Daphne Athas died in Chapel Hill, North Carolina on July 28, 2020. Most of her friends were unable to mourn Daphne together because of the pandemic. In November 2021, Marianne Gingher and other friends organized a memorial service for Daphne at UNC. Here are some of the tributes delivered at that service.

–Thanassis Cambanis

*

THE USUAL INEFFABLE

Alane Salierno Mason

I am a professional enforcer of clarity, but my mentor and one of my life’s great loves was someone I only ever half understood. Her name was Daphne Athas, a second-generation Greek writer of both fiction and nonfiction whose moment of professional glory—a TIME Magazine “Best Book of the Year” and Cosmopolitan Book Selection (!) in 1971—had already faded into the distant past by the time I first had her as a teacher in the fall of 1983 or maybe 1984. She seemed to have stopped writing or publishing fiction since Cora, in 1978, her last book with Viking, which I suspect had not sold despite critical acclaim. Not that this was anything that interested us as students, we didn’t care much about our teachers’ writing careers but only about what good they would do for us. (I’m thinking of a well-known writer who told me not long ago that a student had said to her, “Oh, do you write too?”).

Daphne Athas was part of a triune of writing teachers in which she had the least authority. Doris Betts was more famous, still published by Knopf, a regal figure in Southern letters. Max Steele had published stories regularly in Harper’s Magazine, and had collaborated with George Plimpton in Paris in the 1950s on the founding of the Paris Review, (which he made sure you knew), and was a man, albeit a gentleman, and the chair of the department, and knew how to use both hilarity and insight as tools or maybe instruments of control in the classroom.

Daphne was soft-spoken, not Southern, thought elliptically, hated the presumption of authority, and taught a class on nonsense. Many of her students found her go-anywhere trains of thought terrifying, fearing that not-understanding meant they were stupid. Others of us found it thrilling to let go of work-a-day processions of words and to scramble after some more elusive and intoxicating idea of meaning.

Other teachers seemed to have in mind a Platonic ideal of writing that it was their sacred duty to instruct you in; you would be graded, gently for the most part, on how close you got to that ideal. They were Americans to the core. Daphne touted her authentic “Greek-ery,” celebrating her immigrant father who, arriving penniless, got himself into Harvard. She was Socrates, Lucretius, Heraclitus and Aristotle all rolled into one, with a dash of Epicurus—she seemed to see writing as a wild experiment, a voyage out of The Odyssey, on which you never knew what fascinating monsters (but she would not call them monsters) you would meet, or whether you would get to your destination. And the destination was hardly the point. Certainly she had her own idea of who would end up feeding the fishes but she never elevated her taste and judgement to a universal ideal. She would later tell me she didn’t believe in “good” and “bad” writing—a terrifying credo for the young editor I was when she said it. But she responded with a literal squeal of delight—a “wheeee!!”—whenever a passage of prose or poetry spoke to her ear. She valued surprise, enthusiasm, unpredictability—a sense of music and rhythm, a sense of being pulled on an ocean current across a wine dark sea.

She was free. She seemed to live her life exactly as she chose. Conventions of femininity didn’t matter to her at all. People saw her as a person of indeterminate sexuality as she rode her old bike in her old poncho.

And she had gone places. She had hitchhiked to Mexico as a college girl in 1941, had assisted the war effort in London, traveled frequently to Greece, her father’s homeland, starting in the late 50s, and, after stopping in Moscow to visit Red Square, taught in Iran in the 1970s. There she’d had an unruly classroom, perhaps unaccustomed to a female teacher, and she’d called the ringleader of the boys up to the front of the class and in that soft voice of hers, proceeded to humiliate him with questions he couldn’t answer. After that, the class were like birds eating out of the palm of her hand. I don’t know who enjoyed that story more, she in the telling or I in the hearing. She wanted us to know that despite that soft soft voice, and her general spirit of tolerance, she was no pushover. She was fearless, intellectually and otherwise. She was the least provincial of any teacher I had at UNC or elsewhere.

And she was free. She seemed to live her life exactly as she chose. Conventions of femininity didn’t matter to her at all. People saw her as a person of indeterminate sexuality as she rode her old bike in her old poncho. Her strong features had become more pronounced, eccentric with age. She didn’t give a damn. But she was concerned lest her being unmarried cast some sort of pall on suspicion on her most devoted students, if they were too frequently seen with her outside the classroom.

Beyond that, she was confident in her own brand of womanhood, even saw herself as a bit of a femme fatale and a flirt. Getting married and having children “was not her bag,” she told me, in the way these things were defined in her day, but she was not dogmatic (as some writers have told me their professors and editors were) that hers was the only true path; she thought the younger generations had more leeway to define roles as they wanted them, and she was glad.

It was the Reagan era, the beginning of the great conservative retrenchment. In the 1980s, sororities at UNC were still passing candles around in ring ceremonies to celebrate girls’ engagements (maybe they still do), and many of my female friends were already worrying about whether they were going to have to make a choice between career and family. The media was full of scare stories about career women who regretted that they had “forgotten” to have children, that they had waited “too late.” Daphne modeled a life that was not bound by those (or seemingly any) expectations—one that was not lonely or frustrated in her domestic solitude but completely self-determined and whole. Her model of freedom became my lodestar—I wanted to be Daphne when I grew up.

But growing up for me meant coming to New York City where independence was a fetish but self-determination was hard. After four years as the glorified publishing secretary that an editorial assistant was in the late 1980s—when assistants typed all the correspondence, before editors had desktop computers, and a self-correcting typewriter was the great liberation from LiquidPaper and Correct-o-Tape, and you just hoped your boss would abandon using the Dict-o-phone, an anachronism even then—I went on forty “informational interviews” to try to get promoted to editor.

I was considering the leap to a job teaching English in newly post-Communist Prague when, finally, I had the pivotal interview. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, among the last then-standing of the great publishing firms founded in the decade after the First World War, had just been sold to General Cinema, soon to be renamed Harcourt General, then Harcourt (the trade publishing division ultimately part of HMH, recently bought by NewsCorp). The bow-tied editor-in-chief of then-still HBJ was Cork Smith, discoverer of Gloria Naylor and Carolyn Chute and Thomas Pynchon before being ousted by the “bean counters” at Viking. His previous publishing job at Ticknor & Fields, another name in the great cemetery of 20th century book publishing, had evaporated while he was on vacation. Eric Ashworth, a great agent who soon died of AIDS, called him “the King of Fiction.” Near the end of an interview punctuated by his smoker’s cough—he might even have been smoking a pipe—Cork looked up from my resume, over the top of his black rimmed reading glasses, and asked: “I see you went to UNC, did you ever come across a writer named Daphne Athas?” My eyes unquestionably lit up. Daphne! I admitted she was my North Star and mentor, that I considered her a friend, and we kept regularly in touch.

I didn’t know that Cork had been Daphne’s editor. In fact, it might have been that his firing had something to do with the fate of Cora. But Daphne had given me the magic key. After a couple more interviews at HBJ, including one with Peter Jovanovich himself, and a lunch with Cork (I think a lunch was part of the interview process, to show you could handle the social requirements of being an editor), I got the job.

In New York, from the fire-escape overlooking my landlord’s fig tree in the Brooklyn of the early 1990s (not yet the literary “Brooklyn” of today), I wrote Daphne long letters full of doubts, I’m sure, about every choice I ever made. It was a lonely time. She wrote back extraordinary long handwritten letters of sympathy and encouragement (letters now lost, to my dismay, in a flood in the basement of Norton’s office building), of which I have only a few fragments I typed up for a Daphne-encomium in a North Carolina literary journal some years ago:

Am I inveighing you to digest the autumn of the first (second? Third? Fourth? Fifth?) realization of the conundrum of the literary life? Not limited to editing, but to writing as well. Not finding any good scapegoats either, except the entirely neutral one of money. Money, the bottom line, is not to blame. Only people’s ultimate choice for money. Spurred on by the corporate pressures. It is very hard to live in this world filled up with people crushing each other for advantage.

