She’s mortified by her appetizer. On the menu it sounded fanciful. Now it just seems decadent, and decadent is always embarrassing. Like Roman orgies in movies where servants are peeling grapes for the reclining emperor, where the guests are eating off human tables—naked women on all fours.

“I feel a little weird eating, you know—I guess I didn’t think it was going to really be gold. What’s it doing? Being a little metallic glaze on whatever this tiny egg is? Whatever bird it came from. I hope not a parakeet from some Thai forced-hatching factory.” She pokes through the thin skin of gold leaf and they watch the yolk seep up. Neither of them says anything when Cate lifts off the gold film and sets it on the rim of the plate. They sit across from each other at a table much larger than necessary for two people eating dinner. It’s a size more appropriate to spreading out maps, plotting a voyage or a war.

“I know, I know. It does seem like what they were probably eating in the dining room of the Titanic. I didn’t know it would be this fancy, hardly anything is anymore. Except this place, I guess.” Maureen’s sympathy has a hollow ring to it. She actually seems quite comfortable spearing a forkful of foie gras (for Christ’s sake), nestled in a pillow of salted cotton candy. Cate has brought up issues of animal cruelty before, and Maureen always seems sensitive in the moment, deeply nodding her support, saying annoying stuff like, “Poor things, they can’t speak for themselves so we have to help them.” But then she will turn around and tuck into something like this.

Cate scans her from across the table. As a costume designer, Maureen of course costumes herself. Her clothes make tiny statements without calling attention to themselves. Odd collars, the occasional hat. She has an extremely articulated tattoo on one shoulder—a Japanese fan. She wears a lot of pale green, also navy, to set off her hair, which is dark red, Botticelli crinkles, both bunched up and falling down.

Tonight would probably be a good time for Cate to reveal her discomfort about over-the-top restaurants like this one. But she can’t find her way to that conversation. Maureen loves expensive dining, and can afford it. She has spent the past decade dressing actors, for plays, musicals, sometimes operas. Operas, Maureen says, are the costume designer’s diamond mine.

But now she has to get serious instead of just looking serious.

In the end, Maureen might be too different from Cate, but they are only at their beginning, and Cate is not ready to give in to that notion just yet. The thing is, Maureen fits perfectly into the future Cate hopes to have. She’s totally adult. She has investments. There’s a financial advisor in the wings. She is funny and large-hearted, ardent in bed, and beautiful in a recovered way that stirs Cate. As though she has sprung back from something difficult, but is made of denser material because of it. Cate still thinks there’s a chance that with her she might make a respectable partnership. Important in a real-life way, as opposed to the elaborately fantastic scenario she spooled out with Dana, who nonetheless remained firmly attached to her partner. Remains still.

“Sometimes I think you might be too good-looking for me.” Maureen reaches across the table to pluck a hair from the cuff of Cate’s jacket. This is a kind of thing she says. Romantic prompts. What would be a good response to this? Cate, by her own standards, isn’t all that attractive. She’s awkward, gangly with her height, as though she’s still adjusting to it. Maybe she has something small going for her, a serious expression, like that of a reporter in a war zone, or a doctor about to give bad news. A face that is flat planes and abrupt angles. She also got her father’s ice-blue eyes, which adds another element to the chill. She does know this severity holds value in particular situations, incipient romance being one.

But now she has to get serious instead of just looking serious. Living casually in the moment seemed so vibrant, but has left her looking over her shoulder at a pile of used-up hours and days, hearing the scratchy sound of frittering. If Graham hadn’t bought the condo for her, she’d still be living in her rental apartment with 72 coats of paint, cabinet doors that stuck even when they weren’t shut. Silver-painted radiators that lay dormant for hours, then banged to life in a mechanical riot that would blast heat through the place in such an overwhelming way that she could leave the windows wide open for those cool February breezes. She has come to understand that room temperature in the demographic she aspires to is a more personally controlled business.

Maureen inhabits this thermostatted demographic. She owns a co-op on Marine Drive, has an Infiniti that still smells new. She’s on the board of something that puts disadvantaged kids into musicals on nights when the theaters are otherwise dark. She has won three Jeff Awards to Cate’s one—Maureen’s for equity productions, Cate’s for one of the sets she did for Adam Pryor. Like all his work, this was a small play with large ideas.

