Rescuing the Treasures of a Dead Jazz Legend

Sun Ra, Alton Abraham, and the Taming of the Freak

By the time I stumbled to the phone, the machine had already picked up. “Rise and shine, sweetheart,” crowed a chirpy electronic voice. “Day’s getting old!” I interrupted the message, the receiver’s hovering proximity to the transmitter instigating a brief convulsion of feedback, before switching the answering machine to “off” and murmuring hello to Vic. “It’s now or never,” he said. Still dazed, dopey from painkillers, I forced out a question: “OK, wow, that’s kind of a big surprise, so what’s the plan?” Vic seemed to have been awake for hoursand mainlining caffeine. He spoke with flickering intensity: “Today is anything-can-happen day. Be ready to go in 20 minutes. I’ll pick you up at your place.” I registered assent. Vic punctuated the call’s end with: “We ride!”

It was just after sunrise on a warmish September morning. I was decked out in Chinese silk pajama bottoms. Pulling them out by the elastic band in front, I examined the gauze pad, which had seeped a little with blood and pus in the night. Slipping into a T-shirt and tennis shoes, I splashed cold water on my face, kissed my sleeping wife, grabbed the vial of drugs, and set out for points south, the far South Side of the city that hugs the contour of the lake, into a neighborhood I’d never seen, the home of a man I’d known a little, about a stash of historically invaluable stuff he and I had once discussed. He’d been dead for more than a year.

Three months earlier, on a griddle-hot July afternoon, I’d been sitting in my un-air-conditioned home office, tooling around on email, which then took what now seems an unacceptably long time to load. Among the new messages that oozed its way onscreen was one interestingly headed: “Emergency!!! Sun Ra’s Home in Peril!!!!” It had been forwarded twice, once from the bassist Mike Watt, bassist of fIREHOSE and the Minutemen, and then from an acquaintance of mine who knew about my abiding interest in Ra. The email’s source had been shed in the process of forwarding, but its contents gave a few details: Sun Ra’s home in Chicago was being vacated and all his possessions were being thrown into the trash; could anybody help?; if so please write back to Mike. Somewhere in the message, the sender mentioned a film festival and her own name, which was Heather.

It wasn’t Ra’s house. I knew that because he’d left his Chicago apartment in 1961. But the hidden meaning of Heather’s message was clear to me. Alton Abraham, Ra’s first major supporter and his manager in the 1950s and 60s, continuing piecemeal for decades after, had died nine months earlier. It was Alton’s place. I remembered having thought to myself at the time I heard of his death about the mountain of materials he’d told me about—instruments, writings, tapes, documents. I had suggested finding a place to safeguard and archive these precious objects, and he agreed, charging me with finding the right institution. I’d made inquiries, tried to interest the few folks I knew who worked in those sorts of places, but got nowhere. Funny to think from this vantage, but a houseful of Sun Ra ephemera was not, in 2000, considered culturally significant enough to merit the cost of being stored.

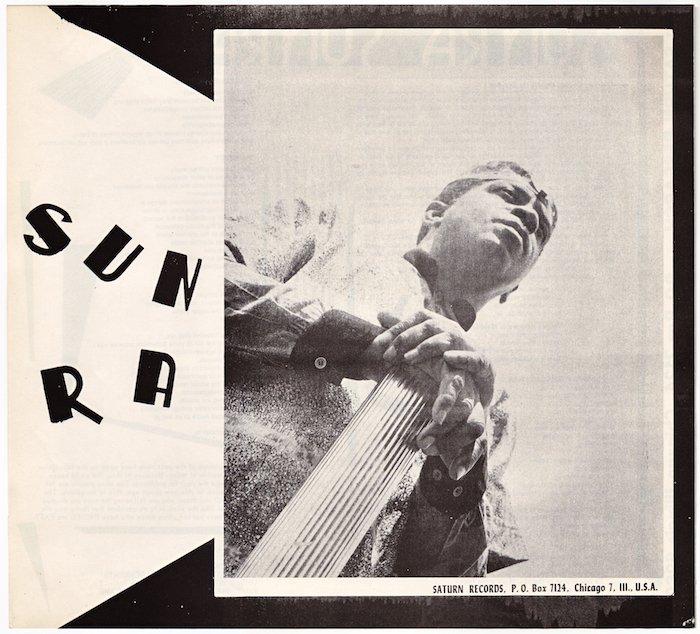

Cover design by Claude Dangerfield, c. 1958.

Cover design by Claude Dangerfield, c. 1958.

Alton’s death gave me pause to think about the fate of these things. After consideration, I decided that there were plenty of people to attend to them, someone certainly would, if nobody else then Abraham’s loyal sidekick, James Bryant. So I let it drop. These months later, sweating onto my keyboard, once again I had the same thought: surely there’s somebody working on this already, at least from the thousand people who must have gotten the Watt S.O.S. My fingers assumed position to delete the email. But just before I let them follow through, I was seized with doubt. What if nobody’s on it? What then? Where will all that shit land? I reopened the message, jotted down the name Heather, and dialed the office of the Chicago International Film Festival.

