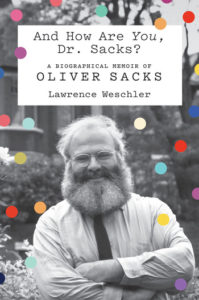

The Road to Oliver Sacks'

Lawrence Weschler on Meeting a Then-Unknown 48-Year-Old Neurologist

It would still be a few years, though, before I actually got around to reading Awakenings. Indeed, it was rereading Husserl alongside Irwin that put me back in mind of Natanson’s glowering assignment. But the impact of reading the book when I finally did indeed proved utterly galvanizing, and I couldn’t stop thinking about it.

With the benefit of magisterial hindsight, I think one can safely say that Awakenings would prove Sacks’s defining masterpiece, his Moby Dick, a perfect fusion of form and voice and tone and thought and witness, the source from which everything else would subsequently flow.

Most readers by now know the story (at any rate, I suspect, most readers of this book do, if for no other reason than because of the eventual movie, starring Robert de Niro and Robin Williams, but remember, that was still a good decade off, and at this stage both the book and its author, as I say, were still pretty much unknown). But just to level the playing field, recall that following the First World War, there sprung up a horrendous influenza outbreak that ended up killing millions and millions of people all over the world, more indeed than the war itself. Of those who survived that onslaught, a few years later, some though by no means all, and it was difficult to tell who or why—often younger survivors though, people in their late teens and early twenties, in the midst of the full vibrancy of their youths—simply…began… coming…to…a… ….halt.

Often from one day to the next, they subsided into stupefying trances: deep, petrified sleeplike removes. Thousands of them, hundreds of thousands, and again all over the world. The terrifying phenomenon was as widely discussed and decried at the time as AIDs would be decades later, though after it disappeared, almost as suddenly and unaccountably as it had arrived, in the late 1920s, its memory was to be widely suppressed and presently almost completely forgotten. Of its many farflung victims, some simply died, many recovered completely, but others persisted in their eerie frozen states, at first cared for by overwhelmed families, but presently given over to institutional Homes for the Incurable, which rose up all over the world during this period in the late 20s and into the 30s.

There, more of them died, some recovered, others persisted, blending into wider communities of variously outcast souls (catatonics, the demented, schizophrenics, severe autistics, and so forth) as the Homes became repositories for all manner, as it were, of (as his life-friend Bob Rodman puts it) the Refused. Years passed, decades. Most died, a few still lingered on.

In 1966, a 33 year old washed-up would-be medical researcher turned clinician, from out of London, named Oliver Sacks arrived at Mount Carmel, as he would subsequently call the specific institution in an outer New York borough that would become the site of the ensuing drama. (Back in Van Nuys, I would have just been entering Birmingham High.) Gradually he began to notice there was something different about a specific group of the place’s scattered residents, these “living statues,” as he took to thinking of them, and he became convinced that deep inside, utterly removed, they might still be very much alive. He tunneled deep into the place’s back records, developing their case histories, which indeed showed remarkable congruencies: they were all suffering from versions of a deep “post-encephalitic Parkinsonian syndrome.” Eventually he separated out about 80 of those patients from the wider Mt Carmel population of some 500, gathered them into a ward of their own, where he could engage with them more thoroughly, and as individuals. Months passed.

Around this same time, reports began swirling about the development of a new miracle drug, L-dopa (or levo-dopa, technically L-3, 4-dihydroxyphenylalanine, a concentrated synthetic version of a naturally occurring neurotransmitter precursor) that was said to be having remarkable results with ordinary Parkinsonian patients. Despite misgivings about informed consent and a distinct suspicion at the whole messianic fervor surrounding the drug, Sacks presently resolved to try a few of his patients on the compound, and the effects were so instantaneous and remarkable that he was soon prescribing it to most of the people on the ward.

