Remembering Publisher Peter Mayer

Friends and colleagues share memories of former Penguin CEO and publisher of Overlook Press

Peter Mayer who died at age 82 on May 11 was a dear friend, a mentor and an inspiration—truly one of the greatest publishers of our time. He was the first—and maybe the last and only—publisher who worked with equal skill on both the global corporate level—as visionary leader of Penguin—and on the small independent publisher level—as dedicated steward of his beloved Overlook Press. What follows are some memories of Peter from his friends around the world that capture his charm, his brilliance and his ineffable spirit. Peter, we will miss you.

—Morgan Entrekin and George Gibson

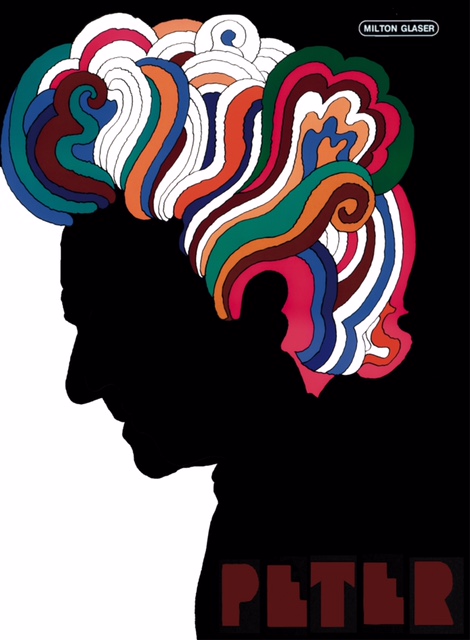

Peter Mayer in Ibiza

Peter Mayer in Ibiza

![]()

Very few people in our world change it, but Peter Mayer transformed publishing, not just in the UK but globally. He revived Penguin, a zombie company when he took it over, and made it the most formidable and admired publisher in the English language. He created vertical publishing in the UK, ending the sale of paperback rights. He was the first person to see the potential for local publishing in India and elsewhere, and, in setting up Penguin India, transformed the face of Indian publishing and literature, and he globalized Penguin turning it into an international force and the first of the big global groups. He taught, inspired, mentored and drove insane generations of people in publishing. And all that with peerless exuberance, energy, a passionate belief in books and literature, and most of all an indefatigable sense of fun.

—Andrew Franklin

![]()

When Peter moved to London to head up Penguin, he asked me if I knew of a weekend cottage he could rent. The only one, close to our Wiltshire weekend house, was in a farmyard surrounded by free wandering chickens, sheep, cows and pigs. Straight out of “Cold Comfort Farm.” Peter loved it (not sure Mary did) and that is where Liese was brought to within days of her birth. Ed Victor referred to the place as ‘the capital of shit’—and in many ways, it was. Driving back to the weekend house one Friday evening, Peter saw his farmer friend struggling with a cow in the middle of the pond near the house. He leapt out of the car and plunged into the pond, clad still in his suit, to help. For me, that story sums up Peter’s wonderful engagement with life.

Peter spent hours working at this table in the cottage.

Peter spent hours working at this table in the cottage.Photo courtesy of Deborah Owen

—Deborah Owen

![]()

Remember that spiral staircase in Peter’s flat? You had better have been dead sober when staggering down the triangular black steps—this is what I thought during my many overnight stays in Thompson Street. Peter, however, seemed more worried about getting up them again. When he came home from the office, he immediately made it downstairs to sit down at his massive wooden kitchen table – not to eat, of course (there was no space for a plate anyway among all the manuscripts, magazines, letters, files), but to continue work.

When I came back to Thompson Street after a dinner or some appointment at around midnight, Peter would still be at that table, fast asleep, head pillowed on his arms. As soon as he heard me come down those stairs (perhaps sometimes not altogether dead sober) Peter not only woke up – he was back to full alertness within seconds. After one or two hours of exciting and engaged discussion I would insist on helping him up that spiral to his bedroom to prevent him from spending his entire night asleep at that table…

Now he is flying up the endless and eternal stairway to heaven, no more assistance needed. I will miss him terribly.