But in this world not only is the question one of money, it is also one of influence. Influence enters the realm of mythology… Influence is when the “community” buys the propositions of certain people… This is the way, as you know, the mythology of winners is perpetuated.

You have now entered the realm of mythology. You have entered the marketplace where people listen to you. You have some influence. In your place in the pantheon still money talks. You and they need your books, some of them, to make money. And you need to be free enough to publish the work you know to be good in your vision of excellence. The books that move you. And the challenge is to balance these. To not be dragged down and drowned by a universe in which key players can no longer be moved by literature, only by the possibility of money return. It is fortunate that people (some) do read and are moved. Although a multitude think they don’t count. They do. I know it, and you do, too. Somehow you must with your left hand make money for your employers and paddle your own canoe, which is filled with dreams writ large. Is it possible? Of course you are at the heart of the Mammon factory, and when the product is written by seers, dreamers, and jokers, as well as nifty, thrifty, capable opportunists and merchants of words for paltry purposes, well, it is easy to be swamped and then drowned. Does this describe the source of your discouragement?

It does take strength to live without losing your sense of values, and all the more, I think when you’re successful but feel fragile.

It is easy for me to posit the situation, if I’m right. I would do anything to prevent you from being discouraged. That’s why, although I send you this Paperbacking of Publishing article [a great piece in The Nation by Ted Solatoroff in 1991] I do it on a day when the squirrels are nibbling with lifted ears, when the breeze has come up just enough (it came up as I was writing this) for me to know it as a grand breath, and when all the antennae beyond money, opportunism, and the small horizon of small minds are lifted beyond infinity. It is easy for me, pounding on this typewriter to you, as if enticing you to hear a different beat, to say throw it to these winds if it isn’t good or big enough for your view of books…. Anyway, don’t lose your vision… There are many ways to be an editor. And you are in a good position to find them… The best you can do is to exert your influence, and that means your freedom….

My God, how could I have been so fortunate. How could I not have read and re-read this letter every day of my working life since? Not for the practical advice—there was no practical advice, the pile of manuscripts was just as daunting day after day, the hailstorm of small tasks just as constant and distracting, the art/commerce too tidy when the requirement is both/and, the idea of “influence” terrifying then and now (and if there is no good or bad writing, how on earth to choose?), mythology no help at all—but for the love in it, which I cannot now read without tears.

So articulate a love, such generous freedom.

Her orbit of freedom was so strong that for decades afterwards just setting foot in North Carolina, especially Carrboro, where she lived, made me feel freer than elsewhere. I loved sitting on the slate porch of the cabin she had built herself, by hand with friends, in the woods, smelling the leaf mold, eating one of the bananas she kept for breakfast, and I would often spend a night or two on the low cot across from the computer table in her spare guest room/office, where the sound of the rain or falling hickory nuts on the tin roof made it seem the farthest extent of the planet away from New York City.

As I struggled to get my footing as an editor, Daphne mentioned how much she admired the list of an editor I had never heard of, Elizabeth Sifton—the literary fiction world being its own kind of bubble, I hadn’t really heard of any of the great nonfiction editors. But Daphne read nonfiction as voraciously and enthusiastically as fiction. And though I never met Ms. Sifton, Daphne’s admiration reassured me and gave me another notional role model when Harcourt General fired nearly everyone in New York and I was offered a job as primarily a nonfiction editor at Norton, where I’ve now worked for nearly 30 years. I had not yet read much nonfiction out of school, and probably thought in a bigoted, product-of-creative-writing-program way, that less fun and less depth was to be found in nonfiction than in fiction, but if Daphne found nonfiction work to admire, surely I could and would, too. And I have.

I think she would have found value in whatever I did. She found value in living, not just a passive being in the world but in a kind of sustainable mining of it for thought and conversation. That is what writing was for. So her novels and essays spilled into letters, thousands of pages of those rhapsodic, exploratory, sometimes indecipherable letters in arabesques of prose that she sent to the—how many? A dozen or so?—students who stayed in touch over the years. “Stayed in touch” being too anodyne a formulation. Returned to her as if to the intellectual and creative mother ship, for filling up tanks with oxygen so as to keep on breathing in a sometimes suffocating world.

I think of her whenever I consider the big tides of history and culture on which we paddle our very small canoes.She was fascinated by character, grooved on how it was shaped by history and time and circumstance, hence the necessity of knowing about everything in order to understand it. It worried her, politically and morally, that her notion of character had, she felt, become unfashionable. She didn’t like the shortcut of signaling character with historically real people about whom readers already had opinions—this was the basis of a friendly argument she had, jousting, with student Randall Kenan for well nigh a decade. She didn’t give a damn about money but respected the reality of it and resented that the university had hardly paid her two nickels and never given her tenure in all the decades she had been there. The women in the program had been paid a fraction of the salary of the men.

On her 95th birthday, an admirer brought her a balloon. I was there with Randall, who knew it was her birthday, while the timing of my NC visit had been entirely by chance. It was clear I could not stay under the hickory nuts this time; she really was old, and couldn’t tolerate too much disruption. A visitor the day before had already tired her so that she had, unthinkably, deferred my stopping in on her. Yet once we got there, she and we couldn’t stop talking — she pulled us back in every time we tried sensitively to leave so as not to wear her out. She was having fun! We talked about what, god knows, about everything. But it was the balloon that captured it all. I wrote her a huge long letter about travels afterwards and when she did not reply for a long time, and when she did, wrote only of the balloon, it did seem her mind was beginning to drift. But only sometimes. We argued over email about whether the balloon had been red or green. And when I sent her some sort of edible arrangement for her 96th birthday in 2019, it too came with a balloon. She wrote:

I put the new balloon on top of my refrigerator and it spent the night silently waving and weaving in the small air which has blown one way and another softly through the heaters and registers.

Doesn’t that remind you of the Keats’ poem, which promulgated, T.S. Eliot’s poem “I grow old I grow old. Shall I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach? I can hear the maidens singing each to each, but I do not think that they shall sing to me.

It was my surprise actually to find out that that poem is only a quarter of what T.S. Eliot actually wrote in the whole work. Check me if I’m wrong. I’m such a victim of tinnitus that I do not get everything correct in fact and order. I add or subtract too much at my own will.

My thoughts are slow, but nowhere as slow as my arthritic fingers. However, I am very fond of my tinnitus.

I get up. I get up. If I don’t get up, I’m afraid I’ll never rise again. I am not a a bunch of tulips waving in the wind. and sinking in the snow to dry and later wash away

Blow on, O wind and rain,

Enjoy each moment as you can!

In other words you have sent me an entirely new balloon to compete with the green balloon which I have written you about. I had made the green balloon such a presence that I refused to kill it by blowing it up and bust it with a loud explosion after so many MONTHS I’ve kept it

It is presence against reality. The red balloon is alive.

I hope you understand what I am saying. Because I am so deaf in real reality, the existence of these two creatures have expanded my ideas and ideals.

Can I please be Daphne when I grow up? When my mind starts to drift, can it drift so eloquently, bobbing like a balloon on currents of air, or on water along those channels that she dug out for us?