This would have been the early summer of 1969, a period that he would later characterize as The Great Awakening, a season of almost Mozartian vitality and grace: suddenly, after a decades long stupor, people simply came alive, limber and vivid, the ward pumping with vitality and good cheer. But as the weeks wore on, first one and then another of the patients, and presently all of them, began experiencing side effects of harrowing proportions (oculogyric crises, spasms and seizures of all sorts), terrible spin-outs that could not be modulated through titration, no matter how exacting, and the ward gave way into a sort of bedlam: these months of late summer and into the fall being the time of Tribulation, as Sacks would subsequently characterize them. With the passing months, into 1970 and beyond, most of the patients would subside into a final phase of Accomodation, never again to be as vivid as they had been those few weeks of Awakening, nor perhaps as removed as they had been before that, nor as wracked though as they had been during Tribulation, bathed rather in a becalmed sort of acceptance, a dark and narrowed sort of grace.

Sacks was wracked by feelings of wastage and uselessness. Indeed, he was at times floridly neurotic, on all manner of themes, swinging wildly between feelings of grandiosity and failure.

These three—Awakening, Tribulation and Accomodation—at any rate became the conceptual categories within which Sacks would frame his account of the drama a few years later, but the core of his book would be 20 highly individuated and achingly evoked case histories: a new kind of medical writing, or perhaps, the revival of an old one. At any rate, perhaps both behind and a bit ahead of its time, as the book languished for many years, unrecognized.

But as I say, and belated thanks to Mr. Natanson, I eventually read it myself and was quite overwhelmed, albeit a bit puzzled. Because—it took a while to narrow in on my sense of suspension—for all the drama and fellow-feeling evoked by the text, the figure of the doctor himself was remarkably fugitive, held back, subdued. What, I wondered, must it have been like for him? The more I continued to ponder the question and (Toddlike) to hone and focus it, the more I came to sense that the true deep drama of the story, at least in his regard, had less to do with the decision to administer the drug and all that followed from that, but rather with the mystery—what could it have been about him and his professional formation and his own past?—behind the fact that he and he alone had proved to have the—what?—the perspicacity to notice those particular living statues as somehow distinct from the others, and then the moral audacity to imagine that there might in fact be ongoing life buried deep within those long-extinguished cores?

Being a good little instance of my own specific type in that specific time and place (a free-floating would-be intellectual in the Los Angeles of the late 1970s), I responded to those questions in the way we all seemed to be doing in those days: by writing a preliminary screenplay treatment. And it was this that I first mailed to Dr. Sacks in the fall of 1980 (around the time I’d completed my Irwin project and was beginning to shop it around), asking if anyone else had approached him about the idea of turning his book into a film, were the rights still available, and, if not, and if upon reading the treatment he found it worthy, would he be willing to let me pursue the matter?

There followed several months of silence, but then, early in 1981, in fact on February 13th, my 29th birthday (when he would have been, let’s see, 47), I finally received an envelope containing a letter he’d written some months earlier but somehow misaddressed which then got returned and then mislaid but eventually, according to the cover note, recovered and was now being sent off once again. “I am most grateful for the kind things you say,” the letter began, and happy that AWAKENINGS apparently found some deep resonances in you. One always has the fear that one lives/works/writes in a vacuum, and letters like yours are very precious as evidence to the contrary. Indeed, I never regard the writing of anything as ‘completing’ it—the circle of completion must be made by the reader, in the individual responses of his heart and mind—then and only then is the circle of the Graces—of Giving, Receiving, and Returning—complete.”

The letter graciously went on to explain how there had been occasional interest in a film version of his book, though nothing definitive and nothing specific at the moment, so he was not adverse, but that we should at some point in the months ahead try to get together to discuss things further. Which was fine by me: I was still mainly busy trying to place that Irwin manuscript (we were a few months out yet from Mr. Shawn’s phone call) and meanwhile pursuing reporting on that ill-fated Playboy piece.

Sacks and I continued to correspond sporadically through this period (letters which I have alas misplaced—or rather correspondence that doubtless lies in a folder moldering in some Southern California attic, left behind in my sudden upcoming move), but I remember one letter in particular in which I suggested that I understood why he’d given the institutional home in question the clever pseudonym of Mount Carmel (St. John of the Cross, Dark Night of the Soul and so forth), but that it seemed to me that his text was much more Kabbalistic (shades of Natanson, again), which is to say Jewish rather than Christian mystical—was I wrong?

