I headed to the couple bottles I kept tucked in the corner of the “good” living room, the showpiece that Claire never allowed any of us to actually sit in. I filled half a glass with Crown Royal, then lifted it to my nose with both hands and let the scent warm my lungs. I topped off the glass with soda water. All them rules about drinking in the morning go out the window once you start working shifts. Hell. I deserved a drink before this conversation.

I caught up with the boys in my basement, watching BET.

“Hey, guys.”

Simon gave me a thumbs-up from his usual spot on the floor, head propped up on a sofa pillow.

“Hey, Mr. Frank.”

Michael and Gabriel nodded to me from the couch.

I lowered myself onto the recliner, setting my glass on the armrest and missing the days when sitting down didn’t require so much effort.

“I want to talk to y’all about the army.”

Simon, cradling his knees between his elbows, rocked himself to a seated position.

“Come on.” Michael tapped Gabriel’s leg. “Let these two indulge their fascist side.”

My sons stood up, and Simon made a play swipe at Michael’s leg.

“No.” I pointed at the remote control and Simon clicked off the TV. “I want you two to stay.”

Michael and Gabriel exchanged shrugs, then settled back onto the couch. I took a breath.

“Most of the fighting I was involved in took place in Cambodia. That probably don’t mean a whole hell of a lot to you guys now. But it meant we fought more NVA than Viet Cong. North Vietnamese regulars. Professionals. Real soldiers, like us.

“The heavy contact went down about ten or fifteen miles over the border. I can count those times on one hand. I was shitting myself with fear every time. I spent that entire year terrified and exhausted. Hell, sometimes the only reason I didn’t make a run for it was because I was just too got-damned tired.” I paused, looked at Simon. “You’d handle it better.” I waved off his protest. “Nah. You would. But there was something else too. Kind of like getting off. Like an orgasm, when you thought you smoked one.”

That last bit was embarrassing. But how do you express it? That war is hell, but at its height it’s also life. Life multiplied by some number no one’s heard of yet.

“Mostly we shot farm animals though. Pigs, chicken, oxen…”

“Why?” Simon asked.

“Some villages were suspected of supporting the enemy. Hell, the only reason I carried my zippo was to burn hooches. I didn’t even smoke.”

Fragile, ancient things, them villages. Without hardly putting our minds to it, we’d decimate even the big ones in a single afternoon. The whole company—a hundred-plus grunts—watching flames take shape on thatched roofs in the midday sun. My nineteen-year-old mind figuring that surely this many people wouldn’t expel this much effort on something wrong, would they? Then the sergeants would form us up, and we’d drag ass on.

Flamethrower heat from them smoldering huts at our backs, women’s screams ringing in our ears, usually without a single VC in tow, and me so fucking exhausted that, as far as judgment went, I might as well have been piss drunk.

“What do you mean, ‘when you thought you smoked one’?” Gabriel asked.

“You could never really be sure.”

I didn’t know shit from apple gravy when I first showed up. Under ambush, I aped the guys in my platoon and sent rounds downrange. Ta-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat. Like the air was alive with lead. Looking back, I’m pretty sure something would have shifted inside me if I’d actually killed someone. I would’ve known. But I didn’t tell the boys that. I didn’t wanna cop outta what I might’ve done.

“My first squad leader was a lot like you, Simon. Dawkins. Terrell Dawkins. Tough motherfucker. All gas, no brakes. Always volunteering to walk point.” I shook my head, smiled.

“Sniper bait. When I first met him, I thought he was nuts.”

I tried to describe Dawk during that first meeting. Sitting on a rock, face two hollow cheeks with a thick nugget of a nose in between, flipping the selector switch on his weapon back and forth between semi and full while staring off into the bush like some crazy Zulu tribesman. Take your average understrength infantry company—one hundred spics, spades, and white trash. Ten shouldn’t be there. Eighty are just targets. Ten do the fighting and, if you’re lucky, one of these is a gotdamned savage. That was Dawk. In a cadre of touched men Dawk’s mania stood out, making him the platoon superstar.

A reality so fucked up that superstition became the only rational system of belief.“Dawk’s theory was that the second man was more likely to get hit than the first. The kind of guy who didn’t get medals, just that deep field respect that mattered more.” I stopped short, reminding myself: no bullshit. “He was a good killer. One of our best.”

“Fortune favors the bold,” Simon said.

“God smiles on idiots and drunks,” Michael shot back.

“I don’t know about all that.” Those two. Constantly tossing quotes back and forth. “In war you learn more about cowardice than courage. That and luck.”

All them crazy superstitious rituals to fool yourself into believing that it wasn’t just random. Always volunteering for point. Only smoking on every second break. Never walking in tank tracks. Anything to convince yourself that getting smoked depended on more than just ending up fifth in line on patrol, or where you took a dump, or when you noticed that your bootlaces were untied. War didn’t give a shit if you were loved by many or not at all. Charlie was greasing three hundred GIs a month in ’71, and every one of their mommas had told them they was special. A reality so fucked up that superstition became the only rational system of belief. It just so happened that Terrell’s crazy-ass superstitious rituals gave that motherfucker the confidence to stalk the jungle like an immortal. Boys like Terrell—and Simon—don’t need much convincing of their immortality. In my experience, that type fears cowardice more than anything that might actually kill them.

