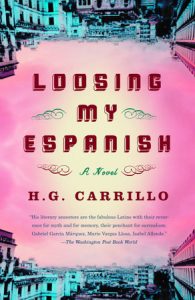

Remembering H.G. Carrillo, and His Marvelous Recounting of Cuban History

Manuel Muñoz Introduces the Late Author's Novel, Loosing My Espanish

“Well you know sometimes you no know you no going to like something until you right in the middle of no liking, Amá will say whether things are good or bad.” This magnificent tongue-twister opens H.G. Carrillo’s novel Loosing My Espanish (excerpted below on the next page), and it’s a sentence that cracks open our narrow definitions and expectations of both voice and style. What would this sentence sound like read aloud? What’s happening in our imaginations as we try to place that voice onto a character? It’s remarkable how easily this sentence reveals how clouded we are by the cultural and racial dynamics that govern how we hear each other when we claim to be listening.

Published in 2004, Loosing My Espanish was part of a generational shift in Latinx writing. Hache (as his friends called him) would have resisted being named as one of those who helped usher in a new dimension to how we were read. He shared a deep reverence for teachers and elders, those Shiny Distant Shores we could keep our eyes on while adrift, and he would have shunned a spotlight that failed to illuminate all those who were still writing on the edges.

The publishing industry has always had a limited understanding of nonwhite stories and Hache was no stranger to the creative frustrations that come about in having to deal with it. It is all the more remarkable that his first novel was one of enviable complexity, relying not on anything immediately recognizable as autobiography but chancing everything on history and the gargantuan task of trying to retell it.

The old way of doing things was to give us a story we already recognized or thought we knew, in a manner that was straightforward, if not outright sociological. Plot was paramount, as was resolution. But Loosing My Espanish wasn’t going to offer that if it wanted to honestly mirror what history was always telling us: you cannot, in fact, ever locate the beginning, middle, or end of any story worth remembering.

Hache would have shunned a spotlight that failed to illuminate all those who were still writing on the edges.

It would take a teacher, of course, to be bold enough to try. Óscar Delossantos, about to be dismissed from his high-school post, decides he will dedicate his remaining lecture days to giving his charges the education they truly need. He’s going to show these young men that the personal is political, and that the great history of Cuba intertwines with the everyday trials of their young lives. The lectures are the novel’s great feat: a narrative device that showcases Delossantos’s eloquence and cadence, speaking Spanish and riffing indiscriminately to his students in a newfound intimacy that will only last the few weeks until the end of the school year.

Compelled to explain as much as he can in little time, Delossantos buckles under the urge to annotate and expound, to divert into the dark tangential corners of history. Soon, he can’t help but reveal more than he really wants to—or even what might be appropriate to his audience. In the great overwhelming waves of history, it is the intimate and the personal to which we must cling. “Why remain las víctimas de la historia,” Delossantos admonishes, “when it’s yours to write, yours to control.”

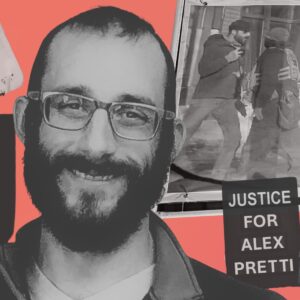

Hache Carrillo, who died on April 20, 2020 from Covid-19, left behind this novel as his only published book. A sizable cache of short stories, appearing in Conjunctions, Kenyon Review, and Iowa Review, will reveal him as a meticulous chronicler of the disorientations, large and small, experienced by those who cannot escape our myopic understandings of race and class. He might have relished the romance of a single arrow thrown up into the literary sky, but we’re left with the longing of what else he might have produced. Vayan, he wrote to conclude his acknowledgments at the end of his novel, a despedida that reads not as a goodbye, but a reminder to go on in the world. Escriban.

–Manuel Muñoz is the award-winning author of two collections of short stories, The Faith Healer of Olive Avenue and Zigzagger, and a novel, What You See in the Dark. He lives and works in Tucson, Arizona.

