Robert Louis Stevenson’s Art of Living (and Dying)

Trenton B. Olsen Explores How the Author Navigated a Lifetime of Chronic Illness

On summer break from his university studies, a young Robert Louis Stevenson worked late into the night. He apprenticed in his family’s lighthouse engineering business but had no interest in the trade. Instead, he had “made his own private determination to be an author” and spent his nights writing a novel that would never see the light of day. Sickly, ambitious, and entirely unknown, he traded sleep for writing. Outside the open window stood the celebrated towers of his family’s achievements that still illuminate Scotland’s rocky coastline.

But looking out into the darkness, he saw only the haunting prospect of his own early death and tried to pen something that would outlive him. Suffering from life-threatening pulmonary illness, Stevenson “toil[ed] to leave a memory behind” him in a monument of words. As the night wore on, moths came thick to the candles and fell dead on his paper until he finally went to bed “raging” that he could die tomorrow with his great work unfinished.

During this time, Stevenson liked to mope around graveyards, where he went, specifically, “to be unhappy.” More fruitfully, he began writing essays. Making a name for himself in nonfiction long before his famous novels, he grappled with “the art of living” and dying on the page. At the point of physical and mental breakdown at 23, he was sent by doctor’s orders to the French Riviera, as recounted in his early essay “Ordered South.” There, he experienced the beautiful setting as if “touch[ing] things with muffled hands, and see[ing] them through a veil.” The young invalid was “not perhaps yet dying but hardly living either.” At his low point, “wean[ed]… from the passion of life,” he waited for death to “come quietly and fitly.”

In a subsequent edition published seven years later, Stevenson added a surprising note to the end of “Ordered South”: “A man who fancies himself dying, will get cold comfort from the very youthful view expressed in this essay,” and reversed its resigned conclusion. Through a maturation process he attributed to experience, interaction, and a great deal of reading, he came to recognize the “self-pity” behind his youthful “haunting of the grave[yard]”: “it [was] himself that he [saw] dead, his virtues forgotten, his the vague epitaph. Pity him but the more for where a man is all pride… and personal aspiration, he goes through fire unshielded.”

*

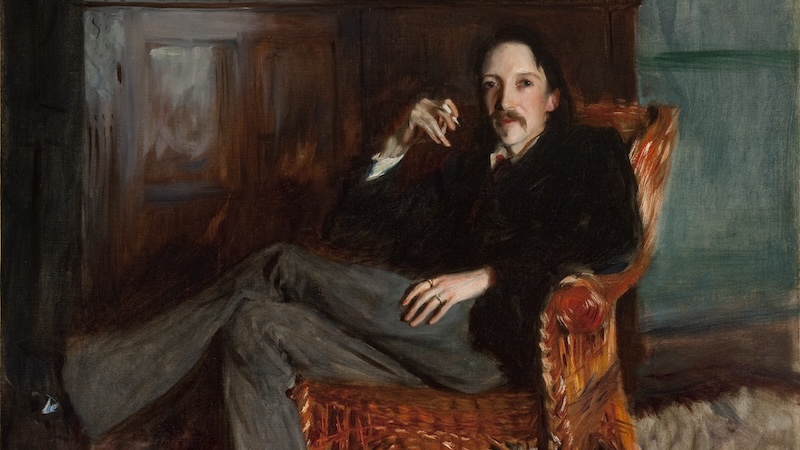

Twenty years later in the fall of 1887, Stevenson arrived in New York a global celebrity. In the previous four years, he had published Treasure Island, Kidnapped, A Child’s Garden of Verses, and, most sensationally, Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, an adaptation of which had just premiered on Broadway. Reporters, publishers, and fans crowded Stevenson before he could get off the ship. For all his youthful longing for recognition, he found the experience of fame “idiotic to the last degree.”

He had come seeking health rather than publicity. For nearly three years, he’d been too sick to leave his house on the English coast. His doctor told him that he likely wouldn’t survive another winter in the British Isles. He often wrote in bed or, when he was in too much pain to manage a pen, dictated to a scribe. When the bloody cough of his lung hemorrhages kept him from speaking, he composed by signing, letter by letter.

But the sickness that once detached him from life had now made him greedy for experience. Making the most of brief periods of relative health, he accumulated several lifetimes worth of adventures. He canoed through France and Belgium, backpacked across a French mountain range with a very stubborn donkey, got arrested as a suspected German spy, inadvertently started a forest fire in California, tried deep sea diving, and crossed the globe to propose to a married woman, to name only a few.

Ordered north this time, Stevenson traveled with his family to Saranac Lake in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York where American Lung Association founder Dr. Edward Trudeau was researching and treating tuberculosis. Despite persistent illness, Stevenson was far removed from the young invalid who felt he had “outlived his own usefulness.” By this time, he had married and taken on stepchildren, lost his father and grieved friends. “The man who has… [family], friend[s], and honourable work to live for,” Stevenson wrote, “cannot tamely die without… defeat.” Though he would always be susceptible to bouts of depression and despair, he resolved to fight illness in order to “bear and forbear, help and serve, love and let himself be loved for some years longer in this rugged world.”

