Remembering Late Nights With Pedro Gomez, Beloved Baseball Reporter

Dave Sheinin on One of the Greats

It was an October night on the East Side of Manhattan. An Italian joint called Il Vagabondo on East 62nd Street. This would have been 1998, maybe 1999, back when we were young and an expense account still meant something. There was a big table of baseball writers. There was wine. There was pasta. There were stories being told—or maybe being retold, but that I, newly attached to the baseball beat, was hearing for the first time. And there was, at a table nearby, a woman celebrating her birthday, waitstaff gathered around singing, cake, candles, the whole deal.

Across the table, Pedro Gomez caught my eye. Head tilted, eyes gleaming, he had a look on his face that said, “You gotta do this.”

We all have crossroads in our lives, at the intersection of time and opportunity, where one choice leads you down one path, and the other, unchosen one—had you taken it—might have changed everything. In reality, I didn’t really have much of a choice here. I was under the influence of both Chianti Classico and the irresistible charm of Pedro Gomez. Either one might have done the trick—but against both, I was powerless. This, without question, was the night my fate was sealed, the night my professional legacy, such as it is, was cemented. From that moment on, whenever baseball people got together, I was the guy who sang and played piano. You know, Pedro’s friend. And I’m good with that. It was Pedro who did this, who hung that star around my neck before anyone else knew about the musical side of me.

He was part-superfan and part-agent—in that he both delighted in hearing me belt it out and excelled at lining up opportunities for me to do so. (On the other hand, I can’t say he was a great agent, in the textbook definition, because somehow I never wound up getting paid for this stuff—well, with the exception of one night in Anaheim.) Pedro knew about my music proclivities before anyone else, and he knew there was a memorable night to be had whenever he could place me within the vicinity of a small crowd, a free flow of alcohol and a musical set-up—a stage, a band, maybe a hotel-lobby piano, or in a pinch, an acoustic guitar. Microphones were optional. And sometimes I could make do with just the crowd and the alcohol—such as that night in New York at the Italian restaurant.

You can probably see where this is going. Pedro made the introductions: “Ma’am, this gentleman here is an opera singer, and he would really love to sing you an aria for your birthday.” Never mind that I was not really an opera singer—nor for that matter a gentleman (I had only studied at both)—and what I was about to do would have never happened had I been sober. But nonetheless I stood up, right there, in this popular Italian restaurant in New York City—let me repeat that: at a popular ITALIAN RESTAURANT in NEW YORK CITY—and fortified by the wine and my youthful hubris and the encouragement of my friend Pedro Gomez, I cleared my throat and belted a show-stopping Italian number for the startled birthday girl. I’m told it was “O Sole Mio.” All I remember is that it was well received, at both tables, plus all the other ones within earshot. There may have been tears in the eyes of the Italian waiters watching from their stations. It may have resulted in the arrival of additional bottles of wine that we didn’t have to pay for. It often happens that way. And I’m good with that.

Pedro hung the star around my neck before anyone else knew about the musical side of me.

It was music that connected me with Pedro from the first day we met. This would have been June 1989, when I drove across the lower section of the country in a Chevy Cavalier without a working gas gauge or speedometer—owing to a digital dashboard that would no longer light up—for a summer internship at The San Diego Union. I had with me a suitcase, a guitar, an address and a name: Pedro Gomez. The sports department had put out a call for a volunteer to house the intern until I could find an apartment, and it was Pedro who raised his hand. He seemed really cool: Cuban dude, great hair. He said I could crash on the futon in his living room. But it wasn’t until I got a good look at his CD collection—R.E.M., The Cure, XTC, et al.—that I knew we would be friends.

A quick word about that San Diego Union sports staff, circa 1989: I would put that staff, in terms of its talent and the careers we all went on to have, against any similar-sized staff in the country from that era. Pedro, just 26 years old, was covering preps. Buster Olney, later of The New York Times and ESPN, was there. Jim Trotter (NFL Network/ NFL.com) was there. Ed Graney (now a columnist in Las Vegas) was there. Mark Kreidler was writing takeouts and columns. Kevin Kernan covered the Padres. Tom Krasovic. Chris Jenkins. Mark Zeigler. Bill Center. Jerry Magee. Barry Lorge. Just a massive amount of talent on one smallish sports staff.

Dave Sheinin playing piano.

Dave Sheinin playing piano.

At some point, early on that summer, a bunch of us wound up at a jazz and blues club in a strip mall out east of town, a joint called Pal Joey’s. There was an old jazz man named Fro Brigham just starting up his weekly gig—trumpet player, raspy baritone voice, beret perched on his head, little bit of a Satchmo vibe. At some point, I must have let on to the guys about my musical background—music major at Vanderbilt, studying as an opera singer, etc. I don’t remember for sure, but I suspect it was Pedro who let the band know there was a singer in the audience who would love to sit in with them. It was, of course, very much NOT true to say that I—a knuckleheaded, 20-year-old college kid who thought he wanted to be a sportswriter, or possibly an opera singer—wished to sit in with an experienced, talented, PROFESSIONAL jazz bandleader and his equally talented five-piece outfit.

But Pedro, though having known me for only a matter of days, had an innate understanding of the most effective way to coax me into this situation, so I was good and lubed up when I stepped up on the stage. I think we did “The Thrill Is Gone” and “Since I Fell For You,” but all I remember for certain is that my showstopper—and even now, 30-some years later, I cringe as I type this—was “Bad To the Bone.” Oof. Yeah, that happened. I may have juiced it with some operatic flourishes at the end. But the thing is, people loved it. The sports department lads. The audience. And especially Fro. He invited me back the next week, and the week after that, and it became a weekly sit-in gig for me the rest of that summer.