I thought she would live out of sheer curiosity to see the election results in 2020, to see what would happen in the pandemic, but she went out, trapped in a nursing home but COVID free, on the great tide of death. She had written me about death when a close friend of mine died in 1994:

Since time becomes (or is) a positive force in life on earth you may forget him in one sense, as he begins to operate on you in another. The very fact that he will never grow old, will remain young, will maybe keep uttering certain words wot you which he actually uttered, which will in their dynamism, nevertheless, stay always where they are, superseding time and its talent for changing the quality, timbre, and intonation, means that he will become like a landmark, or a statue. Something in one’s private museum… Better still, a wayside identification. Like a shrine. Like a talisman…

And so she is now. I think of her whenever I consider the big tides of history and culture on which we paddle our very small canoes. Her world was “l-a-a-a-r-g-e,” written just so, like “g-o-o-o-d,” its largeness and goodness somehow encapsulated in these lines of a letter she wrote from Egypt in in 1990:

There I stood in my velvet footsteps in the sand, and thew that they, the Pharaoh and his wife, breathed something from three or four thousand years ago. But what was it? Oh, the usual ineffable.

____________________________________________________

On her bicycle heading to campus, Carrboro, NC, late 1970s.

On her bicycle heading to campus, Carrboro, NC, late 1970s.

PUZZLE PIECES

Dana Spencer Francis (aka Dana Danovitch)

My mother, Thalia, was Daphne’s younger sister. For those of you who have read Entering Ephesus, Thalia was the character, “Loco Poco.” In her nonfiction guise, Thalia died in 1962 and I lost touch with the Athas family for nearly 20 years due to misguided family decisions.

In 1981 I met Daphne in Greece. She was on sabbatical there during the 1980-81 academic year. A few years ago, I asked Daphne if she had invited me to come to Greece and she said, “no… you invited yourself to come visit me.” She met me at the ferry in Patras and we retraced the journey she’d taken with her father in the late 1950s when they visited Hora, Pylos and the crescent beach at Voidokilia, which she recounted in her book Greece by Prejudice.

On that trip, Daphne began to impart my Greek heritage to me—my “Greekery” as she liked to call it.

Daphne spent nearly every summer in Greece for over 50 years. She loved swimming and snorkeling in Pylos. She brought her manual typewriter in the early years and later she brought her laptop so she could write. While in Pylos, she would hitchhike or take a taxi up to Hora to visit her relatives, Martha and Ioannis. During those summers, she’d also visit Miranda Cambanis and her family in Paros. And of course, she always tried to break new ground and explore a part of Greece she hadn’t yet discovered.

I’ve been fortunate to visit Greece six times and five of those trips were with Daphne, including a trip with my sons in the summer of 2005. Daphne had broken her leg a few months earlier back here in Chapel Hill, but she rehabbed the hell out of that leg so she could come to Greece and pass some Greekery along to my boys. I have precious photos of her, resplendent in her mask and snorkel, swimming with my sons in Navarino Bay.

I will miss knowing that she’s out there in her hot little shack in the woods, reading everything she can get her hands on.Over the decades, Daphne reintroduced me to my mother’s legacy by providing me with some puzzle pieces that had gone missing. She gave me photos, bits of Thalia’s writing and she graciously helped me locate some of my mom’s friends who welcomed me into their lives and shared stories about Thalia that I’d never heard growing up. To put it simply: Daphne was the most influential person in my adult life, bar none.

Daphne loved Miranda, Stamatis, Alexis and Thanassis Cambanis whom she truly considered “family.” She loved her former students with whom she enjoyed discussing literature, big ideas, movies and current events. She loved teaching at the University, and did so for 40 years, starting at the age of 45. And she loved her little house in the woods in Carrboro.

She could be critical, a trait she probably inherited from her father. Often, after she had ruffled my feathers about something and after I’d licked my wounds for a while, it would dawn on me that her critique of me had merit and had been insightful after all.

I miss our marathon talks, our ”blats” as she liked to call them. We once argued about whether “blat” had one “t” or two. Sometimes, on a Sunday, we’d be on the phone for five hours, jumping from subject to subject, but it was never boring. Never.

The last time I saw her, she had just entered the old Hillhaven Nursing Home. It was toward the end of January 2020 and COVID was beginning to emerge as a news story. I came into her room and she was sitting up in bed wearing her red visor and reading a copy of The New Yorker. MSNBC was blasting at high decibel levels because of her poor hearing.

“Daphne, what’s new in the news?” I yelled over the din.

“I don’t know,” she said. “They’re talking about some kind of world-wide pandemonium!”

Oh, if she’d only known.

On July 28, 2020 I got a call from a hospice worker telling me that Daphne had passed away. I called both of my sons to let them know. I couldn’t reach Eli right away, but I did have a brief conversation with Jamie. I had to cut our call short due to a work commitment that evening. When I was finished with work, I found a thoughtful email from Jamie. I’ve asked him for his permission to share a section of it with you now and he has given it. This is what he wrote:

I just wrapped up watching the finale of The Newsroom a few minutes ago and found myself so affected by it and the values the show and the characters stand for. It felt particularly apt in this confusing and often disillusioning landscape we find ourselves in on so many fronts these days. I can’t help but appreciate the overlap between the values that show taps into, the values I am trying to embody as I become an adult in an increasingly volatile world, and the values deeply enshrined on Daphne and Thalia’s side of the family. Decency, good humor, intellectual curiosity, openness and general good faith. I often feel like I’m swimming upstream in a world that values these things less and less, but I am so appreciative that those values were instilled in me by many people through nature and nurture.

This is all to say that even though she wasn’t an active figure in my daily life, I will miss Daphne. I will miss knowing that she’s out there in her hot little shack in the woods, reading everything she can get her hands on, lamenting the state of the world, but always trying to learn more. We desperately need more people like Daphne these days. I’m glad we are all here to do our small part in carrying that legacy forward.”

So am I, Jamie.

____________________________________________________

Location unknown, early 1950s.

Location unknown, early 1950s.

THE OTHER SIDE

Miranda Cambanis

My Daphne, fifteen months later, I still write you mental, detailed letters, hoping to reach you, wherever you might be, having trouble with your silence except for those rare moments when you materialize out of the darkness in mysterious ways, wrapped in sounds, music and water, the very elements that defined your 97 years.

Your life was indeed the pandemonium you perceived during the last part of your journey. The catastrophic pandemic that cut you off from us in the most cruel, unyielding way, turned your indomitable spirit inward. We all hoped for a magical reversal of life, but it did not happen on time. The world plagued its ears. The music stopped. The pandemonium was silenced. You made your exit peacefully, and thankfully, I was able to hold your hand again as you gracefully transitioned towards Thalia, Subby, Tony…

It is impossible to squeeze 50 years of friendship into a brief goodbye. Grief commands its own history. Ours, was one that began over what was meant to be a quick, four-hour cup of coffee (and terrible food) at Lenoir Hall in the fall of 1970 and ended July 28, 2020, in a strange, solitary room, that none of us recognized as anything but a brief, quiet crossing. A few months back, when we could still drink our daily afternoon coffee together, you asked me once out of the blue: who do you think will greet me on the other side? I was so shocked, I dropped my full cup, fortunately, only on the floor. Who indeed? I didn’t give an answer and you didn’t ask for one. Still, the question remains and I will always wonder.

It is impossible to squeeze 50 years of friendship into a brief goodbye. Grief commands its own history.You became family swiftly and easily, as if you always belonged, joking, arguing, laughing, being irreverent, interesting, inspiring, emotional, infinite, loved. Whether traveling in Greece, or swimming the Aegean, your big love, or watching the multiple faces of the full moon during the late nights we all spent sitting on the balcony of my island home, or imitating the hoot of the white owl on top of the marble bust across the way you were sure was goddess Athena herself, your message was always loud and clear: life is here, now, today, tonight, and it is full of myths that need to be dispelled, full of magic we are all entitled to, full of joy that knows no boundaries once we open the windows of our mind and taste it.