From

Loosing My Espanish

by H.G. Carrillo

Well you know sometimes you no know you no going to like something until you right in the middle of no liking, Amá will say whether things are good or bad. She’ll say it at the start of something, or in the middle, or long after it’s finished, which makes it difficult to tell when you’ve gotten to the moral of the story. Will things get better? Are they about to get worse? You never know if her eye is fixed on a distant horizon or clouded in some memory right in front of her.

She said it when Joaquín-Ernesto—the Santiago Boy—went through the ice that winter after we moved up from Miami. And again as he began his ascent into sainthood here in what little there is of Cuba in our tiny community in Chicago.

None of us in Troop 227 had seen it happen. It was after Christmas, bright and cold. On the bus ride out Father Rodríguez and our scout leader, Mr. Sáenz, said that the older boys were to keep an eye out for us younger ones, but the moment the doors opened to the wide expanse of Starved Rock, we ran and shouted and shoved at each other like rams; like wild banshees, Father Rodríguez said. All that morning we followed raccoon tracks as they appeared and vanished under dustings of snow. There had been lunch at the lodge and the discovery of an abandoned hummingbird’s nest.

We had been sent to trace the flight patterns of nonmigratory birds when Mr. Sáenz began yelling for us to divide up in twos and look for him. ¡Vamos! ¡Vamos now, goddamnit! Father Rodríguez was yelling.

And later, when we all got back to the city, Mr. Sáenz was crying he never, never, never, never, never lost a boy in all his years.

The wind stood the few long hairs across his bald head on end.

The rose thickets have come up so high over the back fence, and the smell of garbage and urine we had all grown used to over the years has been overwhelmed by the fragrance.

Other than the murmuring that continued long after the Santiagos were led home, the only sound was the icy clatter of leafless trees. Forever after that—because the body had not been found that day—it was easier to focus on the bald spaces on Mr. Sáenz’s head. Somewhere in his eyes he had brought back a jagged hole in the ice just big enough for a boy to slip through, and by the time night closed around those twenty or so blocks where we all lived, we all knew that any one of us could fall into it.

And she said it again, Amá, just last week when she set fire to her kitchen, an act that took with it almost all of what little of Cuba we had here.

Nearly everything saved, wished for, prayed for in that tiny little casa blanca just off of Ashland Avenue that she had said was always and forever in the back of her mind seemed to willingly take to the flames, become unrecognizable, until nearly everything Amá had ever wanted was either altered or gone.

This morning, after spending hours at the insurance office, Amá and I went to her house. And even though we had spent the past two hours itemizing objects and appliances and books and glassware that had been lost or damaged, neither of us expected to walk into the kitchen of Román, Julio and my childhood, where we all had eaten the meals and told the stories and sang the songs and mucked the boots and did the homework, gone. Clear through the upstairs, all had given way to a crow caught in a hot gust of air above us.

The wooden back porch has been burned away and the sky comes in so now we might as well have been sitting in the garden. Amá took her place as always at the head of the table and gestured for me to sit next to her. The table’s aluminum frame is still intact, though the linoleum top has melted into itself a little so that the blue and yellow and gray colors now all converge kaleidoscopically. Ay, Amá said smoothing her hand over the surface; it was the first thing she bought when we—just Amá and me then—were still living, just surviving in a small apartment off Logan Boulevard.

She apologized there was no coffee, and then laughed saying that it was something she had as a girl dreamed of: being the lady of the house who always had coffee and silver to serve when family or company came to visit. We laughed until we just sat looking through the hole that had been eaten through the wall to the garden.

The delphiniums are so lush, plentiful and purple for this time of year you can’t see more than a foot into the yard. The rose thickets have come up so high over the back fence, and the smell of garbage and urine we had all grown used to over the years has been overwhelmed by the fragrance. They encroach so far—as if to make a canopy—there would be no way of telling there was anything else there, if from where we sat you couldn’t see the peaks of three or four elephant ears, gigantic, seven or eight feet tall, in the air.