The sickness that once detached him from life had now made him greedy for experience. Making the most of brief periods of relative health, he accumulated several lifetimes worth of adventures.

He wrote most of the novel The Master of Ballantrae that winter, inspired by the Adirondacks and partially set there, as well as some of his best essays for a lucrative contract with Scriber’s Magazine. He called the mountain village “a first-rate place,” and rightly predicted its harsh alpine winter would be good for him. He fought illness by snowshoeing in the woods and ice skating on a nearby pond. Though he got frostbite on his ears, he felt “stingingly alive.”

But Stevenson’s greatest adventure was still ahead of him. His relative improvement in health and literary earnings enabled an audacious gamble: he planned to set sail on a South Pacific voyage. Health resorts were popular for invalids; year-long tropical sea cruises were not. Stevenson updated his will and made it clear that he was prepared to be buried at sea. In fact, while he hoped to recover, he rather liked the idea of such an end. Planning the voyage, Stevenson wrote to a friend, “If I cannot get my health back (more or less) ’tis madness; but, of course, there is the hope, and I will play big.”

*

Two decades after the author’s death in Samoa, admirers gathered at his Adirondack residence—Saranac Lake’s Baker Cottage—to establish the Stevenson Society of America on October 30th, 1915. Organizers, including Associated Press founder Charles Palmer, talent agency creator William Morris, and Mount Rushmore sculptor Gutzon Borglum, established the Robert Louis Stevenson Memorial Cottage: the world’s first site dedicated to the author.

Stevenson’s stay had put the mountain sanatorium on the map. Tens of thousands followed him there. His embrace of life became a window through which others could do the same in a place that saw more than its share of sickness and death. Tuberculosis patients in Saranac Lake, half of whom died within five years of arrival, read Stevenson’s work, sent home Stevenson postcards, and, if they could, walked to the Stevenson Cottage. One tubercular young man was sent to the Adirondack village with the following prescription: “Keep up your courage. Fresh air—fresh eggs—and read Robert Louis Stevenson.” Many found in Stevenson’s work, particularly his essays, “hope to live and courage to die.” And while we shouldn’t view Stevenson only as a figure of inspiration or reduce sophisticated literary art to self-help, neither should we forget or dismiss this part of his legacy.

Of course, when the Stevenson Cottage Museum opened in 1916, death on a mass scale wasn’t confined to sanatoriums. Some criticized Stevenson’s work in the wake of the Great War. The Times Literary Supplement argued in 1919 that his emphasis on adventure, courage, and optimism was no longer tenable: “Violence is not the fashion. Nor for that matter is optimism.” Stories of “adventure” told by “recruiting sergeants” had “cost too much in shattered limbs.” Such critique was partly a backlash against a sentimental, simplistic portrayal of Stevenson as the cheerful invalid. His friends rejected this caricature, which William Ernest Henley called a “barley-sugar effigy” of the real man. When he was sick, H.J. Moors remembered, Stevenson would “cheerfully damn the whole universe.” The Stevenson whose view of life was somehow debunked by widespread suffering was unrecognizable to those who knew him and his work best.

While we shouldn’t view Stevenson only as a figure of inspiration or reduce sophisticated literary art to self-help, neither should we forget or dismiss this part of his legacy.

While some dismissed Stevenson after WWI, others found his writing uniquely suited to the times. In 1916, the London publisher Chatto & Windus released a popular booklet called Brave Words About Death from the Works of Robert Louis Stevenson. Printed small enough to fit in a WWI soldier’s uniform pocket, the compilation was meant to be read in the trenches so that, to recall Stevenson’s phrase, soldiers wouldn’t “go through fire unshielded.” The great WWI poet Wilfred Owen not only read Stevenson but deliberately visited his Edinburgh haunts and sought out the writer’s old friends while being treated for shell shock. Owen’s dreadful description of a soldier killed by poisonous gas in “Dulce et Decorum Est”—“flound’ring like a man in fire,” “white eyes writhing in his face,” “guttering, choking, drowning”—reveals little tolerance for romanticized violence or facile optimism. After witnessing such horrors firsthand in battle and continually in nightmares, Owen turned to Stevenson. Just a few weeks before his own death and the end of the war, Owen wrote to his mother, “At present I read Stevenson’s Essays, & do not want any books.”

*

From the window above his writing desk in Samoa, Stevenson could see the summit of Mount Vaea: a steep 1,500 foot mountain overlooking the Pacific, running with streams and thickly covered with tropical forest. By this time, he knew he could never go back to Europe. Having lived in Scotland, England, France, Switzerland, California, New York, and Hawaii, the nomadic author had finally settled in one place. Vailima, Samoa would be home for the last four years of his life. Stevenson went swimming and sailing, hiking and horseback riding, feeling better than he had in years. “My case is a sport,” he mused, “I may die tonight or live till sixty.” He’d decided that he would be buried at the top of the adjacent mountain and had his window and desk placed specifically for this view. Every time he sat down to write, Stevenson was quite literally facing his own death. But this was nothing new. As he reflected, “I’ve had to live nearly all my life in expectation of death.”