And taste it, you did. There was no path you didn’t cross in order to see what was there, beyond all that was visible and tangible, no page unread, no thought undocumented, no storm silenced. You grew old but, like a fountain, you never ran out of ideas or words that signaled endless journeys of heart and mind.

It has to be a consolation then that we all became richer by having shared your world. Nobody can take this away from those of us who, having known you, experienced the high quality of your spirit, the spectacular colors of your language and the endless energy of your reality that will keep us going, rising from the depths of the great sadness you left with your passing.

I will close with your favorite lines of the Greek poet George Seferis whom you loved:

The life which was given to us to live, we lived it.

Pity those who are waiting with such patience

Lost in the black laurels, under the heavy planes,

And those who, solitary, speak to cisterns and wells

And are drowned within the circles of their voice.

Pity the comrade who shared in our privation and our sweat

And sunk into the sun, without a hope of enjoying our reward.

Grant us, outside of sleep, serenity.

Propelled by your example, we proclaim continuity of life, always remembering you with love.

____________________________________________________

In the kitchen of The Shack, Chapel Hill, Thanksgiving, 1946 (photo by Arthur Lavine).

In the kitchen of The Shack, Chapel Hill, Thanksgiving, 1946 (photo by Arthur Lavine).

CAVAFY’S FLAT

Elizabeth Moose

For forty-two years, Daphne Athas was an encouraging, provoking, sometimes goading, always inspiring, altogether irreplaceable force in my life. Since the spring of 1978 when I was one of fifteen eager undergraduates in her English 34W class, Daphne was to me teacher, mentor, and friend.

Daphne opened up for me the music, power, and possibilities of language. “There’s nothing quite as hopeful,” she said, “as a blank sheet of paper.” Daphne guided but never dictated. She encouraged but refused to play the role of Muse, Pythia, or Authority. She took her students seriously: she believed in our trying, messing up, trying again, finding our own ways, even “hanging ourselves” if that’s what we chose to do. When I wrote a rather overwritten story about an adolescent’s crush on her math teacher, Daphne sent me to Stendhal’s On Love. In English 47W (now known as “Gram-o-rama”), Daphne led me to Faulkner, Gertrude Stein, Anais Nin, Leonard Bernstein’s “The Unanswered Question.” Daphne affirmed my passions for Tennessee Williams and old movies.

After I graduated, and Daphne and I became friends, she opened to me other pleasures: the work of Lawrence Durrell, Marguerite Duras, Paul Bowles, Jane Bowles, Peter Weir, Elia Kazan, Turgenev, many others. She introduced me to her good friends Tony Harvey and Lee Burgess, her remarkable mother, Mrs. Mildred Spencer Athas, her beloved nephew, Dana Francis.

It’s due in great measure to Daphne Athas that I have, in the years since, explored some of that wider world.In time, Daphne and I traveled together—always on the cheap—in Greece, Turkey, Cyprus, and Egypt. In Alexandria, we tracked down the flat where C.P. Cavafy once lived. At Giza, we rode a camel and climbed deep into the interior of the Great Pyramid (it smelled like a locker room, by the way). After visiting the temple at Luxor, we munched Easter candy and drank fake beer. We hiked down the citadel at Pergamum and snorkeled off the coast of the Gallipoli Peninsula. We spent the night on Delos (supposedly forbidden) and, in Athens one night, climbed the slick marble steps of the Acropolis to gaze at the full moon. It was on our way down, mis-stepping off a low curb, that Daphne broke her leg (but that’s a story for another day!).

Back home in Chapel Hill and Durham, Daphne and those of us in the “movie group” went—like Tom Wingfield—“to the movies” almost obsessively. Afterwards, over coffee, we’d “mulch over” what we’d seen. Conversation with Daphne—at Joe Van Gogh’s, Elmo’s, the K&W, or on a beach in Greece, after a swim—was always exciting: books, plays, teaching, travel, politics, history, religion, ideas . . . all riches that Daphne shared with me.

Sixty years ago, in Concord, NC, where I spent much of my time leaning over the porch rail of the mill house I lived in, I used to dream about the wider world beyond the dogwoods and pines of my small town.

It’s due in great measure to Daphne Athas that I have, in the years since, explored some of that wider world. When I’m weary of “everyday-ness,” it’s Daphne who still reminds me that beyond the crush of grading, the pressures of campus politics, dishes to be washed, and all the other “crapola,” there is still the wild and intoxicating freedom of words and ideas, and the blue, blue sky over all.

(This remembrance was originally written in support of Daphne’s nomination for the UNC Mentor Award for Lifetime Achievement, which “acknowledges a lifetime of contributions to a broad range of teaching and learning activities, particularly mentoring beyond the classroom. It rewards those who help students develop and attain their full potential in important ways during and after their departure from campus.” Not surprisingly, Daphne won.)

____________________________________________________

Red Square, Moscow, mid 1970s.

Red Square, Moscow, mid 1970s.

VERITIES AND UNITIES

Michael Parker

I have so many things to say about Daphne that I have decided to let Daphne speak for herself. Over the 40 years of our friendship, we exchanged hundreds of letters and emails. I’ve chosen a few excerpts from those letters that represent Daphne’s sensibility, her intellect, her wit, her impeccable prose. Daphne, as you know, was no fan of hagiography, so some of my choices represent her penchant for—well, let us call it unvarnished opinion.

Postcard from London, 1995

Now, in my room at the George Hotel, in a half moon circle of a square called Cartwright Gardens, near where Leonard and Virginia had their Hogarth Press, I see in all our connection some similar universe of imagination we both responded to miraculously out of words and rhythms, and some kind of common stock of values. America is nothing now but remembered sounds—I mean since developers are the deformed progeny of the explorers—and the clues are the sounds and hammerings of the testimonies on our Puritan pages.

Letter from Greece, 1998

I went to dinner at the American Academy of Classical Studies. Talking with these mostly academics it seems more and more true they know nothing and make it all up to invent vocabularies as methods to make themselves feel better about their own disagreements. The best clues come in Homer, Aeschylus, etc. but given ignorance of context, that too ends up as a vocabulary, but one more wondrous than mere defense of method. Meanwhile, Michael, the swimming is gorgeous.

Letter from Chapel Hill, 1996

I am definitely willing to shove the idea of Art down somewhere in a pocket you can’t see too well, and consider novels, plays, etc. in terms of their “affect” on people despite my prevailing artistic notion of Art, the Verities and the Unities. I have dedicated myself to them. And just as technology has speeded up things and jittered up the plebian “receivers” (the hoi polloi that will shell out eight bucks for a movie ticket plus another for popcorn) I see that we have to consider these “receivers” or never come out into the light of day.

Letter from Chapel Hill, 1999

Some of the best friendships are those with people who love you for being a little horrible. Most people are too afraid of being steadfastly and uninhibitedly horrible. Even I have tamed my horribleness through life. Bad!

Postcard From England, 1996

I went to Cezanne exhibit (mobbed, people standing in front of each painting, copying it in sketches, I elbowed them off, because I can’t bear standing—none fell, not even me.) Terrific exhibit though, despite. Then I went to Wales. Wonderful, as I was spoiled by old friends and went squelching through castles, mad-cow fields, bluffs along the Irish sea, village sidewalks, libraries (no squelching there) tidal estuaries… The fine rain down did rain. Ate fabulous meals of boiled vegetables hardly boiled, range chickens from France, teas, tarts, but no meat pies and beer bitters. Plus, before coal fires, cognac.