She told me, like always, all she did was set the rice on to boil. And then, like usual—Dios mío—she began to pray. She included the names of all of the saints she could think of; the week’s numbers for the loteria; and the soul of Abuelita; and the pope who she swears must have at least a little Cuban blood; and the dearly departed Madre Teresa; and the world’s starving children; and for her only sister left, tía María-María, and her husband, tío Néstor, and their daughters—cousins I only remember meeting once when we were all small children—Julia y Wilma in Santa Fe; and for the sisters that Amá has always said that she has had the good fortune to adopt and be adopted by since leaving Santiago for La Habana, and then La Habana for La Habana Pequeña, and then leaving Miami for Chicago; said she has always considered herself lucky to have had two of the most magnificent mujeres to walk the face of the earth—las doñas Liliana y Cristina—as friends without whom life in this country would simply be unbearable; and for the three boys they all raised together—Román—El Blanco—who she said they would all see on the television one day, y Julio—El Negro, Román’s gemelo, doña Liliana’s sons though they have different last names—who she said she wasn’t sure what it was he did but however she was quite sure whatever it was would one day change the course of the whole world; and then of course for me; she always prayed for me, her own whom she could not be more proud of; and, she said lowering her eyes, she even prayed for Juan Ocho, who did nothing for her—she reminded me even though she said she was certain that I already knew—that Juan Ocho and his trumpet playing did nothing at all—nothing for her and certainly nothing to her—except give her a boy with the same castellano hair that any woman—no matter how good— might have fallen into, which is why, she said, when she prays she never includes herself; it just wouldn’t be right.

And maybe today I’ll know something, maybe I’ll be able to say something like: But you see, señores, this is how myth is made—from just these shards—this, this is historia . . .

Gone now are the pictures of the sea-green dress—the one made with the exact color fabric as doña Liliana’s eyes— that Amá and another girl had to sew her into; no zippers, so that her attendants at a coming-out party would say that it felt like they were holding an angel, they say, like a cloud, like nothing in their arms. Singed, after years under gilt and leather covers. Their edges and centers melted into the plastic sheets leaving behind a gloved hand and the famous swan ice sculpture that stood nine feet high and the fountain that sprayed pink champagne.

Gone too is the picture of Juan Ocho and his wavy castellano hair and his shirt opened to his trim waist and his ojos malos the color of asparagus water that no woman could resist no matter how good.

Left is the lady’s hand door knocker: her fingertips gently resting on her tambourine, placidly, calmly, as if nothing happened, merely caught in una siesta between fiestas. Also, the aquamarine brooch in the shape of a dragonfly doña Liliana is said to have thrown away because the clasp was loose that Amá or another of the girls working in the grand house in El Vedado is said to have pulled out of a wastepaper basket. And the gold-rimmed plates doña Cristina managed to get on the plane with her—a setting for seventeen and a quarter—though mostly broken. The credenza and buffet in the dining room stand steadfast though warped into blackface caricature. Though gone too are the photos of tío Néstor y tía María-María at the Santiago bar where Néstor and Juan Ocho’s band played: Los Americanos—merengue, rumba, samba, jazz, boleros of heartbreak, loneliness and betrayal—everyone used to wait all week just to hear them play; Amá says they were so good they almost had a record contract, says they were set to tour South America before Castro.

Upstairs a charred box still holds the silver cuff link doña Cristina says Amá stole from Juan Ocho with the hope doña Liliana could find someone who could put a spell on him that would bind his feet and keep him from straying.

Fisted into a cinder was the packet of letters addressed to Amá, but meant for all of us, from my prima Carolina, still in Cuba. Like plaintive songs caught in an ever-constricting throat, they once read of long-ago and far-away: Mireya, you know I haven’t had a new dress in an age; Mireya, you have no idea what it costs to get any lipstick, let alone a good one and you know the closer I get to thirty chances slip by me; Ungüento, Mireya, send ungüento in a hurry, with a quickness; Send the one like the one like we see in the ad that comes over fuzzy from America on the tiny little television a girl down the hall from us has . . . send the one that cools the burn and eases the pain like they say, for I work now, we all do . . . in the fields all day with a machete, like a man or an ox . . . no, querida tía, like a burro . . .

