When the power goes out, we hang knives from the ceiling as substitute lights; when our beds are hungry, they bake us into bread; when the bills arrive as a flock of carnivorous birds that threaten to peck out our intestines, my mother and seven aunts and I share two bedrooms and rent out the basement—what had once been a slaughterhouse, with hooks that snagged on our shadows and no windows but our mouths—to a series of widows who respond to our Craigslist ad.

The first widow came with a collection of wigs—colored to match any weather, any cloudmood—and refused to use the toilet, saying that she once knew a woman who drowned her baby in a toilet. Instead of using the toilet, the widow pissed into quince-tea jars and shat in a series of Nordstrom Rack shoeboxes that she duct-taped, saran-wrapped, and then buried in our backyard.

The first widow sleepwalked, and one night I followed her to our bathroom, where she stood hook-spined over the toilet and wept into it, attempting to flush down her own hands, which resulted in the toilet being clogged, which resulted in my aunt calling the plumber, who extracted the widow’s stuck hands with a pair of oversized pliers.

Years later, I read that a European euphemism for excrement is nightsoil, and for months I would repeat it to myself, nightsoil, a memory of the first widow walking up from the basement with a shoebox swaddled in her arms, the way she would dig a grave for it and go back to her bed with dirtcharred hands, the word nightsoil, nightsoil, as if the sky itself were made of soil and the stars were seeds I had sown.

The second widow was a florist at the corner stand by the church. She sold white carnations at funerals and taught me how to plant tulips at the right time so that they’d open on my birthday.

When the second widow married again, she sewed a dress of stems but forgot to de-thorn some of them, so by the time she reached the groom, her skin was hole-punched, worms emerging from each of the wounds, like the kind I used to pluck up from the sidewalk after it rained and rebury before the birds could eat them.

The third widow was a butcher and said she liked our basement because of the meat hooks, which reminded her of earrings, silver earrings that the house wore when it was ready to get married, and when I looked closer, I saw that she wore earrings that were miniature meat hooks, that her ears were made of mutton.

She liked to point up at the sky and slice it apart with her fingertip, naming each cut of the blue: rump, ribs, hock, hoof. Sometimes she would say, The sun is a meatball, and I would joke by replying, And what is the daughter, and she would look at me and say, The daughter is a cutting board. One morning, my aunts found the third widow hanging from the meat hooks, the flesh of her shoulders balled into fists around the hooks, her feet sparking against the ground, and when my aunts tore her down, we saw that her mouth was open and her teeth were deleted, and when they buried her in the cemetery up on the hills, my aunts said the third widow was never going to reincarnate, because she was buried unwhole, and that she would forever search our house for her teeth.

The fourth widow was younger than me.

As a child, she had been betrothed to another child, but the other child died of rain in the lungs and she outgrew him. The fourth widow knew how to eat glass and showed me by licking down a lightbulb like a lollipop, dissolving it to syrup, her tongue adopting its coil of light, a light we could see even

when her mouth was closed, a light all moths flocked toward. When I tried to do the same, I was too impatient and bit down on the bulb, shards shrapneling my tongue, and when my aunts found out, they evicted the fourth widow, who ate the rest of our lightbulbs out of spite, so that that night when we turned on all our lights, the house stayed the color of our mouths.

*

The fifth widow could brew tea out of anything: leaves from our trees, trash from the gutters, newspaper, pages of the Bible, toenails.

This tea will make you holy, she said, while boiling pages of hymns in hot water, telling me to sip slow, to sing each word before I swallowed.

Once, she offered to cut my hair, and the next morning she was in our kitchen stewing the strands into ink, telling me to drink, and when I took a sip, I could taste everything that had ever touched my head, rain, my aunt’s sweat, the sky, light.

The sixth widow was hairless and wore a silk scarf she’d bought a decade ago in Xi’an, a blue scarf that looked like the surface of a swimming pool, wired with light.

She told us that she had no hair because years ago she’d fallen into a dream, a dream about being an anglerfish in an ocean that was upside down, like the sky, and growing out of the top of her head was a lantern that lit her way.

She’d been dreaming so deep, her husband thought she had died and sent her away to be cremated, but the crematorium was unable to burn her body, possibly because she was composed of metal and glass, her body orchestrated from air.

The only part of her that burned was her hair, which never grew back, and her husband died a year after her failed cremation, having been hit in the head by a falling beam at a construction site for a mall in Orange County that imposed a dress code on its shoppers: no sweatpants, no T-shirts, only dresses and heels. After his death, she wore only dresses and heels, even to sleep, and at night we heard her walking up the stairs of the basement, calling to her husband to look up look up look up.

The seventh widow was a tailor who walked around the house with a pair of scissors, trimming and re-hemming the curtains, sewing my sleeves tighter around the wrist while I ate, her needles like insect legs, scuttling around the room when she didn’t hold on to them.

