Robert Gottlieb on a Neglected Russian Classic

Western Readers, if They Know it at All, Think of it As the Novel

About a Man Who Never Gets Out of Bed

One of the advantages of getting old—and, believe it or not, there are others—is that you get to reread (and sometimes re-reread) books that you first knew 60 or more years earlier.

Some writers are always with us—Jane Austen, for instance, for people like me; some books we may go back to every decade or two: War and Peace, Anna Karenina, The Idiot—an admired new translation may spur us on; Middlemarch, Moby-Dick, Proust. But other remarkable works drop out of sight, if not out of mind.

Very recently, after playing with the idea for half a dozen years, I went back to one of the most famous of all Russian novels, Ivan Goncharov’s Oblomov, a book that all too many Western readers, if they know about it at all, think of as the novel about a man who never gets out of bed. They’re right in one sense: It’s the central figure of Ilya Ilyich Oblomov who for more than 150 years has supplied Russia with a word for an apparently fundamental quality of the Russian identity: oblomovshchina. Which is the state of being like Oblomov—a man, a member of the landed gentry, who is so without strength of will or purpose that he simply does nothing.

Though he does get out of bed—sort of. His serf-servant Zakhar, one of the major comic characters of literature, helps him put on his stockings and boots and attends to his basic needs, but he’s as lazy as his master. Yet Zakhar is shrewd in his peasant way, whereas Oblomov is the opposite of shrewd: He’s a sublime innocent, completely without guile and without protection from the predatory people who surround him. He’s far from stupid, he’s educated, his looks are appealing, his estate (which he never visits) provides him with enough to live on, although he’s being robbed blind. He just lacks all energy, and his placid good nature protects him from suspicions, resentments, or ambitions. In other words, he’s a hopeless case—and a beautiful soul.

“One of the advantages of getting old—and, believe it or not, there are others—is that you get to reread (and sometimes re-reread) books that you first knew 60 or more years earlier.”

His great friend Stolz is his exact opposite—dynamic, tireless, indefatigable. (Well, of course: He’s half German.) While Oblomov hardly ever strays from his bed, his sofa, and his dressing gown, Stolz is rushing around the country, around Europe, in a whirlwind of productive activity, every once in a while coming home to St. Petersburg to prod and poke his friend into doing . . . something. Anything. Go to your estate and fix it up; come to Europe with me; get back into society. Oblomov would obey if he only could, but he can’t: Yes, of course you’re right, Stolz—but not now.

And then, through his friend, he encounters a woman who rouses his ardor: the beautiful, intelligent, soulful Olga. Can she really love him back? Can it be true that she will marry him? It is true, and he is incandescent with happiness. Except that he ponders, hesitates, procrastinates, postpones. And Olga is a young woman in love with life, with a passion for seeing, doing, seeking. Before it’s too late she steps back, anguished but clear-minded, and eventually finds in Stolz himself the man she can spend her life with. Though even in her happiness with him she is questioning her purpose, almost abandoning herself to an insidious (Russian?) melancholy, from which he determinedly succeeds in rescuing her.

Whereas the 19th-century European novel is almost dominated by women toying with, or surrendering to, adultery, Olga is a woman toying with despair. What is life about? What is it for? How to live it? She isn’t political—she isn’t going to become a bomb-throwing anarchist. She isn’t driven intellectually or artistically—a George Sand, say. She’s the opposite of socially ambitious. She may be the first woman in fiction to find herself in the grip of what we would call an existential crisis. The second major strand of Oblomov is the desperate, painful evolution she forces herself to experience, in contrast to the hero’s resistance to all evolution—indeed, to all action.

In their marital happiness, Stolz and Olga go about their busy, productive life together, almost forgetting their great friend. Stolz has rescued Oblomov from the predatory crooks who have been robbing him, but years go by with no contact between them—Stolz is so busy, Oblomov is so lazy. But eventually husband and wife go to St. Petersburg to bring Oblomov back into their lives. And find him exactly where they left him, comfortably established in his old apartment, and more or less married to the loving and worshipful landlady whose sexy bare elbows and exquisite cooking provide him with all he wants and needs in life. He has rediscovered the secure and undemanding world of his childhood, in which he takes for granted everything that is unstintingly done for him; he’s re-created the world of oblomovshchina.

“There’s a side of me that could happily never get out of bed, given a stack of books and a good reading lamp: I’m Oblomov.”

At least, though, he’s managed to father a little boy, named for Stolz, whom Stolz carries away to be raised by him and Olga and presumably infused with their own life-force. Yet much as they deplore Oblomov’s failure of vitality and stamina, the Stolzes never cease honoring his “pure, pure heart.” His, says Stolz, “is a transparent, incorruptible soul.” A Russian soul.

I must be Russian. There’s a side of me that could happily never get out of bed, given a stack of books and a good reading lamp: I’m Oblomov. But then there’s the side that can’t bear to be without a job to do, without something to accomplish: I’m Stolz. How did Goncharov, back in 1859, know me so well?

From the start, Oblomov was recognized as a masterpiece. “Goncharov is ten heads above me in talent,” said Chekhov. “I am in rapture over Oblomov and keep rereading it,” said Tolstoy. And Dostoevsky came to rank it with Dead Souls and War and Peace. Who are we to disagree?

__________________________________

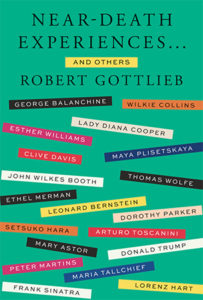

From Near-Death Experiences . . . And Others. Used with permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2018 by Robert Gottlieb.

Robert Gottlieb

Robert Gottlieb has been the editor-in-chief of Simon and Schuster, the head of Alfred A. Knopf, and the editor of The New Yorker. He has contributed frequently to The New York Times Book Review, The New Yorker, and The New York Review of Books, and is the author of Great Expectations: The Sons and Daughters of Charles Dickens, George Balanchine: The Ballet Maker, Sarah: The Life of Sarah Bernhardt, and Avid Reader: A Life. In 2015, he was presented with the Award for Distinguished Service to the Arts by the American Academy of Arts and Letter.