Letter from Chapel Hill, 2010

I shall write you this letter because it is important to me, in terms of recognitions I have always had of you, so profound a part of my life, and perhaps the same with you.

Ours is a very deep connection, impossible to achieve unless you and I were compelled by music—both melody and harmony—which requires our synapses to be scouts of rhythm and chords to catch the meanings of those musical scores which can be written down.

Email from Chapel Hill, 2014

I have this conviction about life and death: I believe that word outlives flesh.

And now I speak to you, dear Daphne: About this conviction you were abundantly right. Daily I treasure our visits—you instructing me to drag the black leather chair as close as possible to your recliner, so that we might tell all, because you wanted to say all and hear all, but there was never time for all, and we knew that and yet never gave up on all. And Time, as you taught me to understand it, its verities and unities, will never run out, because in our minds and on your pages, the fine words down do rain.

____________________________________________________

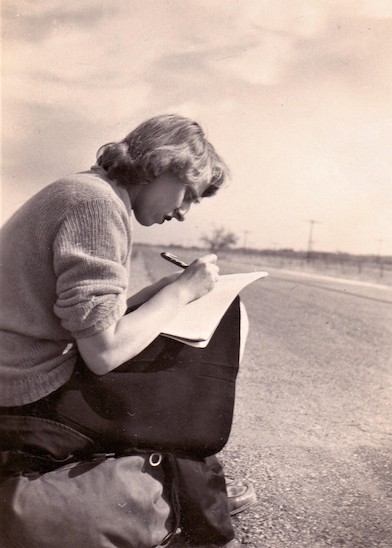

Hitchhiking to Mexico with Artie Lavine, somewhere in Texas, 1946 (photo by Arthur Lavine).

Hitchhiking to Mexico with Artie Lavine, somewhere in Texas, 1946 (photo by Arthur Lavine).

MOTHER GOOSE

Marianne Gingher

I had two mothers, a biological one and a literary one, who, born a few months apart, came of age during the Great Depression after both their fathers lost everything. My biological mother had read Daphne’s Entering Ephesus in a whoosh, as had I, after meeting her around 1974 at a Carolina Quarterly party. She was the only English department faculty member who showed up. The party was for the writer Ishmael Reed, and all the graduate students in attendance were terrified to speak with him. He sat in an armchair looking as growly as a panther, but Daphne decided he was simply bored and dared me to go sit on one arm of the chair and cheer him up with small talk. It was the first of many dares she dispensed over our long friendship, and because I never said no to a one of them, I am no longer a mouse.

For twenty years, until she stopped driving on interstates, Daphne drove from Carrboro to my house in Greensboro for Thanksgiving, toting homemade cranberry sauce in her little green bowl. Mother was there, too, and she and Daphne enjoyed animated conversations about their similar histories. My mother wasn’t book smart in the way Daphne was, but she had humor and intuition and bright-eyed curiosity that Daphne doted on. Mother instructed my heart; Daphne, less guardian than goader, waved her bedazzling wand over my mind.

Ask any of us who loved her and were mesmerized by the nearly extraterrestrial pleasures of her cosmic company—ask former students Alane Salierno Mason, Lydia Millet, Michael Parker, Mark Meares, Randall Kenan (if only we could ask him)—how she did it: her spell-binding trick of ravenous listening combined with marathon disquisitions that darted from the sublime to the ridiculous. She was a scholar of the world, disliked ignoramuses, delighted in enthusiasts, and had a soft spot for goofballs.

There will only ever be the singular and distinctive her which makes one feel all the more lucky to have known her.She left us July 28, 2020, exactly one month to the day before Randall. Ask anyone who knew and loved them both: Chapel Hill will never feel the same. We go on, of course, create new, less glamorous idols and myths, but something like the last leaf of innocence has left the tree of knowledge that the two of them planted and grew for us (and one another) to dance around, celebrating its everlasting radiance.

She called Randall “The Prince of Hillsborough.” She called me “Magnetessa” and sometime “Magnet” for short. She cared more about striving than triumph. She thought self-doubt, like shyness, was silly and self-indulgent in adults. There were far more inventive ways to be silly, like writing nonsense poems, like pontificating on everything from voles to politicians (similar animals in her view), or bouncing on grammar rules to see how much like a trampoline the English language could be. How about bursting into song, anywhere, any time, and harmonizing? She loved collaborative glee.

Often, in the middle of the crosswalk in front of the Jade Palace restaurant in Carrboro, she’d hoist her cane, do a little soft-shoe number, and belt forth a song. Of course I joined in, and we’d carry on as if we were in a musical—until some car came along. We crashed a big party once because I wanted to meet Eudora Welty and we hadn’t been invited and Daphne knew the hostess. We traveled to Greece together and sat on the beach in Kamares on the island of Sifnos eating lunch in the raggedy shade of cypress trees, our feet in the sand, drinking Mythos beer and philosophizing all afternoon before our evening swim. In Athens, she led me up what seemed to be Sisyphus’s hill to the funicular at Mount Lycabettus from which you can see all of Athens. Then, because there were no more taxis, back down the hill in the dark we trudged to our hotel—she was an inexhaustible 83 years old.

She hitchhiked across Egypt, spent summers in Greece (her father was an immigrant from Pylos), taught as a Fulbright in Tehran, was thrilled, after she smashed her bike in a traffic accident, that the EMT who scraped her off the sidewalk had read Tolstoy. They talked literature all the way to the hospital. There will only ever be the singular and distinctive her which makes one feel all the more lucky to have known her both as an elder oracle (she hated being called an oracle) and in her heyday, the 1970s and 80s, when she and Doris Betts rocked Greenlaw with their conspiratorial cackling. They gave readings together, Doris wearing dramatic scarlet and Daphne in her regal purple tunic. Iconic-looking as they strode to the podium, it seemed as if statues of Liberty and Athena had come to life. With pluck, brains, ferocious confidence, and charm, they were in the vanguard of feminist awakenings at this university. Daphne, who was 96 when she died, taught at UNC until she was 85—from 1968 until 2009.

We who loved her have stashes of photos, piles of her loquacious letters, and the elegant, funny, playfully subversive books she wrote. Future students will meet her through the course she invented as Glossolalia that we now call Gram-o-rama, a legacy course that turns the grammar lesson into performance art and celebrates the goofball in us all. She lives on, the way Edward Lear, Lewis Carroll, Dickens, Aesop, Socrates, Aristotle, and Tolstoy live on. The way the ocean lives on, the moon and stars, riddles, music, hope, absurdity, sorrow, joy, and Mother Goose.

____________________________________________________

At her typewriter, in The Shack, Chapel Hill, Thanksgiving, 1946 (photo by Arthur Lavine).

At her typewriter, in The Shack, Chapel Hill, Thanksgiving, 1946 (photo by Arthur Lavine).

STAR WARS

Elizabeth Woodman

I’m a latecomer to Daphne’s world. Randall Kenan introduced us nearly 15 years ago. He handed me a manuscript one day and said, this is a great book in need of a home. Much to my delight, Daphne agreed to have Eno publish the book, titled Chapel Hill in Plain Sight. To my surprise and delight we became instant friends—we shared stories, an addiction to Turner Classic Movies, friends, a passion for The New Yorker, publishing lunches at Elmo’s, which we called the Elaine’s of Carrboro.

My admiration grew beyond her fine writing to her entire world. She was generous, open, intensely curious. She had lots of friends: Randall, Marianne, Miranda and her beloved nephew Dana, to name a few.

I have several photos of Daphne that I look at often. One was taken at Miranda’s house of the two of them, Daphne’s head resting on Miranda’s shoulder. Miranda’s arm encircles Daphne. They smile warmly and reveal the bond and deep connection of these two women.

