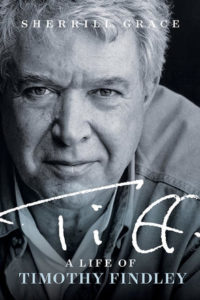

Remembering Timothy Findley on His Home Ground

Sherrill Grace on the Life and Legacy of a Great Canadian Writer

I have returned to Stone Orchard, Timothy Findley’s home, many times over the years of research for his biography, each time learning more about the man who lived and wrote there, but one damp November day remains with me as only a first, impressive experience can. As I walked through the fields, surrounded by the scent of damp vegetation and fresh air—memory inhaled—I could situate Timothy Findley on this, for him, home ground, where he struggled against despair and experienced peace, joy, and great success. I remember that day well. It was November 11, 2011, spitting rain, chilly, with low grey clouds—my first visit to the farm called Stone Orchard, where Findley had lived for 30 years and where he wrote most of his fiction and plays. I knew how important landscape and place were to him and how necessary they were for the biography I would write, and no place was more significant to him than this home.

I was especially grateful, therefore, to the current owners, who gave me a tour of the old house, beginning with the spacious kitchen where Findley often sat with tea or coffee while reading his latest draft aloud to his lifelong partner, Bill Whitehead. The large living room had been renovated, but photographs show that in Findley’s time the walls were lined with books and the room contained two large sofas and his beloved piano. Upstairs there were still traces of the cerulean blue walls that he liked to have around him. (As I later discovered, Findley often said that “blue was the color of hope.”) I was allowed to roam the grounds of Stone Orchard and to explore the fields: there was the old root cellar, refurbished to give him a writing place in good weather; there was the barn that housed so many dogs and horses he and Whitehead rescued; there was the low stone wall running beside the property (within which he had placed a sealed bottle carrying a message for the future); farther off was the pond that they created to attract migrating birds. Beyond the grounds, the fields, now wet from the rain, stretched to distant woods and the Beaver River, places where Findley walked the dogs, landscapes that found their way into his writing and stimulated his imagination. Above all, this place was his home.

His fiction fascinated and haunted me, but I did not know the human being who could write and move me so profoundly. I wanted to know him.

Some of Timothy Findley’s ashes were scattered here in the autumn of 2002, and the ashes of many family members and of his animal “significant others” were also scattered in these fields he loved and in the herb garden he tended. Stone Orchard provides much insight into the person behind the art: a man for whom ancestors, memory, and home were crucially important, a man who achieved so much and yet remained tormented by fear of failure, of rejection, and of dying before he had said all he felt compelled to say.

Timothy Findley (1930-2002) was a celebrated author and an astute witness to Canadian culture and society from the 1960s to his death. He wrote award-winning, iconic novels like The Wars, Famous Last Words, and Headhunter, hugely popular ones like Not Wanted on the Voyage and The Telling of Lies, major historical fictions like The Piano Man’s Daughter, several award-winning plays, and some very fine short stories. He contributed to important developments in Canadian writing and publishing during the 1970s and 80s and was a founding member of the Writers’ Union of Canada. His voice was raised, with passion and conviction, on crucial issues during those years, from war and human rights abroad to environmental degradation and censorship at home. His story is, in no small part, Canada’s cultural story during the last thirty years of the twentieth century, and his life’s path intersected with many major artists of his time, from Alec Guinness, Peter Brook, and Thornton Wilder to Glenn Gould, William Hutt, and Margaret Laurence.

Although I read each of his works as it was published and saw his plays in performance, I never met him. His fiction fascinated and haunted me—it still does—but I did not know the human being who could write and move me so profoundly. And I wanted to know him, to understand, if I could, what shaped this man into the writer and witness he was. This question came to a head in 2007 while I was teaching The Wars. Despite my long-standing appreciation of the novel, I had not yet paused to consider its author or his reasons for writing the book; I had been trained to focus on the text and ignore the author. But the times and critical approaches had changed, and my students were curious, with questions I could not answer.

A few years later I taught a graduate seminar exclusively on Timothy Findley and quickly realized that these students were also swept away by his writing; they were no more than 25 years old, but they became hooked because they saw Findley as speaking to their generation. Again there were the questions: why had they not discovered him before and how could they learn more about the author’s life? In 2010 I cleared my desk and began my search for Timothy Findley, the man, in his time and place. I too wanted answers.

Caveat lector: a biography cannot capture its subject whole; it should not claim to have the Truth or all the answers. Happily, a biographee slips through a biographer’s net, preserving a core of privacy. This is true even for a person like Findley who published two memoirs, kept exhaustive journals (surely intended for his biographer to find), drew on his family’s and his own experiences for his fiction, gave many revealing interviews, and wrote frank letters to close friends. This is, moreover, a literary biography because Findley was a major writer whose life intersected with some of the most fascinating people and momentous events of the twentieth century. What he had to say about his century was important during his lifetime, but it remains relevant—urgently so—today. His advice to himself and to all who read him was this: no matter how violent and dangerous the world becomes, do not give in to despair but pay close attention to the possibilities and joys of life.

To resist despair, he employed creative imagination in his life, and he invited his readers to do the same because he believed that “imagination can save us.” He was often angry with this world, most especially with human beings and with himself; he could be violent when drunk and he drank a lot, but he was also full of laughter and joy. He had fun—enjoying his friends, his family, his garden and animal companions, good food and wine—when he wasn’t working extremely hard to give us the novels, plays, and stories that are his legacy.

