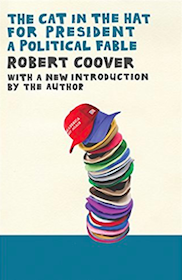

Robert Coover's Long Lost Seussian Satire of American Politics

The Cat in the Hat for President (would be better than what we have now)

The Cat in the Hat for President is a 1968 election-year tale, written in a mouse-infested Mexico City hotel with brass spittoons in the lobby, a temporary hideout from the University of Iowa, where I was then employed. Iowa, like so many universities, was on the boil that spring. The nation still had a citizen army then, and the young were being drafted away to die in a stupid war virtually no one believed in, so there was a desperate urgency about the mounting nationwide resistance, and we found ourselves in the middle of it. Vigilante police teams had been created and thrown into battle, heads had been bloodied, students hospitalized and arrested and charged with conspiracy (some of this can be seen online in my 30-minute documentary, “On a Confrontation in Iowa City”).

We needed a break. My wife Pilar’s Argentinian guitar maestro was in Mexico that spring, so we decided it was time for a few quiet lessons. While she practiced and lessoned, I entertained our three small children. And it was while reading a Dr. Seuss book to them that my eye fell on the little Cat in the Hat symbol on the front cover: “I can read it all by myself.” It looked remarkably like a campaign button, and, by changing one letter, it was one. The Cat’s goofy anarchism resonated, I realized, with that of the current generation of students, all of whom had been brought up on the Ted Geisel (aka Dr. Seuss) stories, and I could count on them going to bat for the Cat who knows where it’s at. Like Mr. Brown, I had my candidate.

I rented the maids’ laundry room on the roof of the hotel and set to work, and by the end of our trip I had a rough draft of the story. As soon as we got back to Iowa City, I gave it a quick slap of the polish rag and sent it off to Hal Scharlatt, my editor at Random House, in the hopes that we could get it out before the election. Random House was also the publisher of the Dr. Seuss books, so maybe Geisel could even provide some illustrations. But the publishers would have none of it. They buried the original typescript in a locked drawer and told my editor to forget it, it didn’t exist. Dr. Seuss was a multimillion dollar business for Random House, and they were taking no chances.

Moreover, Hal was warned that if the story appeared anywhere, I was no longer a Random House author and his own job was in jeopardy. There were no photocopiers in those days. Two typed carbon copies were about max for readability. I had sent the original and one carbon copy to Hal, kept the other one for myself. Hal didn’t hesitate. He slipped his carbon to his friend Ted Solotaroff, editor of the new New American Review, who had already printed one of my stories in his second issue. “The Cat” appeared there that autumn in the fourth issue, just ahead of the elections.

While we were still in Mexico, President Johnson, realizing he’d been duped by a disreputable gang of gloryseeking generals and himself no longer believing in the war for which he’d long served as cheerleader, had announced he would not run for reelection. The well-planned North Vietnamese Tet Offensive had begun and, though stopped at first, would eventually lead to American defeat. In April of that year, Martin Luther King was assassinated, in May Paris was rocked with massive general strikes and the occupation of university and government buildings, and in June presidential candidate Robert Kennedy, brother of the assassinated president, was gunned down. That was the cheerful atmosphere in which the Cat’s campaign was launched.

The Republicans nominated Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew as their candidates, and at the raucous Democratic convention in Chicago, presided over by Mayor Richard Daley, the vice president Hubert Humphrey at his side smiling benignly while outside in the streets Daley’s police were moving violently against the massed protesters, Humphrey was chosen as standard bearer with Ed Muskie as veep. Not long after the story’s publication, Richard Nixon was elected president—easily, until the current one, the worst in American history.

Nixon’s election meant that the war, with sinister Henry Kissinger calling the shots, was only going to worsen on the way to its all too predictable end. Bombs and napalm would soon rain down on Cambodia and Laos as well as North Vietnam. Peaceful protesters in the US were going to get shot. A lot of draftees as well. And, eventually, in spite of all the sacrifices, the Americans would have to flee, their tails between their legs.

The two Cat stories (The Cat in the Hat and The Cat in the Hat Comes Back) provide mock-interpretive background for this story and all the characters are Dr. Seuss characters. The narrator is a cynical party hack named Mr. Brown (you all know Mr. Brown, he’s out of town—though later he came back with Mr. Black), his principal interlocutor and the genius behind the Cat being the monstrous Clark from One Fish Two Fish. The story would appear briefly during the 1980 election campaign as a little book, titled with the original story’s subtitle, A Political Fable. Republican conventioneers would be welcomed at the entrance to their hotel by young women dressed in cat costumes, holding up signs that read “Let’s Make the White House a Cat House.”

–August, 2017

__________________________________

From the introduction The Cat in the Hat for President, by Robert Coover, courtesy OR Books and Foxrocks Books.

Robert Coover

Robert Coover was born in 1932, in Charles City, Iowa. He attended Southern Illinois University, Indiana University, and University of Chicago. His many awards include the William Faulkner Foundation Award for The Origin of the Brunists, REA Award for the Short Story, Lannan Foundation Fellowship, Clifton Fadiman Medal for Pricksongs & Descants, and Independent Press Storyteller of the Year, 2006. His most recent book is The Brunist Day of Wrath. He divides his time between Providence, Rhode Island, and Barcelona.