A few moments later, I was speaking with Heather. She’d only sent the email to her friend Mike half an hour earlier, and I was the first one to contact her, so she was flustered and a little wary. I briefly introduced myself, told her that I’d written about Ra, had spent some time with him on several occasions. She asked if I was free that night, said that she was busy with work. I said yes. “Meet us at the California Clipper,” she said.

“Us?” I said.

“Yeah, there’s three of us. Can you be there around eight?” We agreed and hung up. I thought for a minute about the insane speed of today’s information superhighway, some idea like that, long since made quaint by the hyperbolic curve that technology’s speed has followed in these intervening years. Amused, not thinking too much of it, I went about my day.

*

The California Clipper was dark and empty. A brown bar-back with ornamental detail occupied one side of the space, and a small stage with red velvet curtains sat unused in a corner. I arrived first. After a short wait at the front of the tavern, the door swung open and three young women stepped in. One introduced herself as Heather. The others gave their names, and we wound around to a rear booth, the three of them setting up on one side, me on the other, like a tribunal. I had not noticed the banker’s box carried by one of the women, but after a slightly more involved round of introductions, Heather pulled something from inside the cardboard container at her feet and said: “What can you tell us about this?”

Cover design by Claude Dangerfield, c. 1960.

Cover design by Claude Dangerfield, c. 1960.

It was a shallow wooden block with a swath of metal affixed to one side. A print plate. I felt its weight in my hands, spelled out the words backwards, controlled my excitement, and said: “This is what they used to print the record cover for Other Planes of There, which came out in the mid 1960s.” I put it down. “I know you think this comes from Sun Ra’s house, but it doesn’t. If you look, you’ll find some of what you have has the name Alton Abraham on it.” The three women looked incredulously at one another; one reached into the box and put an envelope on the table.

Heather said: “How’d you know?” I examined the envelope, which was addressed to Abraham, the return address: Sun Ra in New York City.

“I knew Alton. He passed away awhile back. They must have sold his house.” They pulled more items from the box and I identified them and gave a little lecture on each one, puffed up with the thrill of the moment. A note from Ra to Alton discussing possible record covers. The original drawing for the cover of Discipline 27-II. Assorted sketches with Ra and the Arkestra spelled out on them. A couple of record covers with space themes. I remembered the last meeting I’d had with Abraham, at Valois, the diner in Hyde Park with the greatest motto: “See Your Food.” We had chummed around talking nonsense as if we’d been buddies—his voice so deep and cavernous it seemed to come from somewhere inside his large frame rather than his throat. I sensed a longing for camaraderie that might not be so alien to the predisposed loner.

“This is so incredible. You don’t know how outrageously important this stuff is,” I said, returning to the print block. “It took me five years of hunting just to find a finished copy of this record with an offset cover, and then I had to pay 200 dollars for it, it’s that rare. And here we are looking at the printmaking device that they used to hand-make the initial pressing in Alton’s makeshift basement facility.” I straightened up. “The history of DIY music production, the lost early logbook of the most important jazz big-band leader since the 1960s, one of the great visionary artists of all time. This is the root of it all!” The box emptied, we sat looking at its contents as a delayed round of drinks finally arrived.

Flyer, El Saturn Records, Chicago, 1960s.

Flyer, El Saturn Records, Chicago, 1960s.

“A friend of mine is a picker,” said Heather. “He knows everything going on demolition-wise on the South and West Sides, and when something’s being torn down or emptied out, they know where to find him. He got a call to salvage this place, but there wasn’t anything valuable in his eyes, no modernist furniture or cool old fixtures, so he declined. Knowing that I liked spacey stuff and weird kitschy images from the 1950s, he bought a handful of things from them and gave me my pick of the litter. I saw it and flipped out because I knew it was Sun Ra and I knew we had to save it.”

Heather sipped her drink and one of the other women spoke. “We sent out the email, and here you are, as if we had called you. Or sent up smoke signals.”

“What do you intend to do with it?” I asked.

“None of us has the expertise or inclination to do much of anything with it. That’s why we went looking for the right person. Seems like you’re the right person.”

“I would be honored. The main thing would be to keep the bulk of it together. Break it up and each part doesn’t mean as much. I’ll pledge to do right by it, whatever that ends up meaning.” I leaned back, contemplating the most outrageous single acquisition that I would ever make with an unwarranted sense of circumspection. I still had no idea where this would go. I was pleased that I had not hit delete.

Heather selected a single object from the pile and said: “I want to keep one thing. Nothing too important, but a souvenir to remember this.”

Sensing the end of the inquisition, the third woman moved to my side of the booth and proposed a toast: “To Sun Ra, wherever he now resides.”

*

A few days later, I was in Vic Biancalana’s backyard. Mats Gustafsson, the Swedish saxophonist, friend, and fellow record fiend, was in town for a gig, and he accompanied me on the visit. After hellos, during which we learned a little more about our host’s work, including his greatest prize, which was vintage stained glass and historical terra-cotta, we retired to Vic’s garage, where he storehoused and assessed his scavengings.

