A Woman’s Place is in the Ring: On Gender, Performativity and the Unreal

Rufi Thorpe Considers Wrestling As a Way of Revealing the Inner Self

Being raised by a single mom and my grandmother, I did not grow up watching professional wrestling. We were more of a musical theater and old Shirley Temple films household. But, having married a man with whom I’m raising two wildly physical boys, I suddenly found that WWE was on all the time in our house, and I became transfixed. I think my husband was hoping to get our boys to fall in love with it, so it was a surprise for both of us when I was the one who fell head over heels. After all, what does WWE have to offer a middle-aged woman who doesn’t even really like sports?

I can remember squinting at the TV trying to understand what I was seeing, the over the top drama of it, the costuming and pageantry, why was it so familiar and compelling? Finally I realized: it was drag!

Anyone who has seen a drag show knows that the point of drag is not naturalistic gender impersonation. To draw attention to the drag by performing in a show is to give up the game of passing in the first place. In a similar sense, when people are having a real violent altercation, they seldom dress up in pink spandex and ramble for a few minutes on a microphone first. In both cases, exact verisimilitude is not the point: if WWE were attempting to mimic real violence, it would look like MMA but have rigged outcomes. In much the same way, drag queens like Trixie Mattel are embodying something beyond the feminine–exploring a region of the unreal that can only be called art.

The unreal can have so many flavors and be used to so many ends, but I found the particular flavor of professional wrestling intoxicating.As a fiction writer—someone professionally obsessed with the artificial to the point of spending years of my life building tiny imaginary cities, families, people, each with their own tiny biography, memories and psychological hang ups—I was intrigued. The unreal can have so many flavors and be used to so many ends, but I found the particular flavor of professional wrestling intoxicating. Partly it was the overt silliness of certain of the gimmicks. I adored The New Day with their bright neon colors and hip gyrations and their breakfast cereal “Booty-O’s.” I loved the overtly gothic style of characters like The Undertaker and Paul Bearer, the funeral dirge entry music, the bizarre cremation urn. But most of all, I loved the way it was all mixed together, the silly and the scary, the dark and light, like some kind of insane group project in school where everyone was allowed to pitch in and none of it matched, but all of it was glorious and deeply weird.

Professional wrestling has often been described as soap operas for men, and much of the interest is in following the storylines of the various beefs between wrestlers, but I was fascinated by the doubleness of these plots. There was always a kayfabe or “pretend” storyline, e.g. “Macho Man is mad at Hulk Hogan for being solicitous of his wife and manager Miss Elizabeth,” but then another “real” story under that, e.g., “For real, Macho man is falling apart with jealousy about this angle even though he knows its fake and it is driving a wedge between himself and Hogan who are actually friends IRL.” Every story had a public and private version, and the line between the two often became blurred, with real life giving rise to new angles, and angles giving rise to new real life problems. For a fiction writer, it was pure catnip.

While I fell near instantly for professional wrestling, it took longer to come around on women’s wrestling. Women’s sports stress me out in general because the presumed physical inferiority of women is painful for me. I honestly didn’t find out that women were weaker and slower than men until I was an adult, simply because I didn’t know any men growing up. I didn’t have a father or uncles or brothers. In my household of three women, I was the strongest one and therefore in charge of carrying luggage, assembling furniture, digging holes for trees or fence posts. I have always been strong for a woman and used to delight in beating my friends at arm wrestling.

It was alarming to discover in my teens that even the weakest, nerdiest boy with the noodliest arms could beat me at arm wrestling. When I was in my early 20s I was in an abusive relationship where I learned first hand exactly how little I could physically fight back and how helpless I truly was. And so the constant jokes in the culture about women’s basketball just felt dark to me. It all seemed connected, our presumed physical weakness, our status as second class citizens, our pay disparity, our objectification. We literally weren’t as good as men. Who wanted to watch that?

