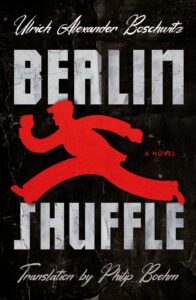

Requiem for Weimar: On Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz’s Berlin Shuffle

Philip Boehm Considers the Contemporary Relevance of a Tale of 1920s Germany

Berlin in the late 1920s was home not only to the flourishing nightlife we know from Cabaret—it was also a leading center of science, architecture, technology, and the fine arts. While Brecht and Weill’s Threepenny Opera was breaking box office records, Albert Einstein was presenting his paper on unified field theory to the Prussian Academy of Sciences. The most industrialized city on the continent boasted a new airport at Tempelhof, subsidized housing projects, and the impressive Berliner Funkturm tower, which would soon broadcast the world’s first television program.

But the Golden Twenties turned out to be not so gilded for the hundreds of thousands who lost their jobs in the wake of the world economic crisis of 1929, sending the unemployment rate to over 30 percent by 1932. Evictions soared, and prostitution, which was already widespread, surged—as did organized crime. Beggars and vagrants were a common sight.

The author’s cinematic structure displays carefully calibrated shifts of perspective…that vividly evoke the vibrant and often violent city that was Berlin.

It is these destitute and down-and-out Berliners who are shuffling through the streets of Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz’s early novel, slowly making their way to the Jolly Huntsman pub, where some come to drink, some to listen to the music, some to dance. There’s the world-weary Fundholz hoping his begging will earn him enough for a little schnapps, and Tönnchen, forever fixated on food. Frau Fliebusch has come convinced she’ll find her husband who never returned from the Great War, while Handsome Wilhelm is attending a meeting of criminal Ringverein. Fritz Grissmann has plans to snag a woman: He starts waltzing with the wife of the embittered blind veteran Sonnenberg…and disaster ensues.

But the disaster on the mind of the twenty-two-year-old author is larger than a barroom brawl. His scenes of conflict between characters “caught under the wheels of life” invite the narrator’s tragically prescient reflection:

“To date, the World War and the Inquisition have achieved the greatest success when it comes to large-scale eradication of humanity. It is to be expected that in the coming years we will experience entirely new episodes of annihilation.”

*

This authorial debut displays the same sharply drawn portraits that characterize Boschwitz’s later novel The Passenger. The rediscovery of that work, as well as this one, is in large part due to the efforts of the German editor and publisher Peter Graf, who learned of the book from Boschwitz’s niece. Graf located the original manuscript of The Passenger, revised it in accordance with the author’s written wishes, and published it to international acclaim. The rediscovered novel is now available in more than twenty languages, roughly eighty years after the author’s death.

Following that success, Graf turned to this book—the author’s first novel, which had appeared in Swedish translation in 1937 under the title Människor utanför (“People outside”), earning the author comparisons to Hemingway. In 2019, Graf published the first original German edition, keeping Boschwitz’s German title Menschen neben dem Leben (“People alongside life”). This translation follows that publication, with some slight additional editing.

Here, as in The Passenger, the author’s cinematic structure displays carefully calibrated shifts of perspective, as close-ups revealing the inner thoughts of the protagonists give way to long shots that vividly evoke the vibrant and often violent city that was Berlin. We hear the din of the city: the rumble of buses and honking of cars whose drivers surge impatiently ahead, heedless of pedestrians. To escape the hubbub, or to snag a little shut-eye, people turn to the parks. But even there we encounter characters full of aggression and resentment—the festering disaffection that would feed the Nazi storm. “It’s all the fault of the Freemasons and the Jews,” rants one out-of-work locksmith.

Berlin Shuffle is a testament both to a remarkable talent and to a turbulent time—a message in a bottle finally retrieved, and startlingly relevant.

Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz was born in 1915 to a Jewish father and a Protestant mother. His father, who had converted to Christianity, was drafted at the beginning of World War I and died of a brain tumor just weeks after the birth of his son. In 1935, in the wake of the Nuremberg Laws, Ulrich’s sister moved to Palestine, while he and his mother escaped to Scandinavia. Other moves followed: France, Luxembourg, Belgium, and finally England. When the war broke out, he and thousands of other German and Austrian refugees were deemed “enemy aliens” by England and were interned on the Isle of Man. Later he was deported to Australia aboard the Dunera alongside hundreds of other refugees—including a grandson of Sigmund Freud, who had been similarly classified. The men were subjected to various abuses by their captors, such as theft and beatings, and many personal effects were tossed overboard. Boschwitz himself lost a manuscript he had been working on. In Australia, the deportees were placed in an internment camp in New South Wales.

Finally, in 1942, the British authorities reclassified the refugees as “friendly aliens,” and Boschwitz was freed. He decided to return to England aboard the MV Abosso, but on October 29, 1942, that ship was sunk by a German submarine, and Boschwitz perished, at the age of twenty-seven, along with 361 other passengers. With him sank the manuscript of a new novel he had written during his internment, which he had titled Traumtage (“Dream days”).

On July 13, 2019, a Stolperstein, or “stumbling stone,” was laid in Berlin at Hohenzollerndamm 81 to memorialize Boschwitz, his mother Martha, and his sister Clarissa, whose daughter Reuella Shachaf was present. In her speech she noted, “It hurts to think how many books were lost by his death.”

The two books we do have only amplify that sense of loss. Like The Passenger, Berlin Shuffle is a testament both to a remarkable talent and to a turbulent time—a message in a bottle finally retrieved, and startlingly relevant.

__________________________________

From Berlin Shuffle by Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz, translated by Philip Boehm. Copyright © 2025. Introduction copyright © 2025 by Philip Boehm. Available from Metropolitan Books, an imprint of Henry Holt & Company, a division of Macmillan.

Philip Boehm

Philip Boehm has translated more than thirty novels and plays by German and Polish writers, including Herta Müller, Franz Kafka, and Hanna Krall. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, as well as numerous awards, including the Helen & Kurt Wolff Translator’s Prize and the Ungar German Translation Award from the American Translators Association. He also works as a theater director and playwright.