The life of a serious artist—painter, writer, composer—is a solitary one, and Findley constantly faced a paralyzing loneliness compounded by his search for artistic perfection. In Bill Whitehead, however, he was blessed with a partner’s love and support, and he knew he was blessed. He was deeply loved by his mother and, eventually, by his father, even though Allan Findley never fully understood him and inflicted lasting emotional scars. Extended family members also provided loving support, as did many close long-time friends through the friendships he cultivated and treasured. He was admired and respected even by those who observed how difficult he could be, and young people who attended his readings have told me that he charmed them because he took them seriously and listened attentively to them. He was, in short, a complex, generous, formidably intelligent, volatile, acutely sensitive person. But in the final analysis, he lived to write and to communicate, and he has left us with his vision of a world in need of our attention, love, and imagination.

In telling his story, I sometimes call Findley “Tiff,” and there are several reasons for this informal address. Tiff, which stands for his full name—Timothy Irving Frederick Findley—was how he thought of himself, and everyone who knew him even a little called him Tiff; in interviews and on other public occasions he was often addressed as Tiff. This name carried important family associations for him. Nevertheless, he was, and still is, the writer, Timothy Findley, and the formal name meant a great deal to him as well. He was also adamant about another form of address: he spoke of himself as “homosexual” and disliked the word “gay.” He resented being called gay, rejected the notion that he and Whitehead were “poster boys” for gay marriage, and vehemently refused to be categorized as a “gay writer.” Nevertheless, his homosexuality must be considered carefully because of the ridicule and trauma he suffered as a young man, the particular social and legal context for homosexuality between 1940 and 1970, and the relevance of these experiences for his work. That said, my primary focus is on his life as a writer, a great one, I believe, who happened to be Canadian, to live most of his life in southern Ontario, and to be gay. His audience was the world; his subject was the human species and other living creatures; and his message was always to maintain hope.

In his review of Otto Friedrich’s biography of Glenn Gould, Findley wrote something that has remained at the back of my mind while writing this book. He warned that “the creation of any successful biography involves, of necessity, encounters with any number of nightmares for a writer: facts that cannot be verified; people you need to interview who die two days before you arrive; intransigent keepers of the flame who refuse to divulge the one vital thing you must have access to” (IM 279). Findley could scarcely have summarized the hurdles a biographer faces more succinctly. Other writers have made similar comments and warned against a biographer trusting their subject’s duplicities, the faulty memories of well-intentioned friends or the skewed perspective of enemies, and the frustration of arriving after a key person has died or finding that vital information has been lost or destroyed. But not all writers are as interested in autobiography and biography as Findley was, as skilled at creating fictional biographers and autobiographies as he was, and as insistent that memory, whether faulty or not, is fundamental to human identity and survival. Moreover, Timothy Findley understood the slipperiness of life stories and made telling the difference between truth and lies a central theme in his fiction.

The truth is—and here I am certain it is the truth—he enjoyed performing, and, as a former actor, then a public intellectual, he was always the consummate performer. Performance was integral to the man and the artist even when, I have come to believe, he wrote in his personal journals. I have had to tread carefully, therefore, through the private landscape of his journals and the public presentation of himself in readings and interviews to detect the person behind the role and to expose the vital capillary links between the two. But this journey has always been exhilarating, with moments of frustration when I arrived at a dead end and moments of delight when I turned a journal page to find an answer to a question, a drawing of cats, a single dried and pressed flower, or a quickly sketched self-portrait—Tiff as the all-night, early morning artist with cat companion and coffee cup and, tellingly, with his back to the viewer.

Finding Timothy Findley has produced all the nightmares he mentions in the Gould review and a few more besides. If I could have interviewed him before he died, I would have tried to confirm certain details. He, of course, might not have answered my questions about his aunt, Ruth Bull Carlyle, and her medical condition or why she meant so much to him, and he may not have known if he had a distant Fagan relative in Ireland who suffered from a mental illness that had been passed down through the generations. I would have asked him about his interest in the writer Malcolm Lowry, in the painter Attila Richard Lukacs, and in the composer Franz Schubert, especially his fascination with Schubert’s last piano sonata. I wish I could ask him if he actually owned a recording of Alfred Cortot performing the piece and, if not, why he invented such a record for Famous Last Words. My reading of his journals suggests that the psychiatrist who subjected him to grotesque treatment in the late fifties was a Dr. Snow, but he may not have been willing to discuss that episode in his life or able to remember how he came to be treated by this doctor. Although he might well have balked at my inquisitiveness, I would certainly have asked him about being persecuted at school and if he was sexually abused at some point in his youth because so much in his fiction suggests that he was. One must be careful, however, not to read the fiction back into the life.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Tiff: A Life of Timothy Findley, by Sherrill Grace, with permission from Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Sherrill Grace

Sherrill Grace is a University Killam Professor Emerita at the University of British Columbia. She specializes in Canadian literature and culture and has published extensively in these areas. Her recent books include Inventing Tom Thomson, Canada and the Idea of North, Making Theatre: A Life of Sharon Pollock,and Landscapes of War and Memory.