Richard Avedon, Marilyn Monroe, and Hollywood's Blond Mania

Philip Gefter on the Photographer's Glamorous Cinematic Entrance

In 1954, Marilyn Monroe was already a Hollywood phenomenon. In her earliest cameo in the 1950 film All About Eve, Monroe’s character is briefly introduced to Margo Channing, a grand diva of the stage played by Bette Davis, as Miss Claudia Casswell, a graduate, as her chaperone condescendingly quips, of “the Copacabana School of Dramatic Art.” Miss Casswell is then summarily dismissed, sent off in the direction of a big producer in the other room on whom she is expected to level her feminine wiles.

In a ten-second cut, we watch the bit-part character becoming the outsize star who plays her. Monroe employs an arsenal of subtle optical adjustments, turning on an inner glow and flashing her most mesmerizing smile. Monroe’s technique is on full display here and efficiently recorded in this inadvertent cinematic documentation of her transformation.

Three years later, Monroe’s leading role in the film Gentlemen Prefer Blondes elevated her into a movie star. Her performance as Lorelei Lee is comedic and her rendition of “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” is, for better or worse, the pivotal moment in her career. That same year, a nude calendar picture taken before she became Marilyn Monroe was published as the first Playboy centerfold—providing the kind of “testosterone nip” for the collective male libido that served to catapult her to a level of international fame unequaled at the time.

Avedon with Carmel Snow and Marie-Louise Bousquet, Dior Showroom, ca 1946. Credit: Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos.

Avedon with Carmel Snow and Marie-Louise Bousquet, Dior Showroom, ca 1946. Credit: Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos.

The growing phenomenon of Marilyn Monroe did not escape Richard Avedon’s reading of the cultural moment. In 1954, aware that the wind was blowing in the direction of, well, that platinum “sex goddess” from Hollywood, he took Sunny Harnett to Paris for the collections. Harnett, a slender, nimble model whose blond hair could look strikingly platinum in black and white, was a departure from the dark-haired, toned-down, quietly simmering Dorian Leigh.

After shooting Harnett in Paris for the collections, Dick traveled with her and his entourage of stylists and assistants about two and a half hours to the casino in Le Touquet Plage, on the northern coast of France, near Calais, the gateway for passage to Britain.

Avedon photographed Sunny Harnett at the casino in a variety of evening dresses from the major designers, including Dior, Balenciaga, and Balmain. Yet, in what would become one of his most enduring fashion photographs, he photographed Harnett leaning on the edge of a roulette table in a creamy, sleeveless, figure-hugging Mme Grés gown, which Harper’s Bazaar described as “a long, malleable cling.”

A publicity event was staged only blocks from Richard Avedon’s studio for the movie The Seven Year Itch.

The décolletage cuts at a diagonal across her chest, her breasts swaddled in lustrous fabric, their contours delineated as she leans forward with her weight on her arms. Her gesture, in which the naked shoulder is inched into an almost unnatural forward shrug—so that both shoulders appear to be parallel to the picture surface—accentuates a choreography of bodily curves. The forward shoulder is an Avedon signature with roots in his love of dance. Of course, everything about her gesture, never mind the entire mise-en-scène—the roulette table, the hanging lights, the patrons in black tie in the background—is in service of the dress.

Avedon photographing Veruschka in his studio, 1966. Credit: Burt Glinn/Magnum Photos

Avedon photographing Veruschka in his studio, 1966. Credit: Burt Glinn/Magnum Photos

Sunny Harnett, Le Touquet, August 1954 has the look of a film still in which a simmering Hitchcock blond, say, is waging a sly assessment of the croupier. She is a well-constructed femme fatale aware of her impact and in command of her prey. In all the pictures he made at Le Touquet, Dick would take advantage of Harnett’s sleek and elegant contour with her almost elasticized bodily gestures that derive from the vocabulary of modern dance.

While there is no documentation of the influence of the Monroe effect on Dick, he was acknowledging the “blond” cultural moment by using Sunny Harnett as his model and placing her in a high-toned, sexy setting.

Soon after Dick returned from shooting the collections in Paris, a publicity event was staged only blocks from his studio for the movie The Seven Year Itch. The famous scene in which Marilyn Monroe stands on a subway grate was the brainchild of Sam Shaw, a photographer who made publicity film stills, often shooting on the set during production. On the evening of September 15th, 1954, at Lexington Avenue and Fifty-Second Street, a large crowd of fans and press gathered to glimpse Marilyn Monroe standing on a subway grate in front of the Trans-Lux movie theater as the skirt of her white summer halter dress blew sky-high in the wind of a passing train.