What I am truly describing here is the way I wound up swallowing some of the cultural groundwater during my own upbringing. I believe that women’s sports will continue to gain in popularity and profitability. I believe that women’s sports are valuable and important. But that doesn’t mean on some level, I’m not heartbroken that we are not men’s physical equals.

Serena Williams, arguably the greatest tennis player of all time, is the first to admit, “If I were to play Andy Murray, I would lose, 6-0, 6-0, in five to six minutes, maybe 10 minutes,” Williams told Letterman. “The men are a lot faster, they serve harder, they hit harder….It’s a completely different game.” That is the reality. And that reality blows. I just—I wish it weren’t so!

Part of the reason I chose to be a writer was because I was reasonably certain that women could be good at it. My feeling of inferiority as a woman shaped every decision I ever made, and it can be difficult to articulate that without seeming like I endorse the position that women are inferior.

So I avoided women’s wrestling for the same reason I avoided most women’s sports: it would force me again to confront this reality. Imagine then, how I felt when I first saw her: Rhea Ripley. The pure, pulsing glory of her. In real life, she is only 5’ 7”, but in the ring she looks 6 feet easy, which she claims is because she “presents herself as tall.” Her height is an illusion, her power is an illusion, of course it is, it always is, but looking at her, I found I could believe in her in a way I couldn’t believe before.

A truth that requires dishonesty, illusion, art, is the most interesting kind.With her black lipstick and her aesthetic of leather and spikes, Rhea Ripley has a clear antecedent in Chyna. Maybe because she was a member of the D-generation X, with their gross air humping and the charming motto “suck it,” I just never loved Chyna, but she was the first female wrestler to be written to beat a male wrestler in a singles match, with victories over Triple H, Kurt Angle, Chris Jericho and Jeff Jarrett. Chyna was only 5’ 10” and 200lbs, and there is no chance she could beat any of those men in a real fight. But the American people believed she could and that was what mattered: that was what gave her power.

There have been many wonderful female wrestlers since Chyna: Ric Flair’s daughter the extraordinary and statuesque Charlotte Flair, Jim “The Anvil” Neidhart’s daughter Natalya (a favorite of mine), goofy yet sinister Bailey, rainbow haired Asuka, fiery and fierce Becky Lynch, and my husband’s one true love, Bianca Belair with her 5 feet of plaited hair. Women in the WWE have gone from bra and panty matches to becoming the heart of the company, and they have done so by coercing the American people into believing in them, loving them, and fearing them.

If you look at pictures of Rhea Ripley before she became Rhea Ripley, she still had an impressive physique, and no doubt she was every bit as powerful as she is now. But she had blond hair that fell past her shoulders, a sport-y gymnast’s look, and a sweet smile. The raw, glimmering power that makes her tagline “Mami’s Always On Top” thrilling instead of comical is coming from the paint, it’s coming from the make-up, from the way she presents herself: it’s coming from her feminine wiles which have been put to new and interesting ends.

In both drag and women’s pro-wrestling, the artificial and performative come together to allow that rare and flickering thing: the expression of one’s true self. A truth that could not be articulated were one confined to reality. And for me, a truth that requires dishonesty, illusion, art, is the most interesting kind. It is one thing to see the fruit on the table and be so moved by its beauty that you need to paint it. That is a good and wonderful impulse, and a lot of my own art making comes from that place: I see people and how they struggle and how they love and how they need, and I am so moved that I feel if I don’t put it into words I will die of it.

But there is another kind of art making impulse: to feel something unnamed, a yearning, an itch, and to find that it can only be satisfied by painting an imaginary fruit that does not exist, a glowing orb of alien fruit that suggests other planets, other worlds. That is the feeling I am always chasing, the ghostly impression the imaginary world has left on the real one.

__________________________________

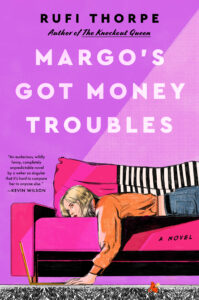

Margo’s Got Money Troubles by Rufi Thorpe is available from William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Featured image: Tabercil, used under CC BY 3.0