The gutters lay skeletal around where the back of the house has been eaten away, though every math test Julio, Román or I had ever taken, every paper we had written was preserved by a fallen mirror.

The baby shoes doña Cristina had bronzed when Román must have been all of thirteen were steadfast, though the door we had stopped open with them—the door to what had been the room Román, Julio and I had shared—looks as if it had been snarled and slathered by a toothless black mouth.

We both sat there, Amá and I, wishing for cafecito in perfectly crafted, painted china cups with matching saucers. Amá looked around at what had been what for so long she told everyone was the reason we had left Cuba and said, Well you know mijo, sometimes you no know you no going to like something until you right in the middle of no liking. And although we were staring at smears that trace the carpet along the hall to the sewing room that Amá y las doñas had fixed so nice, I knew that she was talking about both that moment then as well as when we first came and lost the Santiago Boy; and the moment we set foot in La Habana Pequeña, as well as the first sentence that I heard Amá say in English. Sometimes you no know you no going to like something until you right in the middle of no liking.

And maybe today I’ll know something, maybe I’ll be able to say something like: But you see, señores, this is how myth is made—from just these shards—this, this is historia . . .

Escuchen señores—hombres jóvenes; all of you who have sat in these seats over the past several years; mensajeros del futuro; mis iluminadores, mis casas, mis escuelas, mis corazones, mis playas; mi sentido común; mis yucas locos—I forget all the names that I have had for you—Shiny Distant Shores. Even yesterday’s too long ago, a fever-dream broken into floes of hunger and want and then more want, it is so far away now.

Óiganme. You have no idea, given how ill-disposed I am to looking at myself in mirrors, how surprised I am to find myself—in the rear- and side-views of my car, in the glass awards cases that line the halls on the first floor—like now, still talking to you. Sometimes to years of you long gone. And surprised to find that what’s being said about me these days—that I have begun to occasionally mutter to myself—may be true.

But it is strange how something that I have always done—rehearsed my lectures, made lists, figured out what comes next—is now an act of self-consciousness, that now what’s in the past has made me appear to be something other than what I am.

I’ve only thirty-four more of these opportunities, and I’m finding time comes flying back on me whether I want it to or not. All of a sudden, I find myself mouthing years of attendance rolls, record books of grades, notes for lectures that now will probably never be given. My muttering. Muttering, they say, as though I have not always been trying to make these corrections; as though I haven’t been always thinking them as loudly as I could these things that they say that I now mutter; things I believe they believe I say as if I have no idea what’s coming out of my mouth anymore.

Ay but in all fairness, I’ve done very little to be understood.

So thirty-four more times—if we take out the days we’re off for Easter—there are, mis hijos. Only thirty-four more opportunities to prepare these lectures and stand in front of you in classrooms that have become all too familiar, so much like home, mis chicos queridos. And I finally have some answers to some of the questions that you have asked me, now.

Traveling past the nurse’s office to the principal’s office, Father Rodríguez’s and Father McMillan’s offices, I wave, tousle the heads of a couple of passersby, congratulate a victor on the field for his recent win, answer quick questions about assignments due, agree to meet about an essay, a letter of recommendation. He’s very affable; Likable . . . all of them like him . . . they all seem to learn from him, everyone says so; a mí me gusto mucho; Been so good to all of mis hijos, I’ve overheard mothers say when they were certain that I was within earshot. More than once has someone’s father come to me after a soccer game to say that he’d never thought that he’d see the day that his son could take charge; take the ball down the field that way; once it was described as if in an afternoon a son had shed all of his boyhood, run it off down the field and appeared a new and different person. Wonderful pedagogical skills, highly organized, very demanding although his students all seem to love him, Father Rodríguez has copied each year from the first of my annual assessments as if nothing could or would ever change; or as if the only possible change that could occur is that eventually I would sit in his place copying the same words into the annual assessment of someone who had once been my student.

