Remembering the Unacknowledged Sacrifices of the Red Army’s Female Snipers

Shelly Sanders on the Brave Women Silenced By the Country They Fought to Protect

On a chilly March afternoon in Poland, 1945, Guards Lieutenant Nina Lobovskaya, commander of a Red Army female snipers’ platoon, had orders akin to the battle of David and Goliath: defend a vital section of highway from a large Nazi unit with fifteen snipers. Twenty-one year-old Lobkovskaya, with apple cheeks and a ready smile that belied her determination to kill fascists, had already triumphed in a weeklong sniper duel with a German officer (who was training subordinates to stalk Soviet snipers), and she’d taken part in the liberations of Nevel, Belorussia, and Warsaw.

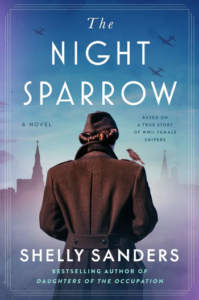

I became fascinated with Lobovskaya while doing research for my new novel, The Night Sparrow, and I wondered why she is not part of the WWII narrative. “Red Army females” were the only women in combat during WWII yet their names and stories have more often than not been forgotten. These women reflect a vital part of history that is vastly different from their male combatants’ point of view. “Everything we know about war we know with a ‘man’s voice,’ wrote Svetlana Alexievich, in her Nobel Prize winning book, The Unwomanly Face of War: An Oral History of Women in World War II. “Women’s’ war has its own colors, its own smells, its own lighting, and its own range of feelings. Its own words.”

As we commemorate the 80th anniversary of VE Day, it’s imperative to give voice to those women who were silenced by the country they fought to protect. We need to add their names and stories to the historical narrative in order to fully see all sides of war.

The female snipers’ identities and achievements, all the gains they’d made in terms of equality, were buried along with the names of those who’d died.

Lobovskaya was one of 2,500 women snipers, with a combined tally of 11,000 kills. The majority spent six months at the newly created Central Women’s Sniper Training School. Vera Samarina, a “frail redhead,” as described in Soviet Women on the Frontline in the Second World War, had a fear of rifles and shooting when she arrived for training. By the time she got to the front, she was ready, shouting, “Let’s get ourselves into gear, stand up to the Nazis and drive them back!” Other women, like Sergeant Roza Shanina, thrived on the action; she wrote in her oil-cloth-bound diary: “I thirst, thirst for battle, the heat of battle. I would give everything, including my life, if only I could satisfy this whim. It torments me….I didn’t go anywhere until dark, and after dark went to Nikolay and quarrelled with him about Lena—my rival from the medical battalion.”

Any concerns about women’s effectiveness in combat were alleviated by General V.A. Yushkevich, in a letter to the Central Women’s Sniper Training School one year after they’d arrived: “The pupils of your school, participating in the military operations of the armies, exterminated 2,138 German fascist monsters…” There were countless newspaper and magazine articles praising the women, too. “Nina Lobkovskaya has a sharp eye and steady hand,” a reporter wrote in a front-line newspaper. “Her rifle never misses. Dozens of Nazis have been sent to Kingdom come by the fearless lady sniper.”

Unfortunately and unsurprisingly, some women combatants experienced sexual assaults by men within their own regiments, and had little to no opportunity for recourse. Sniper Polina Galanina testified before the Academy of Sciences Commission: “In fact, men do harass us. We had a section head, Dugman, who tried to get what he wanted by giving me orders…He summoned me to his barrack…I made my report and he began feeling me up. I pushed him off, he fell, got furious, and started all over again. I screamed, a patrol came and opened the door. They…gave him five days arrest.”

Almost 2,000 female snipers died in combat. Senior Sergeant Nina Onilova destroyed two enemy machine gun nests, and then sacrificed her life to cover the retreat of her comrades. Corporal Tatyana Barazmina was captured while defending wounded soldiers, tortured and killed. After running out of ammunition, Natalya Koshova and Mariya Polivanova waited until the enemy was close before detonating grenades in their hands.

As victory drew near, the women’s importance was radically diminished, as seen in this editorial in Pravda (Truth), published on International Women’s Day, March, 1945 (the same month as Lobovskaya secured the highway): “In the Red Army…women have very energetically proved themselves as pilots, snipers, submachine gunners [etc.]…But they don’t forget their primary duty to nation and state, that of motherhood.”

Two months later, on May 8, Berlin fell to the Soviets and, as citizens cried with joy and the skies were lit with triumphant gun salutes, Nina and the other 500 surviving female snipers wrote the names of their fallen comrades on the columns of the Brandenburg Gate.

But as the skies cleared and these young women returned to the Soviet Union, their expectations of being greeted as heroes, like their male comrades, were dashed. “How did the Motherland meet us? I can’t speak without sobbing…” said Klavdia S. to Alexievich, recounting her return to the Soviet Union. “It was forty years ago, but my cheeks still burn. The men said nothing, but the women…They shouted to us, ‘We know what you did there! You lured our men with your young c—-! Army whores…Military bitches…’ They insulted us in all possible ways…The Russian vocabulary is rich…”

On Victory in Europe Day, the female snipers’ identities and achievements, all the gains they’d made in terms of equality, were buried along with the names of those who’d died. One month later, President Kalinin told a group of demobilized female soldiers, “Do not talk about the services you rendered.”

In Girl with a Sniper Rifle: An Eastern Front Memoir, Yulia Zhukova writes: “I strove to forget everything to do with the war…I did not show my photographs from the war years to anyone. I burnt all the letters I had sent home…”

In these precarious times, we need to be inspired by women who risked everything to defeat fascism.

Remembering was dangerous in a country where hundreds of thousands of citizens had mysteriously vanished during Stalin’s 1930’s purges. Truth and equality disappeared with victory.

*

The long-term consequences of the forgotten, neglected, and expunged history of female snipers are evident in the erroneous conclusions drawn by historians like the UK’s John Keegan, who wrote the following in his 1994 book, A History of Warfare: “Warfare is the one human activity from which women, with the most insignificant exceptions, have always and everywhere stood apart…Women do not fight…and they never, in any military sense, fight men.”

Shortly after Keegan’s book was published, American women were accepted into combat roles in the Air Force and Navy—approximately fifty years after the female snipers’ debut in WWII, and fifty years after Lobovskaya’s all-female platoon defended the Polish highway.

Now, 80 years after VE Day, there is an alarming shift backwards to a Soviet-esque era. The recent US government’s order to remove military web pages that honor women—‘Women in Army History’ and ‘Navy Women of Courage and Intelligence’—is eerily parallel to the Soviet’s regime of silence and lies in WWII. If this suppression continues, if women’s rights continue to be eroded, their voices and their sacrifices will be stifled by the country they’ve defended.

In these precarious times, we need to be inspired by women who risked everything to defeat fascism. We need to fill the blank pages of history with the truth, to know what’s possible. We need to acknowledge and honor female sacrifices and triumphs, to speak out on VE Day against diminishing women in the military. Remembering should not be dangerous.

__________________________________

The Night Sparrow by Shelly Sanders will be available from Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers on July 1, 2025. Image courtesy of: Keystone-France via Getty Images.

Shelly Sanders

Shelly Sanders is the bestselling author of the adult novel Daughters of the Occupation and the acclaimed young adult historical novels The Rachel Trilogy. She began her writing career as a freelance journalist working for major publications, including the Toronto Star, National Post, Maclean’s, Canadian Living, Reader’s Digest, and Today’s Parent. She lives in Ontario.