for adults and young adults. Their young adult mystery set in medieval Japan won an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Their ten-book series on American ethnic groups, published by Oxford University Press, received many favorable reviews from such publications as The New York Times and the Miami Herald. The Hooblers’ other books for adults include The Monsters, which tells the story of Mary Shelley and the four people who helped inspire her classic novel Frankenstein; and The Crimes of Paris, a collection of famous French crimes that was excerpted in Vanity Fair. Dorothy has a master’s degree in American history from New York University and Tom received his master’s in education from Xavier University.