Each morning as I pass the portico into these hallways on these last days, these final days, I wonder how I haven’t noticed the din that pours out from the cafetería: a howling—like caged animals—the murmuring grunts, the flung cereal boxes; the clatter of cutlery. Or the smell that is not all that different from the locker rooms as I pass under the cupola by the large stained-glass window that looks out over the bell tower, the green, the parking lot and the play fields.

There have been many times over the years that I have been tempted to simply sit in the window niche on the second-floor landing under the cupola, and rather than going on, just watch the dust particles ride the sunlight, watch students cross below me scurrying, already as busy as the men that they will grow up to be, taking on the roles that will one day make them feel important, satisfied, safe, trusted.

It could be that it is this building. That despite its disrepair—the cracks and leaks, the peeling everywhere, the broken lockers for which there is no money; there will be no money coming in; nada, nada; nada—the something grand, the something particularly ambitious that made the immigrants who came to this area nearly two hundred years ago to look back to a medieval France, and an ancient England, a Renaissance Italy with hope enough that they pooled pennies earned at factory jobs and the domestic chores of others a little at a time in collection baskets still lives here. Years ago, when Julio and Román arrived from Cuba by way of Miami with las doñas Cristina y Liliana, Amá thought it important to see to it that the boys were acclimated to their new home: she took them to the lake, made sure they had new uniforms, showed them how to take the bus in the rain instead of the route that she laid out for us. The first opportunity that I had to show them something on my own I took them to the cupola—the same way anyone who has gotten to be a boy here and shown someone else—stood them on the opposite side from me and showed them all I had to do was whisper the words comemierdas and putos for them to hear. The three of us spent more than a half hour their first day on the cracked mosaic of the Sacred Heart calling each other moco, estúpido, chica, until Román or Julio let go with a belch that resounded the dome and peeled us off running in fits of secret laughter; as if we had gotten away with something that no one else either knew about or could recapture again.

And I want to tell them, the boys, to hold on to it, this moment, it goes away as if it were never there at all, but I never do.

Sometimes it may just be enough to watch, boyhood, I often want to tell my colleagues as we’ve whined about test scores, curriculum, textbook choices and the like into the fretted muck that we like to call faculty meetings. And although I have never bothered to do it yet, lately I’ve come dangerously close to asking them, if like so many things that thrive on their own, do the boys really need us the way we think they do, the way our egos tell us they do, forcing them to do the things that we demand of them as if we know any better? It has been a long time that I have wanted to take each of them, one at a time, by the hand to this window and simply say, Mira. And then watch them, my colleagues, see everything that they had hoped for, everything that they had dreamed was already realized right before them. Even boys have their seasons, I’d say: in the winter, they leave their houses bundled for the cold, and halfway, something switches them on high and they’re sweaty and shoving at each other, coats open, gloves lost. I’ve a cardboard box filled with scarves under my desk that no one will claim; as soon as the weather starts to get warm, they fill up with a harmless venom, boys do, that sets them on a fidget that either makes them want to tell you an elaborate lie, smash something or build something out of nothing. And I want to tell them, the boys, to hold on to it, this moment, it goes away as if it were never there at all, but I never do. Never say it to either my colleagues or the boys.

Instead, for years I’ve left the echo of the cupola with all its dust and smell of oil soap, rounded the gritty terrazzo steps and headed toward the end of the hall on the third floor, the furthest from the stairs, where all the new teachers, younger teachers have been assigned since I’ve known of this place.

I suppose all I had to look forward to was moving to a lower floor in the succeeding years; closer and closer to the vestibule a little at a time had I not been shown a quicker way out.