My mother brought her wedding dress to the tailoring widow, asked the woman to let it out so that I could wear it when I was grown, but the tailoring widow looked at the dress—red, collared—and then at me and said, This one won’t wear a dress.

I wanted to be the boys in the neighboring house, with their hair done blunt as blades, the way they whetted their legs on everything, the way their sweat dried into rust, and I wanted to run with them as they chased the girls and grabbed at their skirts like reins and yanked—

The girls chased them back, chased the boys with branches found on the street, threatening to shove them up their butts until the branches broke inside them and quilled the insides of their bladders, which was not anatomically correct, and nobody cared, and I was the one who kept changing sides, who kept going back and forth between being a girl and being a boy, who decided finally on being a shadow.

Impersonating shadows, I had to run as close as possible to the boy or the girl without their noticing—I had to imagine myself flat, like a night that had not yet been given legs, like a sea without any blue to buoy it.

The eighth widow was lucky at everything: lottery scratchers, slot machines, sons (she had seven of them, all of them living in the basement with her, though we didn’t know until later).

The eighth widow lived off her luck and did not work; the eighth widow taught me to scratch at the lottery numbers with a penny and never my nails; the eighth widow taught me how to play blackjack; the eighth widow taught me the suits and what they meant: King means husband, queen means wife, spade is the shovel she buries him with.

Every week, the eighth widow snuck another of her sons down into the basement: She told us she only had one, but every week we heard a new voice boiling out of the basement, and for weeks we thought the one son was speaking to himself, until one day we caught all seven of them in the kitchen, eating the oranges off our shrine, and my mother beat each of the boys with her back scratcher and told the eighth widow not to come back.

The eighth widow offered my mother one of her sons if she allowed the rest of them to stay, but my mother said, I have a son already, it’s just that my son is my daughter.

We pray to a god who is a girl in some countries and a boy in others.

I am trying to become something called a resident alien, which means I will be related to my television screen, to all the movies about little green men with heads like testicles, to all the movies about octopi who swim the sky, to all the movies about giving birth to another species, a baby that cannonballs out of your chest and kills you for your name.

Sometimes I pretend the widows are aliens from different planets, that they each adhere to their own gravity, and that is why the ninth widow floats instead of walks, and my mother loves her best because she doesn’t get our carpet dirty.

The floating widow has pigeons for feet, and she sits crosslegged in the basement and feeds them seeds, nuts, spools of thread, crickets, wads of mantou, hair, balls of newspaper that expand in their bellies and teach them the speech of politicians.

The floating widow’s pigeon-feet are very politically active and shit only on gentrifiers in the neighborhood, such as the man who goes jogging even when it rains—when he looks up, the floating widow is clouding overhead, her pigeon-feet shitting into his mouth.

I prefer living in basements because there are never any windows, the floating widow says, because my bird-feet will fly into windows and die, and then I’ll have no way to leave or go anywhere.

The tenth widow wanted to live in a tent in our yard instead of the basement, mainly because she was interested in moonwatching, which she told me was not the same as just looking at the moon—moonwatching was the process by which you wooed a woman down from her night perch.

To woo the moon, you first have to threaten to gouge it out of the sky.

This can be done with chopsticks, a fork, tongs, anything with an end.

When the moon begins to fold itself in fear, you reach your hand out and make a fist around it—quick—the way you catch a knife as it falls—

When the moon is your fist, you teach it who to hit, what to light alive, how to wring the milk out of a man and curdle it into a crescent.

When the tenth widow opens her fist, the moon scatters like a flock of moths.

My mother once told me that every moth is the soul of someone lost and that’s why you’re not supposed to kill them. That’s why there are so many. All our clothes grow holes in the knees, the breasts. Our nipples stick out like snouts. In the closet, our clothes swing like sides of meat. The moths are light-carnivores. I try to catch them alive, to close my fist around their onioned bodies, but I end up crushing them. They blur into the dirt, shunned into dust.

The eleventh widow was not a widow—her husband was not dead but locked away in the correctional facility on 11th Street, and we only found out from the letters she wrote him, which were written in some kind of code that only the two of them could read.

Out of jealousy, my aunts burned the eleventh widow’s letters before she could send them, but the eleventh widow had them all memorized, and the next morning they were written on our walls, a hundred synonyms for husband, all of them meaning missing.

My aunts said it was unfair for some people to own a language that could not be sold to others, a language as private as the blood inside our bodies.

When I asked the eleventh widow what her husband had gone away for, she said, Beating me, and when I asked her if she loved him and why, she turned away and continued writing on the walls.

She taught me how to write my name in her two-person language, which was now marrowed inside the walls, which was now ours. At night, wind ribboned around the house and slid through the leak in the ceiling, learning the language inside our walls and teaching it to the birds.