Daphne’s connection to friends, to Dana, to students filled every room she entered. She loved and was loved.My other favorite photo was taken one night at the Silverspot Cinema. She and her movie buddy Randall had just seen a film and walked out to find a lobby transformed into a crowded outpost of the Mos Eisley Cantina, filled with aliens and warriors lining up for a late night showing of the latest Star Wars. Darth Vader and Stormtrooper were immediately drawn to Daphne and there’s a photo of the three of them—as incongruous and hilarious as it is strangely charming. For months after she emailed it to me, Daphne brought it up in conversation, as an example of the crassness and fallowness of pop culture. What crap, she would say. I didn’t agree and we’d launch into one of those long conversation loops about culture, that were fascinating and exasperating.

I love that picture not just because of the hilarious arguments that followed or the oddity of seeing Daphne wedged into a Star Wars fantasy. I love what isn’t visible: Randall, with his phone directing them into pose, full of the mischief of dropping the most unlikely person he knew into a pop culture world that he navigated confidently. I look at that photo and hear the two of them laughing. I see their shared love of adventure and sense of fun, their deep and abiding friendship.

Daphne’s connection to friends, to Dana, to students filled every room she entered. She loved and was loved. She was not always open-minded but fully open-hearted and interested.

I was thinking about her opening essay in Chapel Hill in Plain Sight, about America emerging from the days of the Depression and war. She wrote that the nation was holding out its wings for souls to visit: “Come, it says, for I contain a hearth that defies category.” In every way I can think of Daphne defied category, and I’m grateful to have sat at her hearth for a short time.

____________________________________________________

With snorkel, location unknown, late 1950s.

With snorkel, location unknown, late 1950s.

STOLEN ORANGES

Thanassis Cambanis

Daphne took me to Mycenae when I was in first grade and she was 58, and we were both temporarily living in Athens. My father was on sabbatical and Daphne on a Fulbright, researching a novel she never completed. It was 1981. I don’t remember how it came to pass that I left for a solo trip with this mirthful family friend, but I remember that I wanted to go, and that I was also nervous to travel without my mother.

Here’s what I remember. First off Daphne instructed me to lie about my age to the bus conductor so she could pay the under-five fare for me. When we neared Argos, the bus left us on the main road, miles from the tourist area and archaeological site. As we walked, I grew hungry and tired. Daphne instructed me to scale a fence and steal oranges from a farmer’s orchard. I was terrified.

“I’ll get caught,” I said.

“You won’t!” she replied with her maniacal grin.

Hunger was persuasive. In the orchard I picked some oranges and hurried back to the fence.

“More, more!” Daphne instructed, until I had gathered as many as fit in my shirt. I threw them over the fence to Daphne who secreted them into her bag. Back on the road, we feasted on the fruits, spitting the seeds as far as we could. We stayed in a decrepit, cheap hostel with a shared bathroom. At dinnertime a large party was sharing a platter piled high with lamb, which wasn’t on the menu. Daphne sent me to ask questions—it turned out to be a wedding party—and eventually they sent platefuls of meat to our table.

That night in the unheated room I shivered beneath a single itchy wool blanket. I didn’t want to venture down the long hall by myself to the shared bathroom. Daphne encouraged me to pee off the small balcony into the street below. I remember little of the site of Mycenae itself, although it was the main objective of our trip—the place where Agamemnon lived and died, where Orestes killed his mother in the seminal act of violence that led eventually to the Ancient Greek idea of justice. Argos spawned stories, which were always Daphne’s true objective. The ruins were just a pretext for an adventure.

Daphne had merged with our family long before I was born, and she appears in my earliest memories. The trip to Mycenae was the first of many vivid moments with Daphne—moments shared with everyone who knew her. She invited accomplices to join her adventures, and cared not a bit for convention. She was curious, and as a traveler at least, fearless. She was having fun and wanted to share it. This was Daphne at her best: infectiously joyful, intellectually stimulating, generous with her mind. She challenged the ideas of others but took them seriously. She cut through bullshit and lazy thinking. She cared about ideas, stories, and her own joy. She didn’t like to waste words or money.

Everyone close to Daphne seems to have travel stories that feature cheap accommodations and rich conversation. In her seventies, she broke her leg visiting the Acropolis. She made her last trip to Greece in 2015, at the age of 91. Daphne was supremely at ease everywhere, which was a good thing since she never seemed to stop moving. She always set her sights on the place where she had put herself, not the next destination.

Daphne taught me by example to engage and be present, or else not to bother.A few weeks after Daphne’s death, I sat alone on the front deck of her poorly built shack in the woods that, like Daphne, hardly feels of this era. A family of deer rested by the rotting wooden fence, built as cheaply as possible with the bark edges thrown away at lumber yards. In my first memories of Daphne, from my childhood, she already seemed fantastically old. Her bulbous facial features telegraphed her intent with alarming elasticity. Back then in the 1970s, her little house was already crumbling. A movable bookshelf in her bedroom hid a secret passage to the attic where she kept her treasures: letters, manuscripts, extra copies of her own books.

She wanted nothing superfluous. In her study she wrote on a door placed on sawhorses, first on a typewriter, then a word processor, and eventually a Mac. She was agnostic about technology for her writing, but irritated with the false gospel of internet evangelists.

Once when I was very young she invited our family to a barbecue. She grilled some chicken on a pit she dug in the ground. We left hungry but happy, and never ate at Daphne’s again. She came to our house instead, and sang for her supper, sometimes literally.

Daphne taught me by example to engage and be present, or else not to bother. Everyone, and especially an artist, needed financial autonomy and daily discipline. She swam fifty laps every day in the university pool, tracing a comically slow path through the water with her mask and snorkel and loose stroke. She kept her body limber and strong into her nineties through the same dogged discipline with which she wrote.

She did what she wanted, and was considered monstrously egotistical by some; she rarely engaged with the pieties of others. When she wanted to dismiss some idea or person, she would hold her nose with one hand and pantomime pulling a flush toilet cord with the other, gleefully crying “Crapola!” Farts didn’t embarrass her. She wore hand-me-down t-shirts and on international trips carried a single change of clothing from country to country in a jute handbag, the type people now carry to the farmer’s market for their vegetables. She never minded the style of poverty in which she grew up, and never saw a need to change lifestyle later when she had plenty of money.

People complained about Daphne but still sought her company. Selfish, maybe, but absolutely energizing. Surrounded by examples of duty, nostalgia, and compromise, Daphne exemplified freedom. She brought the spirit of the Algonquin Round Table, as I imagined it, to Chapel Hill in the 1980s. The artist can create community anywhere, she argued by example, not just in Manhattan or interwar Paris.

Plenty of adults formed families, made compromises, volunteered in the community. Daphne offered a different template altogether: She joyously did what she wanted, damning—and ridiculing—those who got in her way. She gave freely of her time as a teacher and critic, as a labor of love, not a noble sacrifice. She didn’t linger over the hurt feelings of friends. Daphne starred in my childhood as a fairy-tale creature and remains a wonder and an exemplar for me today, when I’m a middle-aged parent.

She taught, she created, she entertained herself, and she made it look like a hoot. In her old age she didn’t moon around wondering if she should have had children or married. She relentlessly lived the present. She was equally enthused about many places where she lived and wrote: Chapel Hill, Pylos, New York City, post-war London and France, even the Shah’s Tehran. How, I asked her as a young adult chafing at North Carolina’s strictures, could she tolerate Chapel Hill after living in so many more interesting places? She rejected the premise. Only boring people, Daphne believed, get bored.

____________________________________________________

Old car with Rachel, Thalia, and Mildred, leaving Gloucester for Chapel Hill, 1938.