So we find him at the very end, writing ambitious novels and making big plans, working, playing, helping his loved ones and, yes, even relishing salad, adding oil to the mayonnaise dressing “with a steady hand, drop by drop” in his final moments.

Stevenson died in Samoa on December 3, 1894, at 44 years old. After a lifetime of prolonged battles with illness, he died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage. The details of his last day of life reflect his writing on approaching death. In his essay “Æs Triplex” (an allusion to Horace’s line “triple brass / Armored his heart”), Stevenson asks who would “find heart enough” to begin writing a novel or “embark upon any work more considerable than a halfpenny post card… if he dallied with the consideration of death?” Stevenson began his last day writing the novel Weir of Hermiston, which he believed would be his best. He worked “like a steam engine” all morning: writing, once again, at the precipice of death. Afterward, he paced around the house, talking excitedly about the book and his plans for future chapters.

Let’s remember this image of Stevenson: restless in his final hours, still “in the hot-fit of life… laying out vast projects, and… foundations, flushed with hope,… [his mouth] full of boastful language.” Enacting in life what he’d prescribed in his writing, Stevenson worked on the novel he would never finish:

By all means begin your folio; even if the doctor does not give you a year, even if he hesitates about a month, make one brave push and see what can be accomplished in a week. It is not only in finished undertakings that we ought to honour useful labour. A spirit goes out of the man who means execution, which outlives the most untimely ending. All who have meant good work with their whole hearts, have done good work, although they may die before they have the time to sign it.

After devoting that final morning to his writing, Stevenson spent the rest of the day in pursuit of “the art of living.” After lunch, he rode his horse and went swimming. He gave his step-grandson, Austin Strong, a French lesson. His wife Fanny was depressed with an uncanny sense that something terrible would happen. Wanting to cheer her up, Stevenson played cards with her that afternoon. His description of an earlier illness as a coin toss “for life or death” with Hades haunts this final game of chance: “this is not the first time, nor will it be the last, that I have a friendly game with that gentleman.”

As the sun set, Stevenson helped Fanny prepare dressing for a salad for their evening meal. Even this detail resonates with his writing. He described a South American village at the base of an active volcano where “even cheese and salad, it seems, could hardly be relished.” Yet such a precarious position, he reasons, is the “ordinary state of mankind.” So we find him at the very end, writing ambitious novels and making big plans, working, playing, helping his loved ones and, yes, even relishing salad, adding oil to the mayonnaise dressing “with a steady hand, drop by drop” in his final moments.

Suddenly, Stevenson buckled and slumped to his knees. Putting both hands to his head, he asked Fanny, “Do I look strange?” and collapsed. His family and staff helped him into the great hall. Austin remembered him saying, “All right Fanny, I can walk.” They moved him to his grandfather’s large leather chair, and he lost consciousness. Trying to make the fading writer more comfortable, they brought a bed from the guest room and laid him down “for the last few breaths.” They hesitated before removing his boots, knowing he wanted to die with them on.

For all of Stevenson’s raging against death, ultimately, he could accept it. Once, during an especially bloody coughing fit, the typically unflappable Fanny was panicked and shaking. Unable to speak, Stevenson signed for a pen and paper and wrote, “Don’t be frightened; if this is death, it is an easy one.” Notwithstanding his complicated relationship with religion, he wrote prayers for their customary Samoan household devotionals, praying the night before he died,

Suffer us yet awhile longer;—with our broken purposes of good, with our idle endeavours against evil, suffer us awhile longer to endure, and (if it may be) help us to do better. When the day returns, call us up with morning faces and with morning hearts—eager to labour—eager to be happy, if happiness shall be our portion—and if the day be marked for sorrow, strong to endure it.

His final acceptance of death is etched in stone over 9,000 miles from his birthplace. On his tomb at the top of Mount Vaea, the memento mori always facing him at his writing desk, is his poem and chosen epitaph “Requiem”:

Under the wide and starry sky,

__Dig the grave and let me lie.

Glad did I live and gladly die,

__And I laid me down with a will.

This be the verse you grave for me:

__Here he lies where he longed to be;

Home is the sailor, home from sea,

__And the hunter home from the hill.

__________________________________

* 175 years after Robert Louis Stevenson’s birth, his former home is at risk of ruin. The Robert Louis Stevenson Cottage Museum in Saranac Lake, NY needs extensive repairs, and the all-volunteer museum lacks the necessary funding. Learn about the effort to save the world’s first site and finest collection dedicated to Stevenson here.

Trenton B. Olsen

Trenton B. Olsen, PhD is an associate professor of English at BYU-Idaho, author of Wordsworth and Evolution in Victorian Literature, and editor of The Complete Personal Essays of Robert Louis Stevenson. He currently serves as president of the Stevenson Society of America, which owns and operates the Robert Louis Stevenson Cottage Museum. Learn about the effort to save the world’s first site and finest collection dedicated to Stevenson here.