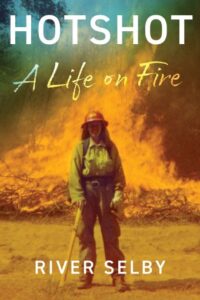

River Selby on Wildland Firefighting, Processing Trauma, and Writing For Your Younger Self

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of “Hotshot”

Early on in River Selby’s riveting memoir, she describes being on her first burn, in Angeles National Forest, the only woman on a crew sent to light a new fire along the road to burn into the main fire, consuming all fuel in its path until both are extinguished. She is adrenalized, knowing that she herself could burn at any moment. “My insides screamed, I kept moving,” she writes. Using a drip torch, she walks slowly, pouring flames into the grass, watching the flames ignited by others in her squad, watching the wind. The work continues for hours, until nightfall.

“This may have been the exact moment I fell in love with being a hotshot,” she writes. “Burning was like entering an alternate dimension….The drip torch became an extension of my arm, fire a liquid expelled from my body. There was no pain. I’d been totally focused, consumed like branches alchemized from solid to smoke. I was cleansed.”

This is the moment when Hotshot grabbed me, embedding me fully in a multilayered universe. It’s rare for a first-time author to manage such a perfect balance of her personal story (fighting fires for a decade, usually as the only female on a crew of the toughest of the firefighting hierarchies, the hotshots); her fraught family drama, the historic missteps in land stewardship that have led to some of this country’s worst fires ever in recent years, and her awareness of the challenges climate changes has brought to the firefighting community today. Hotshot nails it.

Our email conversation spanned the continent, from Tallahassee, where they are completing a Ph.D. program, to Sonoma County, which is riddled with wildfires today, the largest being the Gifford megafire, which has consumed nearly 130,000 acres and is approximately 37 percent contained. (Firefighters battling the Gifford Fire are continuing backfiring operations like the one described in Hotshot in the Garcia Wilderness in an attempt to slow the fire’s spread.) And fire season is just beginning.

*

Jane Ciabattari: In the opening pages of your memoir you write that you began your career as a firefighter in 2000. You were living in Eugene, Oregon, attending community college, and your life “unraveled,” as you put it. Your grandmother died, your grandfather had a fall that led to memory loss. “Bulimia was my primary coping mechanism, along with drinking, drugs, and sex,” you write. A friend recommended signing up to be a wildland firefighter would distract you. Looking back, can you identify what it was that made you say yes to that path? And do you think it was the right decision?

River Selby:Looking back at those months (and years) before I began fighting fire, it’s clear that I had lost my will to live and was looking for an escape from my life. When Kelly showed me her photo album, her demeanor transformed. I saw how much she’d loved the work and hoped I would, too. It was the right decision– a better decision than I could have imagined at the time. In my first draft of Hotshot I wrote about the winter after my first season, when I was twenty.

My friend Peter died from an overdose and I started regularly using heroin, ketamine (before it was well known), methamphetamines and cocaine on a near daily basis while also working as a stripper. It was very dark for me. Had I not had the opportunity to go back and fight fire again, I’m sure I’d have died. Many friends died in the following year. The job saved my life.

JC: You spent ten years as a firefighter. How were you able to document those years and write about them in such detail? Your “album of fire relics,” including an Incident Action Plan (IAP) from your first job? Journals? Photographs? What else?

RS: I kept newspaper clippings, old t-shirts and hats, IAPs, training documents and seasonal summaries of fire deployments (with the names and locations of fires), well-worn books and all my journals, including the small notebooks I carried in my front pocket on fires. Sometimes my crew-mates would draw or write in my notebooks, too. After selling the book on proposal I visited several of my work locations, including hotshot bases, though I never went on base because I was still processing a lot of trauma. These visits were triggering but necessary, and helped unearth memories, which I documented each night. Several of my former crew-mates were generous with their time, letting me interview them. This was essential, because they remembered things I’d forgotten– for instance, one reminded me of a nickname I’d forgotten. Hearing them recall their experiences and perspectives confirmed my own and bolstered my confidence as a writer.