—Niko Hansen

![]()

In the early 1960s, at the top of a skyscraper in New York City, I met Peter Mayer for the first time, in a tiny spartan office. He was then the editor at Avon Books, a paperback division of Simon & Schuster. He was the most handsome man in the new York publishing world, like a Hollywood star. He really was the most dashing and very, very sexy man. Passionate about literature, he spoke four languages fluently, and was totally informed about everything and everybody in international publishing, a global player. We became great friends forever.

He began a brilliant career: the CEO of Penguin Books in London, then the best paperback house in the world. Peter Mayer travelled tirelessly from one continent to another. He founded Penguin Australia and Penguin India.

I remember when he arrived in Naples one evening from New Dehli for the opening of our first bookshop there. He arrived late and did not have Italian money, not even the few cents required to operate the ancient elevator in the Grand Villa, whose owner threw a dinner for us and 200 guests. So late in the night we found him sleeping like a tramp next to the elevator.

I have met him at all the book fairs over the world from Jerusalem, New Orleans, Venice to Barcelona to Mexico, etc. He loved book fairs, especially Frankfurt where he stayed at the Hessischer Hof. He did book fairs to the max: from early business breakfasts to late nights, always with some beautiful girl around.

But I also remember him as the big boss of Penguin, wandering from booth to booth, with a shabby satchel on his shoulder, in search of rare books of poetry and prose.

He was always going to sleep during lunches and at breakfast, in a permanent state of jetlag.

He was famous for losing passports, telephones, computers and documents for conferences. I remember one hell of a time: Peter had been spending Christmas with us in the mountains in Austria, at the end of this world, and then he departed for London, leaving there with us in this most remote of places the text of a speech he was due to deliver in Berlin.

He loved birthday parties, which require never less than three days’ celebration. I remember his 60th in Amsterdam. There were around 30 of his best friends, and he organized for us in The Hague a private view of the fantastic Vermeer exhibition: all 35 Vermeers that exist in the world collected in one exhibition. And we were served a glass of ice cold Jenever, a sort of Dutch gin, at the entrance. It was magical: I happened to find myself alone in a room with five precious Vermeers and it was for me absolute paradise. And then his 70th in Tuscany, near Volterra in a big ramshackle Villa with all our friends eating, dancing and talking, for three days.

I remember being in Stockholm for Nadine Gordimer’s Nobel Prize when we danced (with all the Nobel Laureates dancing wildly in their hired frocks), and I lost the heel of my shoe that was decorated with fake diamonds. It flew off high into the air in this golden ballroom. “A Sputnik,” shouted an old bearded physics professor.

I remember meeting his father, the founder of Overlook Press at the Los Angeles book fair. He was sitting modestly in a corner on a little camping stool and offered me a drink. “My son Peter is a great man and a great publisher,” he said proudly.

And when I heard that Peter Mayer has given his daughter Liese a big wedding party in a bar in NYC inviting also the three most important women in his life I remembered these three words: Charisma, Charm, Chutzpah. These are the chief qualities of Peter Mayer, a complicated but wonderful human being.

—Inge Feltrinelli

![]()

Peter Mayer was admired and beloved in many places in the world – one of the first true global publishers. He must have had many favorite places himself, but I dare say that Amsterdam is among the places he loved most.

The love was mutual.

Was it because of the city and his many friends here that he also became fond of Dutch writers?

In any case, Peter’s contribution to the international appreciation of Dutch literature is immeasurable. The fame and recognition of the golden postwar generation of Harry Mulisch, Willem Frederik Hermans, Gerard Reve, Cees Nooteboom, Hugo Claus, and of such classic masters as Multatuli, Slauerhoff and Louis Couperus, are unthinkable without Peter’s passion and support.

Years ago, on a sunny afternoon, I went with Peter to look at a house along one of the canals he considered buying. It never happened. It doesn’t matter. In a way, Peter will forever be a citizen of Amsterdam.

—Robbert Ammerlaan

![]()

Peter was not just one of the greatest publishers of the last 50 or more years, he was genuinely an international one, as at home in the UK, Holland & German speaking countries & other parts of the globe as he was in the US.