And—not unlike the first time that I came to this school, and Amá handed me my lunch, straightened my tie, used her saliva and finger to rub away at the corners of my mouth while she told me that this was one of the moments in her life of which she was most proud in spite of herself because she always wanted me to know that my successes as well as my failures would always be my own—I cross myself, kiss my knuckle, inhale deeply, push down the battle in the pit of my stomach y . . .

Escuchen señores. Óiganme todos, as you have all heard at this morning’s assembly, this school will no longer exist as it has during the past hundred and three years and I will no longer be a fixture here. We are the last school in the diocese to go coeducational because of the lack of funding, they say, and you now know that I am not listed among the teachers who will be returning next year to meet the challenge.

Challenge, Father Rodríguez has told me. That was the word he used, challenge.

Ay, what challenge, señores?

But I suppose that many of you already knew this. You’ve heard the rumors. And I suppose that this kind of education—boys being taught to be men separately from girls being taught to be women—has been arcane for a while, a thing of the past, and it’s time for some of us to move on. Some of you will graduate, others will move on to your senior year though none of you will be able to nudge your little brothers and say, Take Delossantos’ class.

I’ve heard you say it. I’ve heard so many of you say it.

I know an entire generation of you have been telling each other, He’s an easy A, a pushover.

And I suppose it’s true. But someone should be easy on you; someone should clear a path for you. After all it is an awfully indifferent world, a dangerous world, a strange world that we send you out into with little more training than an infant would have to take the helm of an inflatable life raft.

And of course, there are those of you who I have let leave—years of you have passed through here—with me biting my tongue.

Well, no more.

You are my last. Not that I had had any plans of abandoning my position, no. But still, you are my last.

I’ve heard the chisme—like old ladies, you are—in the cafetería, on the playground, in the hallways for weeks now all I’ve heard is that so-and-so’s mother told someone’s uncle’s cousin that Delossantos was getting sacked; he must have murdered someone, or embezzled from school funds.

And it is true, that it was no coincidence that I accompanied my mother to the insurance office during this morning’s special assembly. I suppose the good Father Rodríguez wanted me to save face in some way or another. Though my absence had nothing to do with the freshly inscribed message above the third urinal in the third-floor boys’ room, which as a result of poor grammar leaves me somewhat befuddled. In the event that the author is in this room, stand corrected that were I to have a predilection for canines I could joder perros; or might have jodido perros; or were it the beginning of a poetic assertion, the rather flowery Mr. Delossantos, que jode perros, may have made a rather lyric opening to an ode or ballad on the theme that could have easily wound its way down the line of sinks and back behind the last stall where you all hang out of the window to sneak cigarettes even though you think the faculty doesn’t know about it. As it stands—Mr. Delossantos era joden los perros—it is not only untrue, but may be an indication that I have failed those of you who have come to me seeking help with your Spanish grammar.

Señores—los hombres apacibles jóvenes que van a heredar la tierra un día as the world’s bankers and accountants and businessmen and garbagemen and husbands and lovers and doctors and lawyers—every morning for the past twenty-two years, I’ve cleaned my glasses, knotted my tie and after toast and coffee and a cigarette, stood in front of rooms full of you tracing the generosity of a Spanish queen through to the Declaration of Independence; the launch of the Americas; and the trajectory of the greedy fists of the English, Spanish and Portuguese slave traders as they were hurled over centuries into the faces of the unsuspecting of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, who knew nothing about baseball and apple pie, or American History.

As freshmen most of you had me for World History; American Government when you were sophomores; some of you have been in my homeroom. I have helped coach the soccer team, and I have tutored many of you through Spanish and English exams. I have waited for this moment. This class—Histories of Latin America: From Colonialism Through the 1960s—is an elective; so all this semester, I have assumed either you want to be here or could fit nothing else in during fourth period and need the credit to graduate.

When Román, Julio and I were boys, by flashlight we’d read to each other in hushed whispers tales of marauding pirates and invincible sea monsters, and ghost ships that flew through the night.