To which he replied with the first of his mammoth multipage handwritten responses. For indeed, as he went on to explain, the actual place was named Beth Abraham, in the Bronx, his family was deeply Jewish in all directions, in fact his first cousin was Abba Eban, the Balfour Declaration had first been broached and then largely composed in various London family basements, and perhaps most importantly, the great inspiration of his medical life was the Soviet neuropsychologist A.R. Luria, who, who knows, may perhaps have been a descendent of the great 16th-century Palestinian Jewish mystic Isaac Luria, one of the principal students and explicators of that ur-Kabbalistic text, the Zohar.

After that exchange, our contacts became more and more cordial (even though the initial pretext of a possible screenplay gradually seemed to fall away as I became more and more consumed with my dawning New Yorker responsibilities), until, indeed, that day in June of 1981 when I rented a car and drove out to meet him in person, for the first time, in his own relatively new home on City Island.

*

That, as I say, was the first entry in my notebooks. There would be many more—presently 15 volumes worth across four years when, pretty much on the model of my three previous years with Irwin, he and I would get together several times a month, if not a week (if anything it was more me in this instance, traveling on increasing assignments from the New Yorker, who’d be the one to skip town and upend the rhythm of our meetings). Fairly early on I resolved to feature him as a subject for a future profile (Shawn immediately approved), a profile that grew into a prospective book as the months passed.

Oliver Sacks and Lawrence Weschler at a public conversation sponsored by the Lannan Foundation in Santa Fe. Photo credit: Don Usner

Oliver Sacks and Lawrence Weschler at a public conversation sponsored by the Lannan Foundation in Santa Fe. Photo credit: Don Usner

Oliver was agreeable, if a touch wary. I would travel with him to London, join him on rounds (encountering among others the last remaining living Awakenings patients), dive with him into Natural History Museums and Botanical Gardens on both continents, join him for meals in New York City, or head out again and again to City Island, where he’d give me free run of his own files. I would start recording interviews with colleagues and friends from his youth, and others.

It was an odd period in his life. As I say, he’d already written what would in time (though not yet) come to be seen as his masterpiece. In the meantime though he’d fallen into an excruciating siege of writer’s block on the book immediately following that, an account of a leg accident of his own and its philosophically and therapeutically fraught aftermath. That terrible blockage (which actually often took the form of graphomania, as he spewed forth millions upon millions of words, just not the right words) would eventually take up eight years of his life (our own first four being the final four of that siege). Sometimes, a few days after one of our dinners, I might receive a bulging envelope, featuring a dozen-paged, hand-typed (two-finger pecked), single-spaced amplification on some of the things we’d been discussing.

He was wracked by feelings of wastage and uselessness. Indeed, he was at times floridly neurotic, on all manner of themes, swinging wildly between feelings of grandiosity and failure. He was pretty much of a recluse out there on City Island, still as I say largely unknown, church-mouse poor, entertaining relatively few visitors (and still fewer friends), finding what surcease he could (often, in fairness, quite considerable) in his daily outings to see his patients. He and I kept up our conversations: he seemed to enjoy, by and large, dredging through his past and showing off his wards.

Four further years on, his blockage would finally lift and he’d at last complete that damned leg book of his—with a whole flood of long dammed up material clearly just waiting to burst forth in its wake (for indeed, a year later he would release his breakthrough collection, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, with almost a dozen others now to follow in regular succession, celebrated bestsellers all over the world, and by the end of the decade Awakenings indeed would see its translation to the screen, nothing to do with my treatment alas, with yet more fame and celebration to follow that, he’d systematically put his life in order or rather find an invaluable assistant who could, and his days as a recluse would fall away)—anyway, just before all of that, I decided to take a retreat of my own, put my notes and transcripts in order (the index to my notes ended up taking over 250 pages) and finally embark on the writing of my long gestating profile.

