Remembering Mark Strand: Lover of Voicemails, Roaster of Chickens, Writer of Poems

Rebecca Dinerstein on the Life and Times of a Wonderful Mentor

Poetry Month is also the birth month of Mark Strand, the beloved poet, translator, and professor, about whom much has been written. A famously handsome poet laureate and recipient of the Pulitzer Prize, his 80 years were amply and adoringly chronicled upon his passing in 2014. In the years since, I have mourned my own memory and lack of him.

I met Mark when he came to give a reading at my college. Afterwards, he invited: “Feel free to write to me whenever the spirit moves you.” The spirit moved me pretty often (wouldn’t it move you?), and in New York, after graduation, Mark became my sort of mythic playdate grandfather. We did something small, together––a sandwich, a bookstore––once or twice a week, for the last four years of his life.

Mark had settled into a Chelsea apartment after decades of life traveling. During childhood alone he’d lived in Halifax, Montreal, Philadelphia, Mexico, and Peru. He’d taken on a similarly various education: after studying at Ohio’s Antioch in the 1950s, he enrolled in Josef Albers’s painting program at the Yale School of Art and Architecture, turned from there to Florence to study 19th-century Italian poetry on a Fulbright Scholarship, back to the Midwest for the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and south to Brazil as a Fulbright Lecturer in 1965.

He taught around the northeast in the 1970s, and then spent the 80s in Utah. There lived a cowboy at his core, both contrived and utterly essential to his personality. I gawk sometimes at what a classically American figure this Jewish Canadian giant must have cut as he strode across Florence in 1960, tall and quiet and twinkling.

The distinctiveness of his work informed many successive generations of students. In college, a professor asked my classmate to “stop reading only Mark Strand.” That was a common practice: take Strand as a singular oracle and hope to mimic his swagger. Mark’s poetry is known for its dry and surrealistic cynicism, a dark attitude punctuated by winks. I take this style as a function of Mark’s in fact totally joyful striving for the sublime.

His pursuit produced two branches of activity: foremost, a poetry that found transcendence frustratingly opaque and untouchable; running parallel, a collecting of earthly pleasures in which he could most immediately detect some banal trace of perfection. He needed daily life to open minor pathways toward major harmonies.

Mark liked it when good got called good, no matter whose or what kind: good socks, good syntax, good Syrah.

He loved roasted chicken. But he loved more to demonstrate chicken-roasting. “Come here,” he would say through a signature clenched jaw. “I’m gonna show you how to roast a chicken.” I can’t remember his technique because I was so distracted by his pleasure. He loved sausages when he burned them. He loved Rome as a shoe source and he really loved Roman shoes. He became excessively fond of a metallic Uniqlo jacket in which he christened himself “the silver bullet.” I remember him most often like this: matching the poles of an E train, riding out of Midtown, deliriously pleased.

He loved his daughter and grandson so much he learned from them, and took them as his leading examples: Jessica’s elegance, magnetism, and strength; Lucian’s young scholarly talent for Latin and indeed his ancient, almost heroic beauty. Mark championed emerging poets and independent bookstores, especially 192 Books, a narrow and exquisite shopfront on Tenth Avenue near his apartment.

He’d stealth-curate the window himself, planting copies of limited run chapbooks he admired or the best of his students’ publications. For all his pomp and delectable vanity, he lacked selfishness: he wanted the work of others to find a sure place, to garner recognition. He liked it when good got called good, no matter whose or what kind: good socks, good syntax, good Syrah.

He loved voicemails. He loved to leave a long, melodious voicemail. Voicemails about towns called Walla Walla, about afternoons in Chicago and Madrid. One very urgent: “Becky it’s the Cobble Hill blend. Cobble Hill blend.” He didn’t use many machines. I’d regularly find a stranger standing in the dark back of his apartment, fixing his computer. He found the computer’s dysfunction boring and inevitable. There seemed to be so many people volunteering to fix Mark’s computer all the time. He liked the volunteers. He liked a telephone.

Perhaps all accounts of male heroes will now need to include the following––in any case, I’m compelled to address an aspect of his record that wouldn’t have come up as recently as 2014. Mark enjoyed a big-winged, far-flung love life, his whole life through. Somebody is bound to tell you about his many liaisons with women across different ages, sensibilities, geographies, and levels of seriousness. Mark was six-foot-seven and charming. But most significant: seduction was never a prerequisite for his professional attention, artistic feedback, or personal care.

Mark entered into a cycle of effort, doubt, and revision at once common to all artists and specifically informed by his cultivated self-knowledge.

Of all the male mentors I’ve known, Mark was (by far) the most unconditionally supportive, and the most welcoming of other men in my life. He was basically too fabulous for false competition or power play. He’d eat dinner with just my boyfriend when I traveled out of town, and generously and insightfully critiqued the work of young writers I dated. Lord knows my boyfriends (I had several during the years I knew Mark) lapped up the majority of his chicken-roasting lessons––I’m vegetarian. Mark is, to me, the great example of how to be exuberantly sexual and genuinely dignified. May his memory be an education.

After the 2012 release of his final individual poetry volume, Almost Invisible, Mark concentrated on his collages. His pursuit of visual art, following his substantial early training, had ebbed and flowed, but never left him. Weather and work combined for him in the form’s colors. “I have made a few more collages. The days are leisurely and long, the sun never fails to show itself.”

Or, “Spring was here today with lots of sun. Tomorrow rain again… Made some more collages. Am getting better I think.” He entered into a cycle of effort, doubt, and revision at once common to all artists and specifically informed by his cultivated self-knowledge. “I made some bad collages, but managed to interview myself, and the self was satisfied. How are you doing? Love, Mark”

Theatrical but measured, he kept his crises simple: “I destroyed that one collage I was having trouble with. I ripped it to shreds, murdered it so I would never be tempted to try to save it. The other turned out better, but as I look at it, I can see that it needs something––a little something, but what that something is and when it will come to me is anyone’s guess. Love, mark” and his triumphs brisk: “I’ll be there. I solved the collage problem. Now am off to make paper. Love, M.”

Of Madrid, he wrote in praise, “If it rains here, it usually does so at night”––a rhythm that could represent his broader mojo. Let it rain, but after work, after play, and then, shine again.

As his friend of a half-century Charles Simic has written, Mark was always chasing down “cheap palazzos.” The great luxury of the universe, at a bargain. A steal, an indulgence, a secret victory. Mark passed away in November of 2014, at his daughter’s home, two days after Thanksgiving. I miss him most when something is gorgeous. He would have turned 86 next week. Happy Birthday, dear Mark. We are roasting your proverbial chickens.

__________________________________

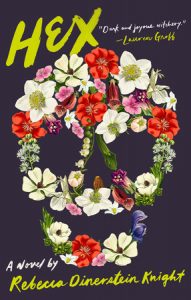

Rebecca Dinerstein Knight’s new novel HEX features a line from Mark Strand’s “The Remains” as the epigraph to its final section. Her first novel, The Sunlit Night, premiered as a feature film at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival. You can order HEX here.

Rebecca Dinerstein Knight

Rebecca Dinerstein Knight is the author of the novel and screenplay The Sunlit Night, and a collection of poems, Lofoten. Her nonfiction has appeared in The New York Times and The New Yorker online, among others. Born and raised in New York City, she lives in New Hampshire.