And so far this semester, we have established the dollar amount fixed into Cristóbal Colón’s hand and computed its value in today’s market, the cost of the ships included. We’ve speculated on what acts of love, what promises of romance, were exchanged between the queen of Spain and the Italian.

Even though after examining the Delacroix portrait of the dashing Colombo and his son at La Rábida, as well as pictures of the Randolph Rogers alto-relief bronze doors at the Rotunda in the District of Columbia—an entire district he gets—and pictures of the paintings of Colombo at the museum in the Vila Baleira of Porto Santo, none of us has any idea if the Genoese Discoverer was really “tall of stature” or possessed “an aquiline nose” or “blue eyes” or had a light complexion, or had white hair by the time he was thirty though blonde as a child, because none of the images we have of him were created during his lifetime as is written in history books. And what do we know about Isabella and the rather homely Ferdinand? We speculated on the beautiful Spanish woman in The Assumption of the Virgin and wonder if she is the patroness of northern European artists of her time like Miguel Zittoz y Juan de Flandes, who were renowned for their infinite attention to detail, yet really know nothing of her beauty.

However, once we’ve conceded a romance we’ve also committed ourselves to a mustard field near El Cerro de Cabeza de Toro.

¿Por qué no?

A mustard field in full bloom, where under the watchful eye of La Virgen de Trujillo, the Genoese Discoverer chases his beautiful, regal mistress, his patroness. There are those who would say that she was girlish in her coquetry, hardly what one would expect of the sovereign of Iberia. There are those who would say that her hair was raven-colored.

Does it matter if there were mustard fields in bloom in Trujillo that spring before the Genoese set out? No, I’m not even sure if mustard grows in Trujillo.

Pretend, imagínenselo.

Imaginen.

When Román, Julio and I were boys, by flashlight we’d read to each other in hushed whispers tales of marauding pirates and invincible sea monsters, and ghost ships that flew through the night. And for each unearthly soul that flung itself out from the sea to take revenge, to right an injustice, to yowl its indignation, Julio would stop us to ask if it was true; if it really happened. Did the captain dance the mizzenmast, sword in hand, as flames engulfed the deck; could a galleon really hold the wealth of an entire small kingdom? It would seem silly now, I would be hesitant to ask either of them now if they remembered the dark, remembered the slightest sway of wave that we could set down the densest, darkest of tributaries into the roughest of waters out to an open blank. In fog, we read, ships called out every two minutes with the clanging of a brass bell to hush the roar of that eerie silver-gray light of possible oncoming danger: a head-on collision that would slice the more vulnerable of the two between stem and stern, send hundreds scattering like grains of rice against a polished black floor.

¿Verdad? Julio would stop us and ask. A desperately incredulous ¿Verdad? for each maiden and maidenhead, and ¿Verdad? for every moment that caught him wide-eyed and openmouthed, thinking, Who knows this, who saw this, who lived to tell?

And if tomorrow I were to show up downtown at the actuarial firm where he works with its long floors of men in shirts and ties sitting in cubicles and was able to tell Román apart from anyone else so as to ask about Julio’s doubt and his own anxiousness to Go on, Go on, Vamos—It’s about the story, he’d bark back across the dark of the little bedroom we shared in Amá’s house as boys—I wonder, señores, if he’d say the same thing now in response to where your textbook reads that that year—the year the Genoese sailed—the mustard came up purple; and add, fields and fields of purple causing a luster in the queen’s eyes that allowed the Genoese to know what she was thinking before she ever said it.

It’s a romance we speculate, history, a fiction.

__________________________________

From Loosing My Espanish, a novel by H.G. Carrillo. Copyright © 2004 by Herman G. Carrillo. Published by Anchor Books in paperback and originally in hardcover by Pantheon Books. Reprinted by permission of Stuart Bernstein Representation for Artists. All rights reserved.

H.G. Carrillo

H. G. Carrillo’s work has appeared in The Kenyon Review and Glimmer Train, among other journals and magazines.