Someday someone is going to take on the project of a full length Oliver Sacks biography, and it’s going to be an extraordinary book when it happens.

At which point, Oliver asked me not to.

He wouldn’t, he assured me, care what I did with all the material after he was dead, but he couldn’t live with the prospect of encountering it while still alive. He was wracked with compunctions about one particular aspect of his life, which—well, that’s the story, or an important part of it, anyway, isn’t it? You’ll see. (Some of you may have guessed, and others may have been peeking.)

Instead, he hoped that we could remain friends, and indeed we did. I married and he welcomed my bride into his life (and she, somewhat more forebearingly at times, him into ours). She and I had a daughter who became his goddaughter, and she grew to adore him (of which more, as well, anon). We continued to have splendid adventures together. And then on the far side, just recently, as he indeed was dying, he not only authorized me to return to that long-suspended project. He positively ordered me to: “Now,” he said, “Do it! You have to.”

*

It would necessarily be a different project. Back then I was imagining something of a mid-career biography, and taking notes toward that. But life intervened, other things started consuming my attention, decades passed, and I stopped chronicling things Sacksian in the way I would have had to if I were now going to be launching into a full scale biography. In any case, have I mentioned? the man was a graphomaniac. Talk about shelves groaning under the weight of notebooks! Someday someone is going to take on the project of a full length Oliver Sacks biography, and it’s going to be an extraordinary book when it happens, but that person is going to have to be a lot younger than I am now. I wish him or her well: and I envy them.

Instead what I propose to offer is in its core something more like a memoir of those four years when I was serving as a sort of Boswell to his Johnson, a beanpole Sancho to his capacious Quixote.

The prospect was considerably complicated just recently, quite late in Oliver’s life and indeed just before he issued his command that I now return myself to the fray, by his publication of his own autobiography (into which those of you who have been peeking will have done so). At first I even surmised that that book might have rendered any offering of my own superfluous. But with time I’ve come to feel decidedly otherwise. For one thing—and how can one not celebrate this?—Oliver’s late-life telling of his own tale was suffused with a hard-won grace and serenity. The Oliver one encounters in my notebooks from that time over 40 years ago was a decidedly other creature, far more wildly (and sometimes, dare I say, delightfully) various, his accounts (the ones at any rate that were later to recur) pitched to a decidedly different register.

Nevertheless, I’ve struggled some on how to structure the account of those years: conversations with him and with others about any given phase of his life, for instance, were scattered throughout my notebooks’s pages—one little detail here, another 30 pages on, still more, 100 after that—and part of me wanted to gather all the material about, say, his childhood, in one place, followed by all the material about his teen years, and so forth. But the thing is, that book now already existed, at least in one form, his very own, and it seemed a bit early to be repeating the same exercise. On second, and third and fourth thought (indeed, a Leg-like blockage of my own began to loom up, portentously), I finally came to feel that I ought largely honor the chronology of those four years, giving the reader a lived sense of how all those details gradually came together for me, offering that reader (and perhaps that future full-scale biographer) a chance to make evolving sense of it all for themselves.

______________________________________

This is the original version of the condensed chapter which opens And How Are You, Dr. Sacks?: A Biographical Memoir of Oliver Sacks by Lawrence Weschler. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux August 13th 2019. Copyright © 2019 by Lawrence Weschler. All rights reserved.

Lawrence Weschler

Lawrence Weschler, a longtime veteran of The New Yorker and a regular contributor to The New York Times Magazine, Vanity Fair, McSweeney's, and NPR, is the director emeritus of the New York Institute for the Humanities at New York University and the author of nearly 20 books, including Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, a life of the artist Robert Irwin; Mr. Wilson's Cabinet of Wonder, about the Museum of Jurassic Technology; Everything That Rises: A Book of Convergences; A Miracle, a Universe: Settling Accounts with Torturers; and Vermeer in Bosnia. His newest book, And How Are You, Dr. Sacks?, a biographical memoir of Oliver Sacks, was published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux on August 13, 2019.