Rick Bass on What Hunting Taught Hemingway About Writing

”Death, and learning how to end a story: again, the woods made him into a writer.”

This previously appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Hemingway was a hunter, probably long before he knew he was a writer. Step by step, far from academia, in the cooling shade of the forest, he built and then polished his brain into the generator—creative and destructive—that would power the vessel of his body and his craft. He was always looking for something. This is what hunters do. There is an absence, a need, and they move toward it. Sometimes hugely.

Having never hunted in the manner Hemingway did once he got to Africa, and certainly having not lived in the context of the 1930s, ’40s, ’50s, when all the lead was flying, I yet cannot help but wonder if Hemingway himself did not feel a great ambivalence with regard to Africa’s roving artillery, this caravan of the group hunt, with gun men, trackers, spotters, drivers. Much of True at First Light involves him trying to talk Mary out of her lion-killing lust—even though we know the lion is going to die, else it would not be in his work. That would be a different writer indeed.

There is another aspect in which hunting and fishing (and nature) likely informed the writer. Death, and learning how to end a story: again, the woods made him into a writer. I don’t know what he would have been, without the woods. A boxer. A football coach. A fishing or hunting guide.

Death, and learning closure as a writer: we can see, again and again, how in being so versed in death—drawn toward the thing he feared, and with death the logical terminus of hunting—Hemingway built his brain to serve him as a writer of good endings. Of learning—training, calibrating himself—to be sensitive to and recognize the stillness when a thing is over. This is a more organic and better way of achieving an end—far better than trudging as if on a forced march toward a long-ago predetermined ending. Instead, the recognized or happened-upon ending has more vitality, is more natural, and has greater durability—it permeates one’s body with the five senses. It resonates with the unsuspected, the unknown now known.

Even the craftiest writer who tries to hide a predetermined ending will carry into it some element of trickery, and hence some separation from, some superiority over the reader from whom he or she has been trying to hide it. Often a sophisticated reader will sense this, even without quite knowing what’s up.

When you go hunting, you don’t know quite what you’ll see, and you don’t know when or where you’ll see it. You know only what you want. You walk—quietly, carefully—until you see the quarry. You come quietly into a clearing and there it is. The End, after a lot of hard damn work.

The guns and alcohol are so overwhelmingly present, in True at First Light and elsewhere, as is death, all manners and ways of it, things crashing down around him. Hunting equals death for Hemingway, and closure, finality, control—the closest space and condition he could find to peace, or contentment.

For many of us, nature and even hunting is life and searching, not death and closure, but for Hemingway death was the face of nature—a nature he loved—and in this intimate relationship, Hemingway and nature, as with the relationship between Hemingway and himself, he was on the fence, on a high knife ridge; it could have gone either way. He went into the woods as he went into his prose each day, desperately, fully intent and present, and from the beginning, this shaped the brain he would use later, and through his various batterings and concussions and other debilitations, all his life.

Again, we see it at the very beginning in “Indian Camp”—the bliss and wonder of the artist’s innocence, and the child’s contented innocence, with death nonetheless just beyond. This is an early innocence; the score is still tied essentially zero to zero. It is an innocence that labors like a boatman rowing ever forward.

Even his little writing rules were like a hunter’s: first and foremost, be aware of the wind. Don’t spook one’s quarry. Pay attention to the periphery of things—the calls of birds. (In True at First Light there’s a splendid brief description of Hemingway hearing the alarm call of some small bird and knowing the bird was not scolding at them; that something else, just a little farther on, was on the move.)

His famous blue flame advice about a writer leaving off work each day when you know where you’ll pick up the next: this is the mind of the hunter who, the night before, studies his or her maps intently, dreaming where he or she will set out to the next morning. And, most famously, the iceberg. To a hunter, it is exactly this way, too, if not more so. Everything is unseen, until finally some one small thing becomes visible. The hunter imagines his or her quarry so intensely that it is like a mix between prayer and dream. The hunter inhabits deeply the landscape of the quarry, just as the good writer inhabits deeply the terrain of the story.

______________________________________________

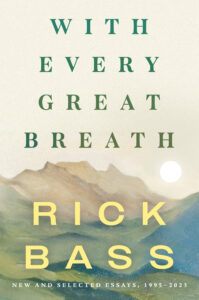

Excerpted from WITH EVERY GREAT BREATH: NEW AND SELECTED ESSAYS. 1995-2023 by Rick Bass. Published with permission of Counterpoint Press. Copyright © 2024 by Rick Bass.

Rick Bass

Rick Bass, the author of 30 books, won the Story Prize for his collection For a Little While and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for his memoir Why I Came West. His most recent book is Fortunate Son: Selected Essays from the Lone Star State. His work, which has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Esquire, and The Paris Review, among many other publications, and has been anthologized numerous times in The Best American Short Stories, has also won multiple O. Henry Awards and Pushcart Prizes, as well as NEA and Guggenheim fellowships. Bass lives in Montana’s Yaak Valley, where he is a founding board member of the Yaak Valley Forest Council.