He had as great a talent too for friendship & he so enriched all our lives who were lucky enough to be his friends, and we were very many, everywhere books are published and read.

With his great friends Peter Carson, as editorial director, and Betty Hartell , his long serving secretary at his side, Penguin was a quite extraordinary power house.

Without Betty, of course, some travel admin could go awry. After a week’s travel together in Russia in the 1990’s, Peter & I were having a last dinner in Moscow in the rather austere monastery he insisted on staying in, when he said, Do you see this little key here? It’s the key to the safe of the hotel in St Petersburg we were staying in, where I’ve left my passport & air ticket & the hotel manager says annoyingly it’s the only one, with no duplicate. Could you possibly find someone to take the night train tonight & fly back tomorrow with all my stuff? I felt then for Betty! This of course duly happened, a Russian friend found a student who Peter completely charmed & Peter was able to fly to Kiev the next day to give a doubtless brilliant talk & on to NYC.

—David Campbell

![]()

When it comes to bestriding the narrow world like a Colossus, Peter set the bar for publishers at an Olympian height. He was already a legend when I drifted into the business in 1977, but what legends do is to build on achievements and expand their hopes and reach, and once he departed Pocket Books for Penguin his growing empire soon included America, Britain, and then India, with a private army of friends throughout the trade in every publishing capital and outpost and at endless conferences and book fairs.

At Frankfurt every Tuesday evening was marked by “the Peter Mayer dinner,” and I eventually was blessed with an invitation and the opportunity to make many friends myself among his great supply of them; and this event continued, in his honor, even after he’d retired from that particular maelstrom. He was no stranger to any turbulence whatsoever, though, as demonstrated by his stalwart support of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses. Nor was his contrarian conviction late-developing, as witnessed by his championing of Henry Roth’s Call It Sleep at Avon Books in 1964, thirty years after its initial publication and global obscurity, then suddenly a bestseller. There is as well his ongoing devotion to the works of Charles Portis and countless other writers at the Overlook Press, which he founded with his father in 1971 and continues that eclectic mission to this day.

The engine driving his stupendous accomplishments was simple: a love of books and literature and the people who create it, ranging across all genres with characteristic passion. And his love of life enriched it tremendously for anyone lucky enough to spend time in his incomparable company.

—Gary Fisketjon

![]()

I arrived at Publishing News in January 1984, a newbie in the trade. Penguin had by then been turned around. In those days CEOs took phone calls and answered questions themselves, not via obstructive corporate comms. Peter was always helpful and straightforward and kind. We got to know each other over the years: conversations at parties, tea at The Muffin Man, which was local to Penguin’s Wright’s Lane offices and where—during periods of giving up smoking and well before the ban came in—he would cadge cigarettes off other patrons.

There were lots of grand parties in those days but the one I remember was the intimate party at (I think) the old Whitbread Brewery in Chiswell Street, where Allen Ginsberg was feted for a large volume of his collected poems. Allen warbled to his autoharp, as often he did. And Peter told me a great anecdote about driving him from New York to San Francisco after he’d picked up Allen and his partner (was it then Peter Orlovsky?) one New Year’s Eve as a cab-driving grad student.

I interviewed him at length once, in late 1998/1999 during one of my many Stateside trips, when he was back in New York and running Overlook Press full time, relishing the hands-on of it all and loving Greenwich Village, where he lived and worked. I was struck by his always talking in long, often complicated, sentences without ever losing the thread or mussing up the syntax. Few people can do that. Peter was a wonderful and wonderfully brilliant man. Publishing, and the world, has lost a genius and a visionary.