“Oh,” Monroe declared over and over, as they reshot the scene at least 14 times, her hands trying to keep her skirt from flying. “Do you feel the breeze from the subway?” she asked Tom Ewell. “Isn’t it delicious?” Thousands of bystanders cheered as they watched, the noise from the crowd so loud that it rendered the footage unusable. The scene in the film was later reshot on a back lot in Hollywood.

Pictures of Marilyn with her flying skirt were published the next day in the Daily News, as well as in newspapers in London, Paris, Berlin, and Tokyo. The event so infuriated Monroe’s husband, Joe DiMaggio, who was present, that it precipitated the couple’s divorce. For Sam Shaw, though, it was a great publicity coup—the “shot seen round the world.”

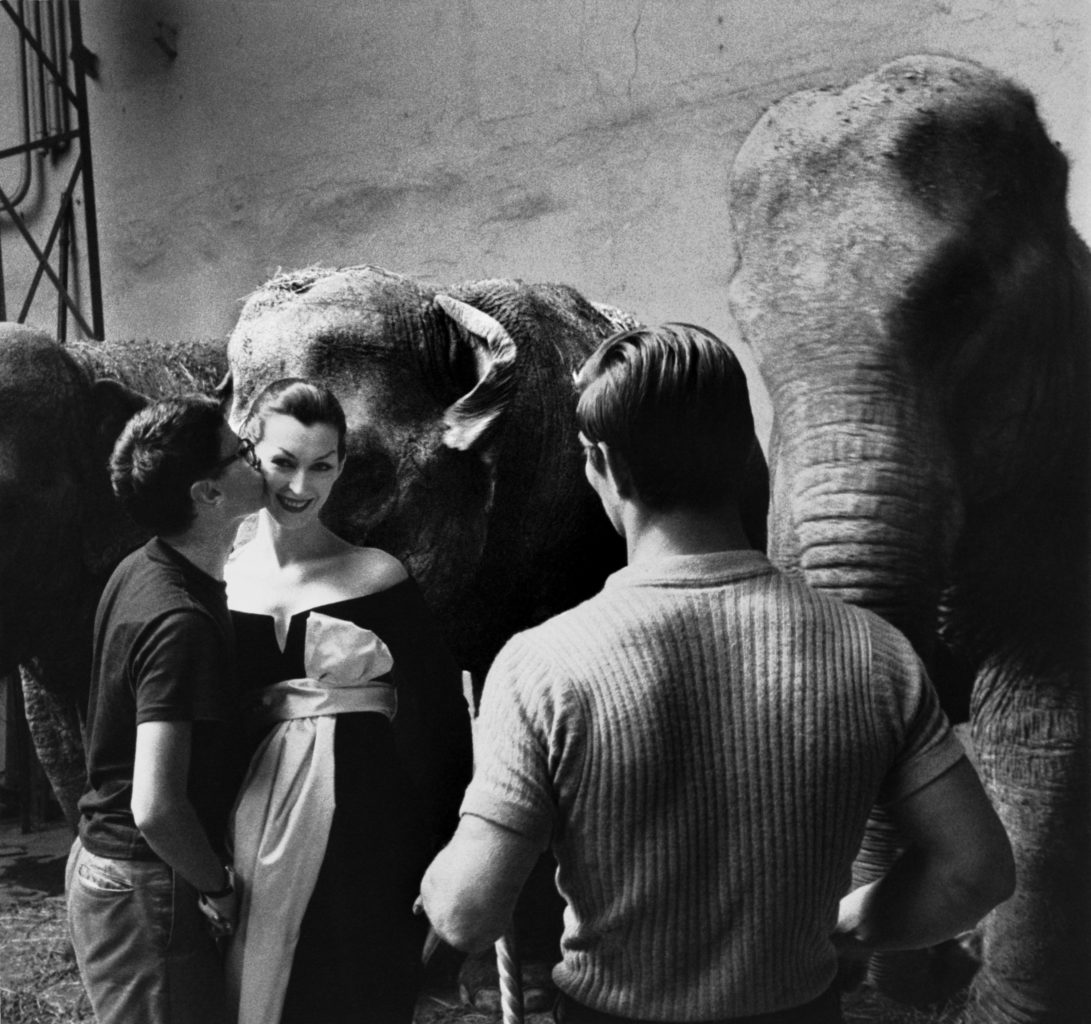

Avedon with Dovima following the shoot at Cirque D’Hiver, Paris, 1955. Credit: Sam Shaw/Sam Shaw Family Archives

Avedon with Dovima following the shoot at Cirque D’Hiver, Paris, 1955. Credit: Sam Shaw/Sam Shaw Family Archives

Dick may have known Sam Shaw through Milton Greene, but it’s possible, too, they first met in the theater community when Dick worked for Theatre Arts. Shaw was a DeWitt Clinton graduate, albeit ten years older than Dick, and throughout the 1940s, he worked for the magazines, shooting feature stories of his own enterprise and getting them published, intent on maintaining his independence and artistic freedom.