I eventually moved off Pedro’s futon when I found myself a room to sublet in an apartment with three UC San Diego coeds. But Pedro and I would be fast friends forever. In the mid-1990s, we wound up at The Miami Herald together, which allowed him to see me perform in an actual opera, in my side-gig in the chorus of the Greater Miami Opera, and allowed me to visit Pedro and Sandi shortly after the arrival of their firstborn, Rio. Somewhere, I still have the picture of me holding baby Rio—a memory Pedro and I, as the years passed, would bring up with awe and wonder as Rio grew into a strapping lefty and blossoming professional pitcher.

“You held him in your arms when he was a baby!” Pedro would half-scream, half-laugh as he showed me the latest picture of the modern-day Rio. “Can you believe it?” It happened pretty much exactly like that the very last time I saw him.

By the late 1990s, we were both covering baseball, and over the next couple of decades he became known as the consummate baseball reporter and one of the most popular and universally respected figures in the sport. I became known as the guy who sings and plays piano. You know, Pedro’s friend. And I’m good with that. It was great to be Pedro’s friend. He was a force of nature, the type of warm personality that drew people in and opened them up. When I was around Pedro, I eventually knew everybody else around Pedro. “Hey [random player, agent, GM, etc.]. Do you know Dave Sheinin?” And Pedro knew everybody. My experience wasn’t alone. This is how it went with anyone who knew him. We were all satellites in Pedro’s orbit.

It was in those early years that I became a serial assaulter of Marriott lobby pianos, often late at night or early in the morning after last call, many times at Pedro’s instigation. I believe he was there the December night in 2000 at the winter meetings when Tommy Lasorda wandered by as I was doing my thing and joined me for a couple of Louis Prima numbers. By the early 2000s I wore like a badge of honor the fact I had been kicked off Marriott lobby pianos by hotel security in nearly every big league city. It was sometimes messy.

Photo by Michael Zagaris

Photo by Michael Zagaris

Other times it was glorious. Such as the night of October 26, 2002, when, blessed with those wonderful West Coast deadlines during the San Francisco Giants/Anaheim Angels World Series, a bunch of us, including Pedro, wound up at the Anaheim Hilton. The Anaheim Hilton happened to be the Giants’ team hotel, though that’s not why we were there. We were there because it had a piano in the lobby with the ideal setup: close to the bar, surrounded by chairs and sofas, minimal security. I was well into my set when someone first noticed a solitary figure sitting and drinking at a cocktail table facing the piano. It was Dusty Baker. Let me back up: October 26 happened to have been the night of Game 6 of the 2002 World Series, and it was mere hours after what was one of the most crushing losses of Baker’s career. The Giants, nine outs from winning the World Series, blew a five-run lead in the seventh and eighth innings and lost. The next night, Game 7, they would lose again, and Dusty’s best shot at a championship would be gone.

Pedro, of course, was the first to go over to say hello to Dusty that night, mostly just to check in on him, to ask how he was doing. Whatever Pedro said, he managed to coax a smile out of Dusty. It would be some time later that I got to know Dusty myself—but at that moment, I was happy enough to be the guy who sang and played the piano. You know, Pedro’s friend. Dusty stayed and listened and hung out for a while, then stood to leave. Someone had placed an empty rocks glass on the piano and stuffed a couple of ones in it—a makeshift tip-jar—and as Dusty passed by, he nodded in my direction and dropped a 50 in the glass. That was different. It sat there all night, and at the end we gave it to the nice cocktail server who had been supplying us with drinks.

There were so many epic nights—some of them involving a piano, other times just a great night out on the town—that they all bleed together in my mind into a chaotic, boozy haze of memory, with Pedro’s big, smiling face at the center of it all. Here at home, my piano, a six-foot Yamaha grand, sits in the front room, angled into the room’s far corner, surrounded by barstools. When I sit at the bench and place my hands on the keys, I’m facing the door and the large window looking out to the sidewalk. It’s set up in that way to be an open invitation to neighbors who might be passing by. Pedro would love it here.

But tonight my hands are stones and my voice a scratchy whisper. I think of all the tunes that have been my go-tos, my crowd-pleasers through the years, and tonight I just don’t have it in me to play them. All

I see is Pedro, elbows leaning on the piano, drink in his hand, shit-eating grin on his face. “Love Train.” “Thunder Road.” “Let It Be.” “Build Me Up Buttercup.” “Like a Rolling Stone.” “Piano Man.” “I Will Survive.” I don’t think I’ll ever play them again without thinking of him.

And “American Pie.” Yeah, especially that one. Everyone always sang along to that one. I prided myself on nailing every verse, no matter how many drinks were in me. But I never spent much time thinking about the lyrics, and tonight they are devastating… February made me shiver… Bad news on the doorstep… I can’t remember if I cried… The lovers cried and the poets dreamed…. The Father, Son and the Holy Ghost… They caught the last train for the coast.

I’ll tell you this much about February 7, 2021: For me, as long as I’m on this earth, that will forever be the day the music died.

__________________________________

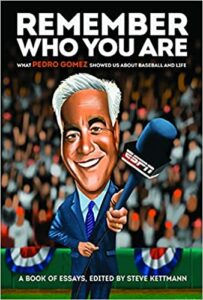

Excerpted from Remember Who You Are by Dave Sheinin. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Wellstone Books. Copyright © 2021 by Dave Sheinin.

Dave Sheinin

Dave Sheinin is an award-winning sports and features writer for The Washington Post, where he has worked since 1999. A graduate of Vanderbilt University, where he studied English and music and trained as an opera singer, he lives in Maryland with his wife and their two daughters.