—Liz Thomson

![]()

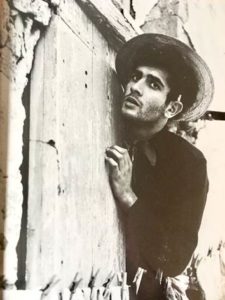

Peter Mayer and Antje Landshoff-Ellerman

Peter Mayer and Antje Landshoff-Ellerman

![]()

Perhaps it was because we shared a common Ashkenazim background or perhaps because we both smoked, both dressed less than smartly, both had quite early grey hair that we quickly became friends. Actually friends is not quite the right word. I thought of him more as an elder brother and he, I imagine, just thought of me as a youngster ready to be taught the real rules of publishing. Money matters but not at any cost. Early in our friendship I was trying to exact an inordinate amount of money from Penguin to renew their paperback licences for many of Graham Greene’s best books. His executive team rejected my demand and so we were prepared to issue our own paperbacks. At the last minute, a message came through. Peter realized that Penguin without Greene was simply not right and the cheque was in the post.

Peter had many strengths. The ability to drive and stay awake simultaneously was not one of them. He and a very young Liese (five years old?) came to dinner with me in Oxford in order to meet an old friend of his from his student days at Christ Church. I was then working in London and had a small flat there and Peter offered me a lift after what had become a very boozy dinner. With Liese in the back seat, we set off in his car. By the end of the road he had clipped three wing mirrors. By the time we reached London I had been forced to prod him on occasion as his eyelids drooped and we swerved across the road. I feared for Liese as well as we two in the front seats. We arrived safely. Once more Peter had beaten the odds.

As he also beat the odds in publishing. A few years later I was working at Macmillan. By virtue of an arrangement with the Daily Telegraph we held the rights to a series of books containing a strange new puzzle called Sudoku. Our sister company in USA, St Martin’s Press, were not interested, nor was anyone else. On a visit to our offices the rights director showed him the proofs. He snapped up North American rights and published in weeks. Sales were huge for Overlook, as were royalties to Macmillan. To their credit, St Martin’s quickly realised their oversight and commissioned their own successful Sudoku series, so the two Macmillan entities one way or another cleaned up on that phenomenon thanks to Peter.”

—Richard Charkin

![]()

Peter was a strong human being. I never saw him weaken, and I saw him afraid only once in almost thirty years. It wasn’t when we were caught unawares by a storm while on his lobster boat in the Atlantic; or when the Chechnyan consigliere confiscated our passports in Baku because he wanted to play with us a while longer. It was in that same city, though, when Peter walked into a sanitorium to have one of his front molars reconstructed after breaking it while eating the ubiquitous sunflower seeds that old women sold out of five-gallon plastic buckets on the street. (When Peter wasn’t smoking he was nearly always foraging.) He thought he could ride out the pain until we returned to New York, but on the way to a town deep in the Caucasus Mountains called Quba, the driver kept having to stop because Peter screamed each time we hit a bump on what took itself for a road: lots of stops, lots of shouting. I was more worried about the glass jars of caviar in the trunk.

Those same white buckets flanked the benches in the hallways of that sanitorium back in Baku; instead of sunflower seeds, mucus and blood. It reminded me of a certain veterinarian clinic in Nebraska. As we sat there on one of those benches, Peter’s right leg began moving up and down more rapidly than normal. “Robert,” he said, “have I ever told you about dentists and Peter Mayer…?” Finally, he was summoned. This “dentist” was twenty-two and still in school. But he was cool. Peter liked that he was playing country music. He sat Peter down, no small talk, and began pumping his foot to get the drill going. Peter shouted, “You forgot the novocaine!” The young man said, “Nyet,” no novocaine,” and leaned in….

I sat outside wincing the entire time; I heard sounds behind that door that might still be with me. Lots of stops, lots of shouting. Finally, I was summoned. Peter wanted me to choose the color of enamel that most matched his tobacco-stained teeth. Having to choose the color of a book jacket is one thing but this choice could reflect badly on me for the rest of my life, or at least the rest of Peter’s life. Thank God he didn’t pay much attention to his smile, I thought, and chose the color that most favored that smile, one that had also launched not an insignificant number of ships.

—Robert Dreesen

![]()

Poignantly, one of my earliest memories of Peter is a conversation we had about death in the early 1980s. He was in his mid-40s. We were walking round the Brompton Cemetery in west London one Sunday morning as he outlined his plans to start up the Viking imprint in the UK (he was quick to realize paperback imprints like Penguin were going to need their own sources of supply) when I made a glib remark about the dead lying all around us. ‘I don’t want to die yet,’ he said unexpectedly. ‘There are so many things I still want to do.’