For a long stretch, her career strategy was simply attaching herself to Adam Pryor. They had interlocking artistic views. The plays he directed got serious attention, which brought her sets the same sort of respect. And then he was walking on Wabash one day a year ago, at three in the afternoon, when an elderly woman mistakenly wearing her reading instead of her distance glasses, jumped the curb and killed him instantly. This was devastating to Cate personally; they had an intricate friendship, a matched sense of what was important, what was ridiculous. More prosaically, in terms of work, she was suddenly unemployed. Doing the sets for a play as dismal as At Ease is the kind of thing she thought she was beyond. And yet here she is.

Maureen is saying,“My sister is coming for a visit. I’d like you to meet her.”

“Sure, great. I always envy people who have sisters. Especially when they’re close.”

At exactly this instant Cate is thinking everyone should really hold on to their secrets.

Maureen hesitates, then says, “Yes. We are close.” She suddenly looks uncomfortable. Probably from the goose liver. She pushes her fingers into her big hair, not in a coy way, more maniacal. Like Mr. Hyde rousing himself from sleep in Dr. Jekyll’s laboratory. “What I’m trying to say is, there was a time when we were even closer.”

“When you were kids.”

“No. After we were both out of school and on our own. For a while then we were, you know, involved.”

“Oh.” Something slippery and cold flushes through Cate, the eel-like sensation that accompanies unwelcome information. As she searches for a response, she focuses on the remains of her egg as it is taken away by a silent waitperson, replaced by a teaspoon’s worth of pale green shavings of something frozen and glistening. The server explains the palate cleanser. Cate can’t listen.

Once the server has walked away, Maureen says, “I just don’t want there to be any secrets between us.” At exactly this instant Cate is thinking everyone should really hold on to their secrets, edit the worst lines from their personal résumés. This piece about Maureen and her sister, for example, would have been an excellent edit. Now, though, the cat’s out of the bag. Now the cat is hopping all over the place, demanding attention.

“How did that happen anyway?” Cate tries for a neutral tone, as though she’s asking about a tour of the French countryside on which Maureen and her sister took the optional side trip to see the cave paintings.

“Oh, she was coming off a divorce and she was needy. And of course, this was California. Also the 90s. You know.”

Clinginess or historical period or seaside locale don’t really seem extenuating enough circumstances.

“Were you in love? Was it that sort of thing?” She doesn’t even know why she’s asking. Would it be better or worse if they were or weren’t?

“It was more a way we had of being together. You’ll see when you meet her, Frances is just an intensely charismatic person.”

Cate looks around, suddenly awkward at having this conversation in a public place, but then she notices the hanging glass panels, some elaborate baffling system. The other customers exist somewhere else on the dining matrix, all of them in parallel, convivial but hushed universes.

“This is kind of—well, you know—unusual.”

“I didn’t mean to shock you. By now I see it as something small and far behind me. A tiny part of someone I was for a little while.”

In some precisely measured time frame, the vessel (something between a bowl and a plate) that held the sorbet or granita or whatever is taken away, replaced by a nubbly deck-of-cards rectangle. Sesame-crusted tofu striped with two sauces, pale pink and yellow. The server extends white-gloved hands toward Cate. The hands, palms up, hold a napkin, which in turn surrounds a heavy silver eating utensil with which Cate is completely unfamiliar. As Cate takes this narrow, flat, shovel-like implement, she sees the waitress look for a couple of nearly invisible but definitely extra clicks of time at Cate’s hand, her left. By now, she has a full repertoire of deft moves to replicate the functionality of a complete hand. But having only the first two fingers and a thumb to work with makes this particular gesture look like the claw in a game machine, picking out a toy. This doesn’t bother her. One thing Cate is not self-conscious about is her hand.

__________________________________

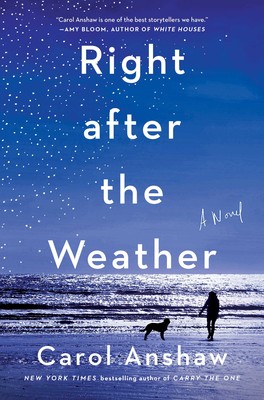

Excerpted from Right After the Weather by Carol Anshaw, published by Atria Books, a division of Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2019 by Carol Anshaw.