Rereading My Words in the Midst of Profound Grief

Gabriel Bump on His Characters' Personal Tragedy, and His Own

When finishing a novel, there is an introspective sweet spot before publication and after the final edits get turned in, when, in a quiet anxious period, I’m forced to look at my creation, to try and understand what I have done, to remember how this thing was formed. An important question for any journey: what do I think, now that it’s over?

After The New Naturals was edited, typeset, done, I turned to the beginning, back in 2017, before it was a novel, only a bubbling idea inside a young novelist.

At the time, I was living in Western Massachusetts, teaching essay writing at a college near Fall River, about two and half hours away from where I lived, in Montague. I spent three days a week driving along Route Two eastward to my obligations. On these drives, I would cross the French King Bridge, the Connecticut River ambling far below. There was a nondescript restaurant near the bridge. Never busy. White roof, red siding. The French King Restaurant and Motel. I would wonder about the restaurant. What was it like in there? It was situated on a hill. I imagined the spectacular view: down on the river and the lush Pioneer Valley. I never parked and went inside. Wondering was better.

A year later, in a coffee shop in Buffalo, the first pages of this book started with a young man failing and apologizing. That scene still exists in The New Naturals, although slightly changed and halfway through, although the coffee shop is no longer there, replaced by another small chain, I think; anyway, the scene: a young man, Bounce, tries to make breakfast for his girlfriend, fails, is figuratively paralyzed by that small failure placed atop several other failures. The young man breaks down, cries, over burnt eggs.

I wanted to get this sad young man to The French King Bridge. Get him inside that restaurant, let him see what’s in there.

*

I had recently washed up in Buffalo. I was going through a divorce, feeling a shame unique to freshly failed marriages. The humming paranoia, certain that all your friends, family members, and acquaintances are talking about you, wondering what really went wrong, whispering they had expected failure and you didn’t deserve love and happiness, never deserved it. The divorce was complicated by my intensifying struggles with anxiety and depression. This was right before our greater cultural understanding of mental health. I felt alone and ashamed in my struggle. I thought I was weak, soft, overly emotional.

I went to a therapist, struggled to express myself, continued struggling to express myself with friends and loved ones.

Nothing terrible had happened between me and my ex-wife. The relationship wasn’t explosive. For months, maybe years, I was decaying inside. On my drives across The French King Bridge, I had often wondered, what if I parked and jumped into the river, or how fast would I have to drive in order break through the barrier and comet down?

I didn’t jump. I maintained speed. One day I was there. One day I was gone. To Buffalo.

*

I had sold my first book, Everywhere You Don’t Belong not long before I left Massachusetts. My publisher had also purchased a second book. I had cash from the deal to rent an apartment in Buffalo above a coffee shop, as well as cash to help my ex with rent. I would wake up early, read for an hour or so, walk downstairs when the shop opened around seven, drink a small coffee, write five hundred words, go for a run around Elmwood Village, spend the rest of the day figuring out ways to stay alive. Video games, books, the White Sox, the occasional date. I read big books back-to-back: William Trevors’s Collected Stories, Tolstoy’s War and Peace. I wanted to write a big book. A bigger book than my first, with more emotional and thematic sprawl. I figured writing this book might be the last thing I do.

Of course, life got better, as life often does, or I felt better about life. I settled into my routine. Reading, writing, running. I made friends, fell in love too fast, fell in love too fast again, was grateful to feel love again, powerful, grounding. I was grateful for myself, for making it through, for finishing a draft, which had outgrown the initial journey. I got the sad young man to The French King Bridge. I got him there alive. Healthy. By the time he arrived, the book had grown around him, spun into a complex ecosystem with several other characters and missions.My sadness, too, no longer defined me. It was, instead, only a characteristic among other characteristics, right there alongside resilience and joy.

The new first chapter concerned an academic couple, two professors at a college in Massachusetts, Rio and Gibraltar, who find their priorities shifting during the wife’s pregnancy. When their baby girl, Drop, dies unexpectedly, their priorities, once again, shift. They are no longer focused on protecting their daughter from a cruel world. They turn their focus outward, toward all of humanity.

I wondered what rereading The New Naturals would do to my grief? How would I appear in my new perspective?