And, boy, didn’t he just! For about a decade, between his arrival at Penguin and the publication of Satanic Verses, he sprinkled stardust on British publishing. It helped that he seemed so exotic to us—he was impossibly handsome, impossibly enthusiastic, and he didn’t drink—all rare attributes in London. He managed to make the fusty old business of publishing seem glamorous, not just to the people working in the industry but to millions of readers too.

It was the combination of street trader and intellectual which made him so charismatic. He once scooped me up and we set off together with a case of samples to try to persuade a department store to sell some books; but I’ve also seen him host a dinner for the heads of European houses at Frankfurt, completely fluent in German and Spanish. The Satanic Verses affair undoubtedly knocked something out of him—he was acutely conscious of the responsibility he bore for Penguin staff around the world. It was a heavy burden and I think it came close to grinding him down. But I prefer to remember the Peter who gleefully recalled driving Allen Ginsberg and some Beat cohorts out west in a cab; who told the story of having to shake hands with the egregious Albert Speer; who confided to me with a twinkle in his eye that he’d once shared a girlfriend with Ray Davies; whose eyes lit up with pleasure when you mentioned the novels of Joseph Roth; who suggested, presumably tongue in cheek, that he and I buy Bob Dylan’s old family house in Hibbing.

It was quite some life, and I can’t really believe he’s gone—he seemed, like Dylan, indestructible.

—Tony Lacey

![]()

Losing Peter is losing a giant. We’ll miss his manic energy, his absolute passion for books, his delight in pushing boundaries, and his dedication to the old-fashioned craft of book publishing. Who else could have taken overheard conversations on the streets of London to his extraordinary success in leading the market for Sudoku? It is my shame that we never got to play that tennis match in Woodstock: perhaps a good thing, though, as he probably would have won. Go well, my friend.

—Scott McIntyre

![]()

Early on when he was the publisher of Avon and then of Pocket Books (he was my boss ), when buying rights to publish from the hardcover houses was called reprinting, when original paperbacks were considered second class books with little or no value, Peter was adamant about changing the game. I was there when an editor complained he was having a hard time lowering his standards to buy paperbacks. Peter went quiet, put out his cigarette, lit another one, and said severely: “You don’t lower your standards to publish paperbacks, you expand your horizons.” Peter was Brilliant, Kind, Loyal, Exasperating, a Great Publisher, an Adventurer, Generous Adviser, Enthusiastic Mentor, my Boss and always my Friend who liked to eat caviar as well as radishes with butter and salt.

—Carole Baron

![]()

I met Peter in 1977 and as it turned out I worked for him for twenty years. After he left Penguin we were great friends for another two decades. I loved his intensity, his taste for both high and low culture, though his enthusiasm one Frankfurt for A History of Dentistry seemed a little misplaced! His appetite for risk and excitement was contagious. Being around him was sometimes intoxicating. And there was a great sense of humor, and a sense of irony that is rarely seen in the corporate world. He was a wonderful supporter of editors. I remember him hurtling down the corridor towards my office waving the New York Times Book Review when J. M. Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians was hailed as a masterpiece by Irving Howe. There were calls from London in the middle of the night to discuss a book cover he had just plucked from the transatlantic pouch. There was partying at the Chez Swan discotheque in Proust’s old hangout in Cabourg to celebrate Penguin’s 50th anniversary. There were the stresses of the Rushdie affair and the cat that went missing during the party at Peter’s flat for the brilliant Robert Fagles and his translation of The Odyssey. And so many wonderful conversations about our Jewish fathers, our daughters, our industry. It’s hard to believe he is no longer here.

—Kathryn Court

![]()

Peter was the youngest of us, and since he left Viking/Penguin he was getting younger every year. He spoke a very elaborate rich German, and after the death of Carol Janeway he was the last German speaking publisher in New York. I knew him for exactly fifty years.