The twelfth widow was pregnant and told me stories of how her mother-in-law tried to force her to abort the baby by swallowing paper clips, a whole box of paper clips, because the idea was that they would snag on the fetus and drag it out of her body.

My mother says: Some mothers are fishhooks—they’re shaped to raise you, raise you out of the water for slaughter.

My mother’s mother caught fish for a living and sometimes sent foam packages with frozen fish shipped internationally, and the fish never went bad, not even after so many days in the air, a miracle none of us tried to name.

The thirteenth widow once worked as a whalesong writer, said she wrote whalesongs and recorded them on her phone and replayed them for whales, who learned the lyrics and sang along and popularized her songs.

Half of the world’s whalesongs are written by me, she said, claiming she’d spoken in whalesongs for the first half of her life, that her parents had found her in the belly of a whale, a baby like a tumor on its underside, and that some scuba diver must have made love to the whale and impregnated it.

Because we are far from whales, when the thirteenth widow sang, nothing came, only lizards from the gutters, only mosquitos from the trash creek, only professional whale watchers who believed we were harboring a whale in our basement.

Once, the basement flooded and my mother and aunts ran around the house with buckets, trying to scoop out the water faster than it could rise, and the thirteenth widow did not run from the flood.

She ducked her head under the water and swam down, and when the water finally drained out, warping the floors into mirrors and the walls into baloney, we could not find her, not even after we pulled the floorboards up to search.

The fourteenth widow taught me how to tie knots around my wrists and get out of them.

When I asked her what was the point of tying the knots in the first place if I was going to get out of them, she told me it was practice for being kidnapped.

The fourteenth widow had never been kidnapped, but she kept a manila folder with newspaper clips of kidnapped girls and what kinds of knots had been found at various crime scenes.

The knots, she said, the knots are the only thing I can teach you to undo:

One knot was around my ankles and I got out of it with my canines—she taught me to gnaw on bouncy balls for practice, to tune my jaw into a tiger’s, to hide a razor blade in my cheek. The next line of defense, she told me, is to ascend. For example, I have a cousin who’s a cloud. One time, her son put his hands around her neck and all he could wring out was rain.

The fifteenth widow stole my mother’s jewelry, the jade bangles I once thought big enough to wear as collars, the wedding gold that was going to be my dowry, the rings we won at the arcade, plastic with a light embedded inside a fake jewel that only turned on if you bit down on it.

Months later, my uncle saw the fifteenth widow pawning all the jewelry in Reno, saw her with a man, and that’s when we learned she wasn’t a widow at all.

The sixteenth widow loved hummingbirds and hung a feeder in our yard, told me that her father had reincarnated into one and that was why she fed them, in case one of them was her father.

When I asked her how her father had died, she said, Of thirst, told me that some men who had mishandled their memories could no longer even recognize their own thirst, so you had to trick them into drinking by soaking slices of bread in water and hand-feeding them.

If we stood very still with our palms full of sugar water, the hummingbird would drink from our hands, and I could hear their wings dicing up the air, could see the red feathers flirting on their chests like blood from a slit throat.

The seventeenth widow worked for years as an exterminator, and in the summer when the ants came, she sealed the space between our walls and the floor with duct tape and sprayed down our whole house with what we later learned was her sweat.

The seventeenth widow told us her sweat was acidic, her spit too, and that was why she had dentures at the age of twenty-five: Her own spit had churned her teeth into foam, and she couldn’t even swallow without searing her throat.

To dilute the acid in her spit, the seventeenth widow swigged from a smoothie of baking soda and water, said she was trying to become basic, said that the only time she had kissed a man, his molars dissolved and later his tongue required skin grafts from his ass.

One time I asked the seventeenth widow to spit in a jar for me.

I kept the jar beside my mattress, saw it light up in the night, her spit incandescent as the inside of an apple.

Later, I stirred a tablespoon of her viscous spit into my bathwater, wanting to know what it was like to burn, and when I got out of the shower I had no more hair anywhere and my mother saw me and said I’d gone bald as a peanut, bald as when I was born.

I sold her acidic spit to the girls at school as a form of bodyhair remover, and when they asked what it was, where I had bought it from, I said it was imported from Japan and that the spit was the gel of a squeezed leaf, born from a tree that grew without a shadow.

The eighteenth widow broke in and stayed in the basement for two weeks before we found her uprooting our floorboards, claiming to be looking for gold that the previous owner of the house had left her.

Before this house was our house, it was a horse ranch.

Sometimes, if you stood outside the house and looked in, you could see saddles floating through the living room, never any horses attached to them.

Horses were butchered in the basement and hung on hooks, because their meat could be canned and resold as anything: dog food, luncheon loaf, steak.