Old car with Rachel, Thalia, and Mildred, leaving Gloucester for Chapel Hill, 1938.

TICKS IN THE ATTIC

Courtney Mitchell

The first time I met Daphne was in the fall of 1999 in her advanced creative writing class. She opened the class with a question that could have been a question, but also could have been a trap.

“What do we think of Oprah’s book club?”

No one answered, so she looked right at me and asked, “What do you think of Oprah’s book club?”

I was from a small town, very country, and not an English major. I loved Oprah’s book club. A Barnes & Noble had just opened in Winston-Salem, the closest city to my hometown, and they had all Oprah’s selections. Kaye Gibbons had an Oprah book. Anything that got more people to read books was a good thing, I said.

I said all this while everyone, especially Daphne, stared at me.

Later that day, I was walking home from my work-study job at the hospital and saw Daphne crossing Pittsboro Street. I walked her to her car, and we had our first real conversation. She told me that when she was my age, she’d been hopping trains across Europe. She wondered why I’d never done that. I don’t know, I told her; I had a work-study job and an internship and a lot of classes. I’d pieced together an entire college education with tiny scholarships and grants for which I had to reapply each year. That world she evoked seemed closed to me. I didn’t tell her that then, but I would, eventually. Over the years, over grilled cheese sandwiches at Swensen’s and burgers at Elmo’s and spaghetti in her kitchen, I’d tell her so many things, and she’d tell me just as many and more.

What I learned in my long friendship with Daphne was that she was very highbrow to my lowbrow, a snob, but never a snob to me. She was hard on me, and a champion for me, and she loved me, and she made me feel loved.

Daphne was tough, but so tender.In the way she did for many students and friends, she wrapped me into her world. Each year, I pushed in the Scooby Doo-style bookcase that revealed the ladder to her attic and went through her papers so she could do her taxes. I ended up with ticks in my hair. She’d repay me by taking me to Elmo’s where she’d present a tiny pencil to equally divide the check. Or, she’d pop open a tiny bottle of Miller Lite for us to split on the couch. One evening before I was due to help at her house, she called my college apartment where I was, inexplicably, watching The Exorcist with friends. On the other end of the line, she made terrible growling sounds and asked: “Is the demon girl spitting pea soup yet?”

She sent me long emails when I went away to graduate school and let me use her university office for work when I came to Chapel Hill on break. When I got married, my husband became her computer support, once summoned to her home to figure out what was wrong with her computer volume. Nothing was wrong—she just couldn’t hear. She once yelled at me for scraping into the trash two spaghetti noodles that she thought I should have saved.

I was waiting for her at Elmo’s when she had her first broken leg, and they brought the telephone to the table like I was in a soap opera. She loved that detail. I found out about her second broken leg when I was sitting on my couch, staring into space two days after my father died. I went up to the hospital to sit with her and told her about my Dad. She told me how much she missed her own Dad, her “Daddy.” I was so sad, but being with her that day was so much fun. I went to hospital PT with her, and she had me cancel appointments for her like a secretary, and she loved every minute of it. I did, too.

When she was writing Chapel Hill in Plain Sight she was searching for a photo of her friend Betty Smith, and she was distressed about its disappearance. I spent hours going through boxes and photos. We got nowhere because each photo summoned a new story—about her Daddy, about a Nicaraguan princess, about Max Steele. I really wanted to give up. Daphne was grumpy and demanding. I was hungry and tired. Late that night I peeled apart two old magazines, and there it was, the photo. She banged her cane on the floor and screamed, “Oh shit! Oh goody goody!” And went right to bed.

Daphne was tough, but so tender. During the years when I was struggling to have a baby, she was concerned and interested. We went out for Chinese when I finally got pregnant, and she pulled out my chair for me. She played with my baby and sang her the songs her parents had sung to her. I returned the favor by listening deeply when she was angry about her failing body, about the world seemingly moving on without her. She never felt old to me. And she never treated me like I was young. She wasn’t a grandmotherly figure to me—she was a real friend.

I cried so much when I heard she died. I still cry every time I think about her being gone, which she would think was very silly of me, but that would be okay.

____________________________________________________

Side of the road while hitchhiking to Texas, 1946 (photo by Arthur Lavine).

Side of the road while hitchhiking to Texas, 1946 (photo by Arthur Lavine).

YOUNG ALL HER LIFE

Bland Simpson

From Entering Ephesus, the opening of chapter 5:

The town of Ephesus was called the oasis of the South. This was because of the university. It had a liberal tradition. There were only three thousand students. Everybody knew everybody else. Tuition was cheap. Many students were poor. Learning was respected. Philosophy was on everybody’s lips. It was a last outpost of Jeffersonian simplicity and Greek humanism, and it was respected throughout the state.

Stories were told about how many miles famous alumni had traveled by mule or walked barefoot to get their education. Spirit and tradition were contagious because of the perfumed leaves and lawns. The campus was centered around an old well, over which had been built a fresh white canopy with columns. Old North and old South were dormitories that had been designated state landmarks planted with plaques. Dogwood perforated spring like snow. Oftentimes classes were held outdoors. Teachers came from the North and West and spread the school’s fame. It took on a cosmopolitan air.

Ephesus had pride and its democratic ways. It was forced to defend itself each generation from accusations of being a hotbed of Communism. It put out plans for countering, erosion, unemployment, and tenant farming. Its mystique was contagious.

Juxtaposed with the Apollonian dignity of the town was an underside, frenzied, eccentric, and passionate. It existed because, as in all college towns, most of the inhabitants were young, and people were fervent in their ideas and tried to live them.

Daphne Athas was young all her life. She was fervent in her ideas. And she did not merely try to live them, she did live them.

____________________________________________________

With Randall Kenan and Alane Salierno Mason at Daphne’s 95th birthday in 2018.

With Randall Kenan and Alane Salierno Mason at Daphne’s 95th birthday in 2018.

SINGING DAPHNE

Randall Kenan

This tribute was originally published in Pembroke Magazine, No. 29 (1997). Randall died a month after Daphne, on August 28, 2020.

*

“Help me, help me

I am free.

I am what I cannot be…”

–from “Song of an American,” poem by Daphne Athas

She was Da in the Day-light, a dashing damsel, dangerous, dagger-dangling, damning daemon of dumbness; she was Ph as in Funtastic: a funny, funky, Phaedra of the faith, fighting the Philistines, fleeing fledgling foolishness; she was Ne as Night began, nimble, neat gnashing nay-sayers, knitting nettles for the nabobs of negativism—Da-ph-ne, a diphthong of phonemes in the nether; a diaphanous, phantastic, neology: Daphne. Daphne. Daphne. Daphne.

(I cannot resist the temptation of playing further with Daphne Athas’s name—a wordsmith who abhors the bothersome trend of turning perfectly good nouns into verbs or perfectly good verbs into nouns—as in “authoring” or “stoppage” or the jerry-rigging of nouns or verbs into awkward adjectives. But I can’t help but wonder at the possibilities of Athasize, Daphicate, Athasify, Daphnesque, Athasian, Daphniation, Athasmentation, Daph…)

As an undergraduate at Chapel Hill, I certainly knew of this woman before I knew her: saw her pedaling her vintage bicycle down Franklin Street or across the campus toward Greenlaw; heard rumors and testimonials from her former students, still wide-eyed and bewitched; noted her laughter down those tell-tale halls of English literature, a sonic blast of joie de vivre; recognized her knowing, wise, gentle, mischievous smile and that platinum/plutonium glint in her eye—but it was not until English 47W—a writing course in stylistics—that I came to begin to reckon with this latter-day Hypatia of Chapel Hill, a high priestess in the Alexandrian Faith of the Word.