JC: You include sensual details about the fires you battled, including the visual landscape (in your first fire, the Viveash: “Bare, blackened trees with pointed, spindly limbs and black soil that felt strange underfoot, both spongy and brittle.”), the smell (“sweet and repellent, like a puttering campfire”), the feel (“clouds of dust and ash, coating everything, including my mouth and teeth, in fin grit…”). Are these details from memory? Photographs? Journals?

RS: I’m a visual thinker, and the visual elements were drawn from memory, along with the embodied experiences (like eating dirt and ash, being coated in it, the pain, exhaustion, and adrenaline). Others were lifted from my journals. Fighting wildfires is a sensual job, often overwhelming the senses. Whenever I hear a chainsaw, even fourteen years later, I am drawn back into the experience. The same goes for certain plant smells, the chink of tools on rocks, the smell of woodsmoke. I immersed myself in research, books, articles, and videos about wildfires, but also kept my mind open to recollection. When I encountered these memory triggers in daily life I’d pause, letting my past experiences unfold, recording them in writing or voice notes. For years. This was emotionally challenging, but I think it helped create a vivid experience for the reader.

JC: Hotshot is indeed vivid! One element that is central to your firefighting experience is being one of the few women and sometimes the only woman on a crew. Many times you pause to mention your continual awareness of being the only woman in the picture, whether it’s trying to sleep at night in a circle of men with not privacy, no tents, or find a bathroom, climb a mountain with a load of gear, volunteer for a difficult task so you can prove you are as capable as the rest of your crew, try to find at least some sense of trust if not camaraderie. It sounds so wearing. How were you able to keep going? What would you tell your younger self about that experience today? And what have you discovered in the years since about sexual harassment in wildland firefighting?

RS: As a young person I was acclimated to a high level of discomfort, whether it be physical or psychological. I had been homeless several times and raised in a neglectful, abusive environment, although there were bright spots. One of my coping mechanisms was to put myself in opposition to authority or other’s perceptions or ideas of me, and as the sole woman I knew that some of my co-workers expected or wanted me to fail. My desire to prove them wrong was very strong.

I was also a community college dropout who doubted my intelligence and didn’t see many options for employment beyond blue-collar jobs, nannying, housekeeping, or sex work, with a mother and stepfather who, as far as I could tell, saw me as a failure. These factors, coupled with my internalized misogyny, all played a part in my initial endurance, but I started to see my own strengths, too. I surprised myself. Some of the guys were supportive as they saw me getting stronger, which also helped, because I didn’t want to disappoint them.

These dynamics were all unconscious and invisible to me when I was younger, and the book is an embodiment of what I would want to convey to my past self– that my ideas about myself weren’t necessarily true, rather a cultural and familial training into which I was indoctrinated. That I could quit and be okay. But I’m glad I didn’t quit. Many people, especially those of us raised in impoverished (in the widest sense of the word) environments, spend their twenties banging their heads against a wall. If they’re lucky, they survive and learn from those experiences.

The book is an embodiment of what I would want to convey to my past self–that my ideas about myself weren’t necessarily true, rather a cultural and familial training into which I was indoctrinated.

At the time, I thought my experiences of sexual harassment were individual, but in writing the book I learned that they’re not unique, nor did I experience the worst of what can happen. It’s a culture of dominance and shaming that negatively impacts everyone–not only women. And it hasn’t really changed, from what I’ve heard and seen, nor is it only prevalent in firefighting. Sexual harassment and many other forms of (often violent) discrimination are part of American culture. It’s a history that keeps repeating, and we’ve yet to fully reckon with it.

JC: Most readers are as new to the world of wildland firefighting as you were at the beginning. You explain the hierarchies, procedures, equipment, and details of the system and include a detailed glossary at the end of the book. What was your process for including this information in your narrative?