My novel follows the creation of an underground society funded by a mysterious benefactor, transients ambling across the Midwest towards Massachusetts to get to that underground society, grand missions to halt a crumbling world. The book was big. Not seven hundred thousand words big. Still, big conceptually. Epic.

In less than a year, in early 2019, I had the draft.

*

In Everywhere You Don’t Belong, I wrote as a young man, homesick, in Western Massachusetts, in grad school, writing about his old neighborhood, missing his grandma, his friends, Lake Michigan, Maxwell Street sausages, the complicated desire as an eighteen-year-old to leave a loving home, go to college in another state, venture out into the world, try to mature on your own, the almost looming specter of failure and sadness.

Here I am, in The New Naturals, as you know, different than before, in a coffee shop in Buffalo, working every day, preoccupied with epiphany, finding bits of myself in every character, healing them as I attempt to heal myself, searching, wondering if my characters will find peace, wondering if I’ll finish the book and still want to live.

Here I am now, writing to you, different again, settled, in North Carolina, teaching at a university, inundated with new joys and tragedies, new paranoias, married with two dogs and a bird feeder in our backyard, grieving the death of an unborn child, the worst pain, unbearable, unimaginable.

*

As I worked through final edits, during my wife’s pregnancy, I felt closer to Rio and Gibraltar. I read their scenes with fresh insights. The existential dissociation in academia. The desperation in teaching “The Day We Got Drunk on Cake” to a classroom of, rightfully, bored teenagers wondering why their professor thinks this story is one of the best stories ever written.

I was surprised by the distance between Bounce and myself. I felt for him. I still loved and cared for him. I am still happy about his growth and settling. I was him. Now, I’m not.

*

Rio and Gibraltar and their child, Drop, yet unborn, growing in the womb, taking up outsized space in their everyday lives, influencing all their decisions: I felt that domination. These characters I wrote years ago purely from imagination were now the realest part of the book.

When Drop died, I read those chapters and felt a deep fresh sadness at the possibility of losing our daughter, Simone. No. No. What if that happened?

*

When it did happen, when we lost Simone, when our lives changed, again, morphed, instantly into a walking nightmare, my perspective on this book changed. My lens shifted. I still loved the other characters. Still felt invested in the plot, the arcs, the various transformations. Still, there is only Rio and Gibraltar and Drop. There is only Rio and Gibraltar consoling each other in the days after, the desperate urge to change the world, which presents in their need to form an underground society, a new world, fulfill an idea Rio had when she was pregnant and trying to protect her daughter. Drop’s death had started as a plot device; which terrible experience would be so terrible as to make Rio and Gibraltar devote their lives to this fanciful project, to try and create The New Naturals?

I wondered what rereading The New Naturals would do to my grief? How would I appear in my new perspective? Could I read it and not feel my wife squeezing my hand in a hospital room, looking into my eyes, our baby, Simone, dying inside her, her heart and kidneys failing, her body mostly fluid, her one-pound body, now, creating the possibility of mirror syndrome, preeclampsia, threatening to kill my wife, this baby we have loved more than we have loved anything, now, a bomb against us?

I will never forget the fear of losing them both. I will never forget when my wife and I drove across country, California to North Carolina, purple buttes in New Mexico dusk, the high desert of Arizona looking like mars, the windmills and slaughterhouses across Texas, the rice paddies along the bayou, the mountains of Tennessee, North Carolina, home.

I will, years from now, continue to view my life as a series of long drives, across bridges, across novels.

___________________________________

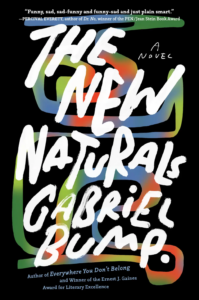

The New Naturals by Gabriel Bump is available now via Algonquin Books.

Gabriel Bump

Gabriel Bump, author of Everywhere You Don't Belong, grew up in South Shore, Chicago. His nonfiction and fiction have appeared in Slam magazine, the Huffington Post, Springhouse Journal, and other publications. He was awarded the 2016 Deborah Slosberg Memorial Award for Fiction. He received his MFA in fiction from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He lives in Buffalo, New York.