In the bush, Dawk spotted loose soil, crushed foliage, and catgut trip wires. He heard the unnatural silence before an ambush as if possessed of some deeper understanding of these people clawing for survival. Still, on some level we all musta known that part of it was just dumb luck that kept us from getting hit when Terrell was on point. But the fact remained: the men of Third Platoon–Bravo Company–First Cavalry Division didn’t get hit when Dawk walked point. Never. Not once. Even on patrols a good ten, fifteen miles into Cambodia. The heart of Indian country. So far out that we was resupplied by mermite cans kicked out the side of a Huey.

“Dawk was already in his second tour when I showed up in the summer of ’71. He had something to prove. Usually that made guys dangerous. But not Dawk. I think deep down, Dawk wanted to challenge all the things white boys had been telling him his whole life. He reveled in how them white boys feared, respected, and required his ferocity—out there in the bush searching for something only he wanted to find. After he made staff sergeant, he bucked for a third tour. When my year in country was up, I rotated back to the States and spent the rest of my enlistment at Fort Hood handing out basketballs at the base gym.”

I licked my lips and took a sip of my Crown and soda.

“Terrell and me used to talk a lot about Black Nationalism. How the war in Vietnam was going to change everything for the black man in the United States. He once asked me what niggers had done when they returned from America’s other wars.” The boys winced. I guess that word grated outta my mouth, but not Tupac’s. I plowed ahead. “They’d kept on being niggers. But this time it was gonna be different.”

But you best believe I told my boys about that lynching. In the basement that day, I told them boys to love their country.When I was Simon and Michael’s age, almost everyone I knew was black. Lieutenant Nic Voivodeanu, the Third Platoon commander, had been my first white friend. Well, as much as a second lieutenant could be a PFC’s friend, anyway. One time in the mess hall in An Khe, Nic spotted me in the middle of scratching out a letter home.

“Who’re you writing to, Mathis?” Nic asked.

“My mom, sir.”

I returned to my letter, but felt the LT still there, examining the top of my head.

“Sir?” I asked, looking up.

“How old are you, Mathis?”

“Nineteen, sir.”

Nic grinned. “I bet your parents are proud.”

I didn’t say how, before leaving for boot camp, my mom made a point of telling me about the battered, castrated body of a black World War II vet swinging from a yellow poplar in her neighborhood back in Tennessee.

“They’d stripped off his uniform before stringing him up,” my mom said. She talked about the racism of those days—the everyday terror—without bitterness or self-pity. That’s just the way things were.

Nah, I didn’t tell my West Point–educated lieutenant that. Instead I nodded and returned the LT’s smile. But you best believe I told my boys about that lynching. In the basement that day, I told them boys to love their country. It’s the only one we got. You better love it, try to make it better. But don’t ever get caught acting like it can’t happen. It did. It does.

Nic couldn’t understand the rage of the flip-flopped men tracking our platoon in the bush, still less those flip-flopped men’s perfect comprehension of us black draftees marching for an empire that didn’t want us. The same way a kid like Measmer couldn’t see himself pulling a shank on someone like Nestor. They see gooks and cons, where I see men with identities shaped around survival. Men like me, only more desperate and maybe, just maybe, more brave.

__________________________________

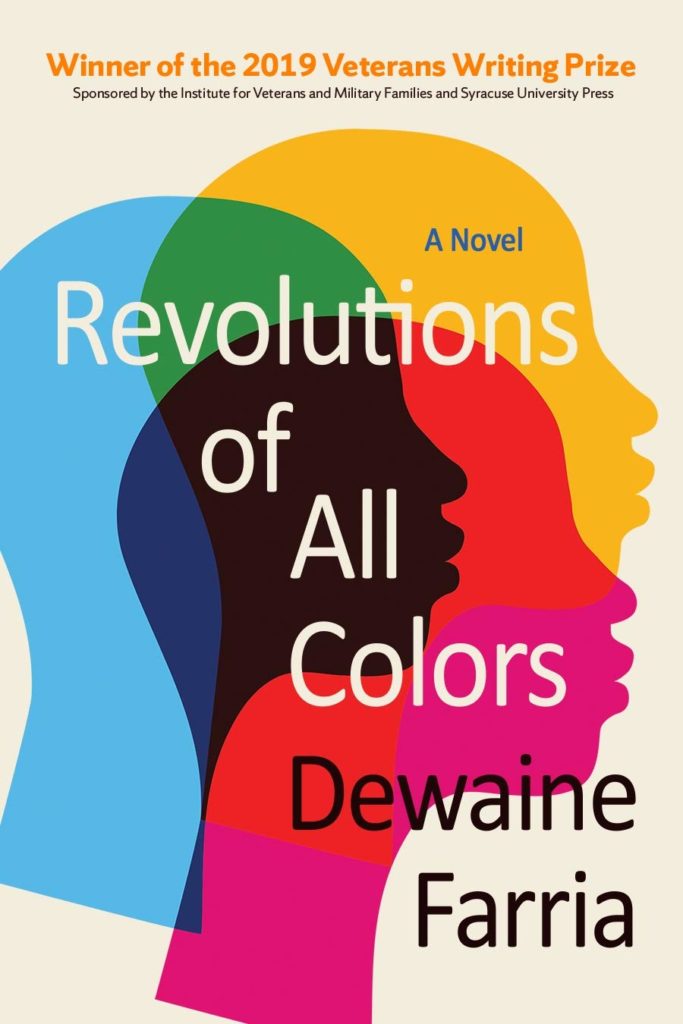

Excerpted from Revolutions of All Colors by Dewaine Farria. Excerpted with the permission of Syracuse University Press. Copyright © 2020 by Dewaine Farria.