RS: A lot of this was part of the editorial process. Because I spent so much time in that world I needed reminding when mentioning certain terms, methods, and hierarchies. Question marks and nudges to explain. But I worked hard to make them part of the text, rather than simply containing them in parentheses, so the reader could learn through experience, as I had, rather than simply giving names or explanations out of context. That would have been more difficult if I hadn’t had so many years of experience on the ground, fighting fires. It’s not an outsider’s perspective, and the experience of reading the book is, I hope, one that can help readers understand things from the inside.

JC: You came to firefighting with a history of bulimia. Was that exacerbated by the deprivations of being on a hotshot crew?

RS: Perhaps, partially, though not because of any physical deprivations. The job demands emotional suppression. Some dealt with this through drinking, or rage, or controlling others. My tool was bulimia. I also drank, and as I stayed with the job both worsened, though there were of course other factors at play.

JC: This book is more than a personal story. You also include historic elements to illuminate the ways in which firefighting and land stewardship in the U.S. has changed over the centuries. For instance, you describe the West Coast before the Spanish established their first mission in 1769 and how colonization influenced wildlands and fire behavior after that. And how Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir transformed Yosemite (making it more fire-prone) through fire suppression rules. What sort of research was involved in weaving in these historic back stories ?

RS: I think the majority of this book is composed of research-based writing, and my research was extensive, conducted over the course of half a decade. I’m still researching, especially on the science side. I read around fifty books and countless academic articles. I conducted archival research, delving into settler narratives, Indigenous oral histories (often recounted by whites, which must be noted), and primary sources. I spent some weeks at the Newberry Archives in Chicago, which has an extensive archive devoted to American Indian and Indigenous studies. There, I looked through photos, read letters, and pored over government documentation.

I also conducted interviews with scientists and cultural fire practitioners. Obviously not all of this ends up in the book, but I needed a deep understanding of colonization, fire and fire suppression history (both scientific and historical aspects), cultural conceptions of nature, and various ecologies in order to write from an informed perspective. This was sometimes overwhelming, because I knew I couldn’t contain everything in one book, and needed to balance the various storylines while keeping my narrative voice as consistent as possible. I had to remind myself that no book is definitive. It’s part of a larger conversation, which is why I included a list for further reading.

JC: How would you describe your transformation from firefighter to writer? And your transformation from Ana to River?

RS: This is a whole book in itself, or an essay (or several essays)! It was a process of waking up to myself as a whole person. An individual. My mother’s suicide played a part, because it completely broke me down as a person. I was a ghost. All meaning fell away, revealing chaos. I clung to writing, and it tethered me. To what, I’m not sure, but this is how writing has always functioned in my life. A tether, helping me make meaning of a chaotic world and my place in it. I decided to be a writer, and made a commitment to pursue this life no matter what– even if I worked as a nanny and my work was never published, and although I am lucky enough to have a book published, I don’t take that for granted. Writing to me is not necessarily tied to publication. It’s vital to my survival.

I am River. Like coming into my own as a writer, arriving to River was a long process. I’ve had many names and identities throughout my life and was never attached to my name(s). Sometimes I felt confined by them. Identities also, with time, became too small, and needed shedding. A River is always changing, as am I. For most of my life I was ashamed of my changeability. I wanted to be solid. When I arrived to River, I knew I had found my essence. I am not a gender, nor am I genderless. River is simply who I am, always changing.

JC: What are you working on now/next?

RS: I am exploring my next book, which is also my dissertation. It’s still liquid, unformed, but in process. I do know that it will be quite different from this one, and I’m relishing this phase of curiosity and listening. I am currently at Florida State University in Tallahassee (one more year!) pursuing a PhD in Nonfiction with an emphasis in postcolonial histories, North American colonization, and postmodern literature and culture. I’ll likely move back west when I’m finished. I work with archives a lot, specifically linking narrative threads in archival documents from western expansion/colonialism to the ways in which colonialism and white supremacist ideals are currently perpetuated in our country, as well as ecological transformations. My dissertation is a memoir, but I am also working on a sci-fi novella and continue to work on essays and academic work surrounding American, Indigenous, literary/film, and queer history.

_________________________

River Selby’s Hotshot: A Life on Fire is available now from Atlantic Monthly Press.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.