I remember very well picking him up at Viking (first to go home, then for drinks in a bar, and afterwards for dinner, totally private, no schmus, Italian, former Mafia); schlepping (like Roger W. Straus would have said) jute-bags with hundreds of contracts from ten different publishing-houses in eight different countries to his apartment, where he said, let us just look at the news before dinner, and got us some drinks from the fridge, and when I came into the bedroom, he was sleeping like a lion, this beautiful man, who just came from India and had to go next day to London, but wanted to have drinks and dinner with me in between. So he was snoring, and I saw the news, and when I left his apartment, he looked at me in surprise and said, see you in London and look into the books I brought for you; and from London he called, and said, when I woke up to go out with you for drinks and dinner, you were already gone and had left me with all those contracts, but next time we go…..

His passion, his friendliness, his very good memory, his good (and his bad )manners, his personality, his knowledge, his judgement, his misjudgement, but most of all: his ability to listen to friends. Unforgettable!

—Michael Krüger

![]()

Peter Mayer was a giant in a generation of great publishers. Unfeasibly handsome, he also had such a powerful personality that it was impossible for him not to dominate a room, let alone a company, however large that company became. His impact on the lives of those of us who worked for him was instant and remains indelible.

Peter was not a man for the detail. But he was a visionary. It was he who took Penguin, at the time a desiccated English paperback house, and built it back up into a global brand. No respecter of hierarchies, including literary ones, he would on the one hand insist that we publish European masters in translation, but also that we give equal emphasis to The F Plan Diet or mass market novel The Far Pavillions, having an equal eye for high culture and high sales, and thus building a company that was profitable but also resilient.

A paperback publisher to his boots, Peter then began to tear down walls. Having first set up Viking as a UK hardcover company to sit alongside the American company already owned by Penguin, in the mid 1980s he acquired The Thomson Group of publishers, including Michael Joseph and Hamish Hamilton (and also me!), thus securing direct access, or ‘Vertical Publishing’ as it was then called: the acquisition of hardcover and paperback rights in one go. As an inveterate traveller all his life, he also turned his gaze outwards, building or creating Penguin companies in Canada, Australia, South Africa and India: companies that were not just distributors, but would also originate books that could be sold locally and internationally. He was also the first publisher to really think about branding, not least of Penguin itself, but also especially in Children’s publishing, bolstering Puffin with properties like Frederick Warne, with all the Peter Rabbit books and merchandise, and with Ladybird.

In the late 80s Peter’s gaze was drawn back to America, building Viking Penguin there by acquiring Putnam, Dutton and NAL. New York became his centre of operations, but famously in that time he was constantly flying around the globe, wreaking such damage on his body clock that he would often fall asleep mid-sentence, only to awake moments later, so that meetings became a nightmare as we all tried to navigate the intermittent silences when he had nodded off.

His appetite for life was prodigious, as was his appetite for food. At one Sales Conference I remember him helping himself to two plates from the buffet, and sitting with one on the table and one on his lap. When I pointed out he could always have had a second helping instead, he replied that someone else might have finished the dishes he wanted by then. My own appetite was somewhat curbed when he stubbed out his ever-resent cigarette in an egg. But his appetite and lust for life was very much more than metaphor!

The decision of whether to publish the paperback of The Satanic Verses, or whether to listen to other advice about the safety of the people who worked for him was a distressing challenge that faced Peter and the directors of Penguin and took us into an area that at the time was a unique challenge. It was perhaps the first rumblings of a changing world order, and it’s sad that this episode might be the event for which Peter is most remembered. In truth, the book was always available, if not in paperback, and it’s a special irony as, of all publishers in that period, Peter was one of the most inclusive and global in vision. I would say that he was open to all literatures, all cultures, all religions. In fact he was interested in diversity long before that became anyone’s corporate mantra.

Those of us who worked closely with him remember being challenged, being driven to distraction, being infuriated, fighting, laughing, having a great time. We remember clouds of noxious cigarette smoke. We remember being inspired as he drove the company at that time towards becoming a great global brand. We also remember how we never wanted to get into a car if he was actually driving, because he had a bad habit of falling asleep at the wheel and coming off the road.

Most of all, we remember him with love.

—Clare Alexander