The nineteenth widow told me that it was possible to bleach your irises blue by looking at the sky too long, so that’s what we did together, skywatch, skylick, waiting for the blue to infiltrate our eyes and develop them into a doll’s. At first, I didn’t want blue eyes, because they melted fast as ice, and it’s impossible to see with only water in your sockets, but the nineteenth widow said a girl with eyes the color of sky would be able to read the weather early, see storms before they arrived, set loose her limbs as lightning.

The twentieth widow had been a beauty-school friend of my mother’s, and she had eyes with white pupils, moving like maggots.

She said this meant she could see the dead—not only dead people but the spirits of roadkill too, and wherever she went she wept for them, the possums that we ran over while they were pregnant, steamrolling the babies inside them into porridge.

When she slept in the basement, she could see the bodies of horses hanging from the hooks, and she said she couldn’t bear it, seeing their hooves off the ground like that, galloping on air, going nowhere.

The twentieth widow was newly a widow: She said her husband had died in a war, though she couldn’t remember which war, only that it was fought using weapons that were wielded by the tongue—miniature knives and bullets that had to be spat—and he finally died one night after biting off his own tongue and releasing it alive in a river, where it became a freshwater eel.

When I asked to see a photo of him, she pointed at her own face and said they’d looked alike, so alike that even her own parents believed her husband to be their son, though they had never had a son and still wanted one.

My mother had a son before she had me, but he was raised by my grandparents in another country, and sometimes he emailed us photos of himself in his military uniform, his smile pieced from shark teeth.

There was a man who lived on the train tracks who had once been in a war, and sometimes he liked to smoke with my mother and tell stories about a horse he had seen in the field where he was born: It was pregnant and dead, and when he slit open its belly to save the baby, a human toddler waddled out into the soil.

The twenty-first widow had three birthdays a year but wouldn’t let us sing to her once.

She said that she’d been born three times: first as a cocoon, then as a moth bursting out of the cocoon, then as a child shrugging out of the exoskeleton.

When she lifted her arms above the kitchen sink to shave, moth wings unfurled from her armpits and tried to fly her away.

The twenty-second widow I was in love with.

She wore her hair in one braid that was long enough to belt around the city, and I liked to loop it around my waist and take it to bed, light it like a wick between my thighs.

One night she reeled in her braid, tugging me down into the dark of the basement, tutoring my tongue into subterranean shapes, fish or fishhook. When she departed one day to become a nun, she cut off her braid and left it hissing on my bed.

The twenty-third widow grew pomelos the size of her ass, teaching me how to skin off the rinds with my fingers so that I could suck out the meat inside and swallow it bitter.

I planted the rinds in our yard and nothing grew, but all the crows gathered around the rind-grave and buried themselves there.

In the spring, our tulips hatched and I dug up the crowbones, strung them into bracelets and wore them around my wrists, ringing the bone-bells of my hands.

The twenty-fourth widow was a jeweler who taught me how to tell fake pearls from real ones: by grinding my teeth against them and feeling the grit of salt, the give of it—counterfeit pearls, she said, are smooth, pirated by girls in factories under the sea, factories where daughters are sanding their own teeth into perfect spheres and selling them.

I held up my fist and ground my teeth against the knucklebones, but they were smooth and not gritty, which must mean I’m fictional.

The twenty-fifth and twenty-sixth widows were twins who had been born three seconds apart, and sometimes they spoke at the same time but in different languages, a way of confusing any interrogators or police officers. There was a rumor that years ago they killed each other’s husbands and ate the corpses to erase all evidence, and just in case it was true, my mother demanded X-rays of their stomachs, which tattled on their contents: cutlery, stray cats, and bones too small to belong to any man.

The twin widows began weaving silk scarves around the hooks, knotting them again and again until they became cocoons dangling down from the ceiling, gnarled and pearl-round.

When they left, my mother tried cutting down the cocoons they’d knotted, but nothing could cut through their silk, not even garden shears, not even meat scissors.

The cocoons rotated on their own, scarfing the shadows around themselves, feeding on mold and sweat from the ceiling. One day I walked down into the basement with a baseball bat and beat the cocoons until they ripened, unseaming to reveal women inside, all of them born widows, widows with translucent skin and eyes broad as palms, praying open.

I opened every window in the house and begged them to leave, told them they were finally free, but the widows never woke: They hung there in the dark, molting into wind, playing their bones like flutes.

__________________________________

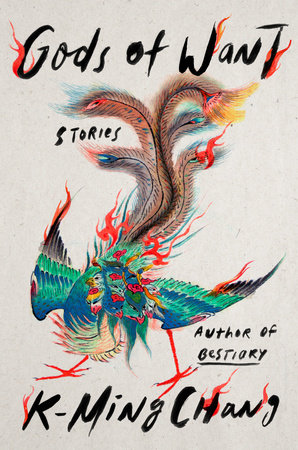

Excerpted from GODS OF WANT Copyright © 2022 by K-Ming Chang. Used by permission of One World, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.