I liked Vic at once. Shortish and solid in stature, he was coarse, tough, charming, and spoke with an unrelenting Chicago accent: a working-class Italian American guy who panned the grounds of the city’s once-opulent-now-destitute neighborhoods as their edifices were crumbling. He had a gentle smile cocked to one side, the genial hustler, and he spoke of things he would sell and ones he might keep for himself based on his wife’s predilections. “She’s the boss,” he said, tongue only partly in cheek. From the lilting way he talked about his job I got a feeling from him that Vic and I were of the same school of thought about material culture. We were both zealots of stuff.

Momentarily distracted by a pile of seven-inch records—Vic offhandedly told us we could have any of them we wanted—we surrounded a big olive-colored chest. “This is what I got,” he said, pulling open the top and revealing a small container full of Ra paraphernalia on par with but more bountiful than the Clipper unveiling. Mats and I rifled through the things, holding back gasps and shrieks as we uncovered more print blocks, El Saturn Records press releases from the 1950s, and a business card for the Cosmic Rays, one of the vocal groups that Ra coached.

“Heather mentioned that you turned down a full-on salvage,” I said. “What are the chances of you reconnecting? You think the house has already been emptied?”

“I drove by the other day and it’s as was,” said Vic. “I don’t know if she got someone else working on it, but I can try to find out. Might not be easy, though. One thing them asking you, another you asking them.”

“How much for everything in this box?” I asked. We settled on a price, I cut him a check and loaded it into my car. Vic said he’d work on being in touch with the woman who was selling the house.

“It’s been sitting there empty for a year, so we may have a little time. But if it’s already sold, maybe they need to be out. We’ll know soon enough.”

Six months earlier, on the racquetball court with my cousin Tim, I had noticed a bulge in my shorts. Ignoring it for as long as possible, I had the hernia diagnosed and fretted about it endlessly, as only a good Eastern European boy can, ultimately by pretending it didn’t exist. By the time of my initial meeting with Vic the little inguinal bugger had become a pest. Weeks passed. I imagined that Vic would call and soon we’d be on a big haul, which gave me a great excuse to put it off. Every few days, I’d check in and he would tell me he was working on it. I drove to his house a few times to look at other scores, some cool Prairie School chairs, a set of terra-cotta lions he’d extracted from the top of a building. The latter he was forced to give up by an alderman who threatened to shut him down if he didn’t put them on her front lawn overnight. The island of misfit toys or the mafia of reclamation—sometimes it was hard to tell them apart.

Wondering about the potential contents of the house, I called an East Coast record producer I knew who had dealt with Alton. He said he hadn’t heard anything about Alton’s place being cleared out. “Anyway, it’s nothing, I’m sure,” he said.

“Nothing? You don’t even want to check to make sure that important historical material isn’t being trashed?”

“Let me make a few calls,” he said. A week later, I called again. “I checked and it’s nothing, it’s shit. Nothing but 40 years of junk, no tapes, nothing significant. Shit shit shit. Nothing but shit, you hear?”

I let his weird rant die out. “Yep, I hear you loud and clear.” I knew four things for certain: 1) it definitely wasn’t shit, there was something important at Alton’s, maybe lost tapes; 2) it was of great historical significance; 3) he was after it; 4) I could never trust that guy again.

However, after six weeks of effective procrastination, I admitted to myself that the likelihood of salvaging the house was dimming and that I should schedule my surgery. Vic said he’d been in touch and they were “considering his offer,” the specifics of which he would not divulge. But still time dragged on and I steadied myself to go under the knife.

My father-in-law was the one person I knew who was experienced in the hernia surgery department, and his advice was not to worry, that he’d been up and at ‘em later the same day. This seemed far-fetched to me, but it gave me courage as I was prepped and shaved and drugged. “Let’s give him a really fun trip,” I remember one anesthesiologist saying to another as the spike hit my arm. “Count backwards from one hundred.” I didn’t make it to 97.

Experiences vary wildly, I learned, and I could barely stand up by the second morning. The second night my penis turned purple and I made a panicky call to the nurse, who said it was normal, happens all the time. “If there’s even a remote chance of this happening,” I grumbled unhappily into the receiver, “then you must tell the patient about it! It’s terrifying. I thought it was going to fall off.”

__________________________________

From Vinyl Freak: Love Letters to a Dying Medium by John Corbett. Copyright Duke University Press, 2017 · Feature image, Sun Ra, NYC, c. 1962 (photo: Charles Shabacon). All images courtesy of the Alton Abraham Sun Ra Archive, University of Chicago Library, Special Collections.

John Corbett

John Corbett is a music critic, record producer, and curator. He is the author of Microgroove: Forays into Other Music and Extended Play: Sounding Off from John Cage to Dr. Funkenstein, both also published by Duke University Press, and A Listener’s Guide to Free Improvisation. His writing has appeared in DownBeat, Bomb, Nka, and numerous other publications. He is the co-owner of Corbett vs. Dempsey, an art gallery in Chicago.