English 47W, as Daphne chose to run it for years and years, so became some-what controversial within certain Old-Guard quarters, primarily because Daphne shunned the notion that learning should be perforce dry-as-dust, austere, proper, remote, apart—a Holy Fetish of the Cardinals of the Church of English. In her hands, language revisited its funkiest roots, became juicy and ribald, dynamic and potent; once again the language for bodily fluids and amour fou, for the tongues of the saints and prostitutes: 47W was fun. Serious fun.

As for me, I learned—and came to respect—the English language more than I had to that date. Nuggets from such disparate sources as Jacob Jacobson, H.L. Mencken, Edward Lear, Lewis Carroll, Sid Caesar, William Shakespeare, Milton Berle, Geoffrey Chaucer, S.J. Perlman, Virginia Woolf, Ludwig van Beethoven, Noam Chomsky, Groucho Marx, J.S. Bach, William Faulkner, and the authors of the Old Testament, were deconstructed, reconstructed and then not merely studied, but made into the clay from which they were originally formed.

And we students were then bid to play with them, play around, play up, play down, play over, play under, play light, play hard with this language, these rhetorical devices of the sentence, these denotations and connotations of the word, these resonances of the sound. Music and meaning. Look at the language Beethoven chooses for “Ode to Joy.” Hear the music in “Jabberwocky.” Turn the words of Hemingway into gibberish and with what are you left? The tones and structures of Genesis! There is sense in “Non-sense,” Daphne taught us, and glorious non-sense in “Sense.” And, perhaps if you’re lucky, by putting non-sense and sense together, you may get that elusive Holy Grail of meaning; perhaps, you might find, on some alluvial, some damp, swampy, oozing and primordial plain, some ur-truth about this thing that Anthony Burgess has called A Mouthful of Air: Language.

In the end, our work begat a show about language, equal parts education, edification and entertainment: word fugues and word symphonies, playlets and monologues, language turned on its head, parodied, pushed, stretched and shattered. For me, the descendant of men and women who were forced to take up English, and who, through cleverness and necessity, created new forms from the language of Shakespeare and King James (the Bible) and of lost Africa (Hausa, Ibo, Yoruba, etc.), this study with Daphne opened my eyes to new possibilities, to old fundamental truths—I came to see that I could spend a lifetime playing with language and would only begin to get to the center of its power. Daphne, in short, made me a Sorcerer’s Apprentice of the Word.

Of Daphne, I remember her powerful mix of down right bluntness when she felt she encountered something false or implausible, both situational or emotional—and her effusiveness when she found something praiseworthy and real.My next formal encounter with Daphne Athas was in the benighted English 99—the honors writing seminar at Chapel Hill—which, that semester, Daphne team-taught with the writer Doris Betts. I fondly remember Daphne and Doris sitting in their respective places among the dozen or so students, students gathered in a miasma of youthful ego, trepidation, energy, and hope. Were we dreaming of Joyce and Styron, Wolfe and Faulkner? Were our eagerness and ambition palpable as honey on dry bread? Daphne and Doris have and had different styles in teaching and critiquing students, but they share a complimentary and complementary sense of irony and wry wit.

Of Daphne, I remember her powerful mix of down right bluntness when she felt she encountered something false or implausible, both situational or emotional—and her effusiveness when she found something praiseworthy and real. Her eye was always on the look-out for the distinguished and the unusual lie that told the truth, often its way of telling being its own veracity. Daphne seemed to possess a homing device for bullshit, and an equally diligent one for the honest and the true and the human.

*

Upon leaving Chapel Hill, I was laden-heavy with gifts, and not a few were the gifts of having worked with Daphne Athas. She gave as gifts especially Gertrude Stein and Vladimir Nabokov. (Theretofore Stein made absolutely no sense to me, but through Daphne’s passionate interdiction, Four Saints in Three Acts became frightfully clear; her exegesis of Nabokov’s short story, “Signs and Symbols” truly altered my concept of what fiction could do to human perception.) And so much else was her bequest, much of which was simply Daphne being herself.

As one sees Daphne—Daphne traveling, Daphne teaching, Daphne going to the movies, Daphne seeing and indulging and enjoying her friends, Daphne writing, Daphne reading, always, always, always reading—one sees a whole person; one sees a woman defying stereotypes, defying age, defying the definitions of ennui and atrophy and entropy that are supposed to overtake her; one sees, in Daphne Athas, the blueprint and the working model for a life well-lived, and it is difficult to spend any time with Daphne, or talk to Daphne, without being affected by this wonderful zest, this virus for good living—not the Good Living of money and laziness and ease, but the good living of an active and voracious mind, the desire to see and to hear and to taste and to smell and to touch the world, to learn and to grow and grow.

For me, this was Daphne’s legacy—the sum total of which, over the years, I would see as a shaman’s pouch: seemingly small and finite on the outside, but inwardly containing worlds without end.

But thankfully my apprenticeship continued and (perhaps I flatter myself in thinking) still continues with Daphne Athas. Each year, after I left for New York, I would return to Chapel Hill and meet with Daphne always at the Looking Glass Cafe. And why the Looking Glass? A tribute to little Alice and Lewis Carroll? We didn’t say. Perhaps the gentle atmosphere, perhaps, and I suspect the real reason, after our first conversation there was that the memory remained so strong and true that we wanted to continue that rare, good meeting and so it became “our place.” In 1994, when I returned to the Triangle to teach for two semesters, we then would regularly meet at Elmo’s Diner in Carrboro and there the intensity and fidelity of our conversations soared even higher, and I continued to learn.

Mind you, a conversation with Daphne Athas can be an experience in and of itself. The phenomenology and philology of her speech alone are both arresting and instructive. Daphne has been described as speaking in stream-of-consciousness. A typical conversation with Daphne would begin with a discussion of Tolstoy’s characterization, which would lead to a discussion of Dostoyevsky’s characterization, which would lead to a discussion of Haitian mysticism, which would lead to a discussion on her nephew in Oakland, which would lead to a discussion of California, which would lead to a discussion of Athens, which would lead to a discussion of London during the War, which would lead to a discussion of her friend and fellow writer and colleague Max Steele, which would lead to a discussion of Frank Porter Graham, which would lead to a discussion of Senator Jesse Helms, which would lead to a discussion of government, politics, and the military, which would lead to a discussion of Hillary Clinton, which would lead to a discussion of Margaret Thatcher, which would lead to a discussion of Vivien Leigh, which would lead to a discussion of Thackery, which would lead to a discussion of Dickens, which would lead to a discussion of Dostoyevsky, which would lead us back precisely, logically, as if the topic had never been left—to her original point about Tolstoy’s omniscience and humanity and sureness. Her conversation is a brilliant exercise of fluidity and intellect, woven right before the eyes in a language rich and punning and always intelligent and be-jeweled with insights.

I am pleased that Daphne often refers to our successive conversations as a “continuing conversation.” Once we had a discussion on one of my own stories, “The Far; or, A Body in Motion,” a story written from the point of view of Booker T. Washington, a story which disturbed her in regard to my playing fast and loose with historical figures so close to our present—a conversation that went on for almost two years, a conversation carried on over dinner, over the phone, through cards and letters. And though I am not to this day certain if each one of us came to change the other’s mind, radically, about this issue, I for one am certain that, because of Daphne, my understanding of the matter is deeper and broader and better considered.

To me that is what Daphne does, what Daphne is, at once a lightning rod and the lightning. Like Gertrude Stein before her, I can see Daphne saying: “One cannot come back too often to the question what is knowledge and to the answer knowledge is what one knows.” