Robin Sloan on Creating an Expansive and Immersive Sci-Fi Universe

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of "Moonbound"

After a decade working in jobs focused on the future of media at Poynter Institute, Current TV, and Twitter, Robin Sloan has maintained a steady stream of creative projects, many internet related—zines, a newsletter every 29 ½ days, characters for video games (Neo Cab). He’s written a prequel for Penumbra (November 2022), set in San Francisco 1969.

In summer 2020, during the height of COVID, he published Annabel Scheme and the Adventure of the New Golden Gate, a detective story set in a city built on a filled-in San Francisco Bay. It has passages like this: “The burrito cannons blared at noon, and into the sky above the city a fusillade of foil tubes went sailing: carnitas, carne asada, veggie supreme… until their napkin-parachutes deployed.” These burritos were guided by miniscule GPS chips so customers could catch lunch. The novella was published as a daily serial in the San Jose Mercury News and East Bay Times, and through crowd sourcing converted into a web edition, plus that edition’s code is on GitHub, as part of his goal of providing “a lean, fast-loading web e-book template with a kind of definitive sturdiness.”

I asked Sloan to explain the underpinnings for this creative output.

“I’ll confess to a deep curiosity, almost a compulsion, about form,” was his answer. “That goes beyond the ‘mere’ organization of a piece of text, into its overall presentation, the design and engineering of the analog or digital ‘wrapper’ around it. Even the economic terms of its creation. I’m just in love with all of it—the melancholy of old forms fading, the excitement of new forms emerging. All of it!

“I’ll add that, although I produce plenty of work on paper, the digital has a special place in my heart, probably because I grew up alongside it—I’m part of the Oregon Trail micro-generation—and because I find programming totally compelling, in part for its literary qualities. There’s a lot for writers to appreciate here.”

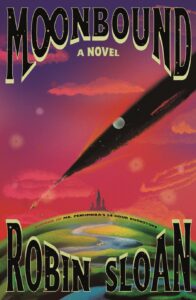

Our conversation about his epic and immersive new novel, Moonbound, took place in the same state (California), via email.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How have the pandemic and recent cultural turmoil affected your life, your work, and the launch of Moonbound?

I wanted a diarist and an encyclopedia; I wanted a camera perched on my protagonist’s shoulder and a satellite view from space.

Robin Sloan: Back in early 2020, I was working on a direct sequel to Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore. It was an interesting project, but/and, my thoughts at that time often started like this: After I finish this one…

Well, the pandemic produced, among many other things, the pointed observation: If you want to do it, better do it now. So I skipped ahead to what I actually wanted to write—the project that loomed “after I finish this”—and that was Moonbound.

JC: After two works of literary fiction—Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore and Sourdough, you’re now full-on diving into the sci-fi fantasy universe with Moonbound. What inspired you?

RS: I think the inspiration was there all along, starting with Penumbra, in which the plot is animated, in part, by a classic series of fantasy novels. Both of my works of notionally literary fiction are tilted strongly toward the fantastic and the science-fictional…so with Moonbound I’ve just approached the material head-on, rather than sidling up alongside it.

I suppose you could say it’s less a matter of new inspiration and more of maturation—and skill!

JC: Sean McDonald has been your editor for all three novels. How much is his sensibility connected to your work? The ways in which he frames and allows experimentation.

RS: I mean, Sean is, for me, absolutely foundational. He was a reader of my feral internet work, long before I ever contemplated writing a novel; he sent me the very first advance copy of a book I ever received—my ticket to the secret society! So, after I completed the first draft of Penumbra, there was no doubt that I’d send it straight to Sean. He and the whole team at FSG made it not only a book but a publication—a distinction I can’t always explain, but can always detect. A production. An event!

I’ve always sensed a “wholeness” and connectivity among Sean’s authors at MCD that I don’t think exists among many other imprints, here and now in the 21st century. In that way, it’s not only his work on my books that’s been formative, but his projects with other people, too. I see Sean pulling off these incredible publishing backflips with writers like Jeff VanderMeer, Nicola Griffith, John Darnielle, Sloane Crosley, and more, and I always think…I want to do that, too!

JC: Your prologue to Moonbound gives us a quick overview of the history of the Anth (“what humans called their civilization at its apex”), and explains how they engineered “a secret passage through time and space” to send seven “scintillating emissaries” they called dragons for a new kind of voyage in 2279. Returning after a year and a day, they decreed “a new law: caution, and darkness, and brutal quiet.” The Anth fought back, and were wiped out. Did this prologue come first ? How did you develop this back story?

RS: The whole thing emerged from the seed of an idea, a sentence fragment really, about “the worst day in the whole history of Earth”. There is plenty of competition for that distinction—and most of the candidates are from long before humanity’s brief era—so the thought raised interesting questions, like, “What made the worst day so bad? What came before it? What came after?”

Moonbound proceeded in both directions: backward toward the Anth, forward into the story.

(Just so I don’t leave people hanging—and this isn’t really a spoiler, because it’s waiting on the second page of the book—the worst-day-making distinction turns out to be this: “a planet that should have been a bright beacon in the cosmos became a fearsome blot.”)

JC: Your narrator for Moonbound is unusual, to say the least. This “chronicler and counselor” combines the intimacy of first person, the suspenseful option of limited third person, and the scope of an omniscient third person. How did you come up with this point of view—who even speaks directly to the reader, offering dates for the present of the novel, September 28, 13777, for instance.

RS: I’m glad to hear all of that came through!

I’ve always been most comfortable writing in first person. I’m also a great appreciator of its particular powers: the way a first-person narrator’s evaluation can marble with their observations. The way a first-person narrator can “subvocalize,” blurring the distinction between what’s thought and what’s said.

At the same time, writing in first person, you lose a lot—not least, the panorama of omniscience. That’s true even in the more “literary” mode of free indirect style, which gets you a bit more flexibility, but still chokes on truly comprehensive statements; still abjures the infodump. (I recall something Kim Stanley Robinson said during a bookstore event, regarding this technique, unapologetic: “DUMP UNTIL YOU DIE!”)

I wanted a diarist and an encyclopedia; I wanted a camera perched on my protagonist’s shoulder and a satellite view from space. Moonbound’s narrator is my attempt to have it all!

JC: Why set Moonbound thirteen hundred years into the future?

RS: Most of the “why”s of my books are connected somehow to my own reading, and this one is no exception: I’ve always been thrilled by far-future science fiction, stuff like the Culture novels of Iain M. Banks or the (hilariously cold and clinical) Last and First Men of Olaf Stapledon. Cixin Liu and Ann Leckie are also great examples. I’m always impressed when a writer pushes out beyond the “readymade” futures, the Blade Runners and Star Treks. These excursions, when they’re successful, add to a shared imaginative stockpile, and I think there’s great value in that, not only literary, but political and moral.

JC: What made you decide to feature twelve-year-old Ariel, who when we first meet him serves as a helper to the hound keeper for ruler, Wizard Malory of the Castle Sauvage? And how did you develop the transfer process, the passage in which Ariel detects the presence of the chronicler (“Who are you?” Ariel whispered…”How can I hear you, inside my mind?”

RS: In a sense, it was a demand of genre! I wanted to write a book that could sit on the shelf alongside The Chronicles of Narnia, The Books of Earthsea, His Dark Materials…so that meant a young protagonist, with lots of room to grow and learn.

However, connected to our discussion of my narrator, earlier, the fusion of Ariel’s youth and openness with my chronicler’s deep context offered some cool opportunities—another case of having it all, or trying.

JC: Another key figure is Alissa Praxa, the girl Ariel finds in a coffin, thus initiating the transfer of the chronicler to Ariel. What is her role, in your scheme?

Problems can be solved. Human history is not—need not be—an endless loop of disappointment.

RS: In this book, I spend a fair amount of time talking about the Anth, the human civilization in Moonbound’s past but our future, and I try to insist throughout—I will insist again here—that the Anth were, or will be, actually fantastic.

That’s all to say, this isn’t another story of human dysfunction: a predictable dystopia. The Anth figured it out: so we can figure it out! Problems can be solved. Human history is not—need not be—an endless loop of disappointment.

Am I wrong? Maybe. Do I insist, even so? I do. The warrior Altissa Praxa is a representative of the Anth, and she, like her civilization, is actually fantastic.

JC: How has the King Arthur legend shaped this story?

RS: Well, I think the notable thing is that it came to me mainly—and certainly most formatively—through retelling and allusion. I’m thinking in particular of T. H. White’s The Once and Future King and Susan Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising. That’s the essence of these stories—and I make this point in Moonbound: that they are constantly being retold, remade, repurposed. Mutated!

I’ll add, however, that this project provided a great reason to dig in and encounter the somewhat more “original” Arthurian mythos. Original-ish. It was terrific to learn that, even in their earliest compiled forms, these were mash-ups, with all the literary seams clearly visible.

JC: How many villains are enough for a novel of this epic proportion?

RS: For my part, I think the ideal number of villains is zero! I’m not sure Moonbound really has a villain. The Wizard Malory is our closest candidate, of course, but there wouldn’t be any story at all—no narrator, no protagonist—without him…so while we can certainly admonish Malory for his selfishness, we might have to thank him, too, for kickstarting the plot.

In all of my writing, I’ve tried to maintain a discipline around “villains”, which is this: They never say anything that I don’t myself believe, to some degree at least. I just don’t think there’s any reason, in a novel of the 21st century, to stuff nonsensical evil into anybody’s mouth. There are enough solid, interesting, conflicting arguments in the world to go around.

JC: What’s your imaginative source for so many magical, empathetic, idiosyncratic animals? Research? Real life? Fantasy worlds you have known?

RS: Yes! Here is where fiction and fact intersect powerfully! The great starting point is of course the glorious stockpile of talking-animal stories, from The Chronicles of Narnia to The Wind in the Willows, from Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH to The Muppets. The vibe is just too delicious to pass up.

At the same time, attending to real biology only makes things more interesting. I’m devoted to the Animal series from Reaktion Books—each one devoted to a single species, covering basic biology, natural history, its role in human culture. They’re totally addictive, and potent fuel for the imagination.

JC: And you make extra virgin olive oil. How do you fit that into your life?

RS: My olive oil company has made my life very seasonal; we spend all of October and November in the olive mill, and much of December packing a flood of holiday orders, so that whole season is “pencils down.”Instead of sitting and writing, I’m up and moving, driving trucks, pushing bins of olives around, operating the mill.

Of course, all of those activities afford some daydreaming time; in that way, the olive harvest provides other creative benefits. A large fraction of the images and ideas in Moonbound began as voice notes captured in spare moments in this busy season.

JC: What are you working on now/next?

RS: Moonbound is (I hope) very satisfying to read on its own, but/and I have imagined it as the first in a series. I’ve started drafting the second book, in which the aperture widens, the world gets bigger—which is natural, of course, because Ariel is growing up. It’s going to be phenomenal—I’m so excited to get these new images and ideas down on the page—so I hope Moonbound finds a readership sufficient to warrant more from this world!

__________________________________

Moonbound by Robin Sloan is available from MCD/FSG, an imprint of Macmillan, Inc.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.