But Shaw was restless and, in the late 1940s, after photographing and befriending stage directors and actors—Elia Kazan and Marlon Brando among them—and becoming a set photographer during the production of dozens of films throughout the 1950s and 1960s, he would become a film producer himself.

Shaw often conceived the entire publicity campaign for the films he worked on. The day before the subway grate scene, Shaw brought Marilyn Monroe and Billy Wilder, the director, to Avedon’s studio to be photographed for Harper’s Bazaar. Tagging along with them was Hedda Hopper, the gossip columnist, who was powerful enough to make or break careers with her strategic, if often enough nefarious, use of personal information.

She understood the star power of Monroe and loved the screenplay for The Seven Year Itch, a version of the 1952 Broadway play that had been sanitized to pass muster with the Motion Picture Production Code censors. Hopper was intent on using her platform to promote the film and its star.

No one noticed them until Marilyn turned to her friend and asked, “Want to see me do her?”

Dick photographed Marilyn Monroe and Billy Wilder, and Sam Shaw documented the photographic session, as if he were making film stills of the publicity campaign itself. Marilyn is wearing a different white dress from the one she would wear on the subway grate and a white fur stole around her shoulders. She walks around the studio barefoot, since the shot would not include her from head to toe. In Shaw’s pictures you can see Dick adjusting her hair and positioning her stole, laughing with her at times, or looking at her in mock exasperation.

There is a fan on the set, perhaps to create the effect of wind blowing through her hair, simulating motion in a still image. In these behind-the-scenes pictures, it is striking how different Monroe looks when she is not performing for the camera. She is a rather pretty—if indistinct—young woman, but easily becomes “Marilyn” in front of the camera.

Avedon on the set of the CBS TV special, The Fabulous Fifties. Credit: Earl Steinbicker

Avedon on the set of the CBS TV special, The Fabulous Fifties. Credit: Earl Steinbicker

Avedon’s picture of Marilyn Monroe and Billy Wilder appeared in the November 1954 issue of Harper’s Bazaar: Wilder points at the viewer—us—as Monroe, her head tilted back, her face a radiant mask, smiles brightly amid a frothy dazzlement of platinum hair and white fur, appearing to take delight in what Wilder is pointing out—her viewers.

The text identifies Wilder as the director and Monroe as the star of The Seven Year Itch, giving him all the credit for her transformation and slipping in a dismissive description of her in the process: “He is one in the long line of skillful illusionists who have helped a calendar pin-up girl parlay her own not inconsiderable resources into the image of the All-American Good Time Girl.”

In fact, she was the skillful illusionist of her own image: the deliberate construction of her persona is underscored with an anecdote often recounted by Susan Strasberg in which she and Marilyn were walking down a Manhattan street in the mid-1950s, Marilyn in her civilian clothes—jeans, a baggy sweater, and sunglasses, hair covered with a scarf; no one noticed them until Marilyn turned to her friend and asked, “Want to see me do her?”

Simply by removing the scarf, revealing her blond hair, and shifting her body rhythm, the anonymous pedestrian became Marilyn Monroe and, immediately, a rushing crowd surrounded them.

The photo shoot with Marilyn Monroe and Billy Wilder may have been the first time the Hollywood publicity machinery co- opted Avedon’s prestige for its own purposes, even though it was a mutually beneficial arrangement. At this point in his career, Dick was an active participant in editorial choices about who was important enough or interesting enough to showcase for the magazine, and, at the time, Monroe may not have made his cut. Yet this Hollywood publicity portrait coincided with the beginning of Dick’s introduction to the world of Hollywood that would soon enough project him into yet another layer of stratospheric fame.

__________________________________

From the book What Becomes a Legend Most by Philip Gefter. Copyright © 2020 by Philip Gefter. Reprinted courtesy of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Philip Gefter

Philip Gefter is the author of two previous books: Wagstaff: Before and After Mapplethorpe, which received the 2014 Marfield Prize and was a finalist for both the Publishing Triangle’s Shilts-Grahn Nonfiction Award and a Lambda Literary Award for Best Biography/Memoir; and a collection of essays, Photography After Frank. He was an editor at the New York Times for over fifteen years and wrote regularly about photography for the paper. He lives in New York City. www.philipgefter.com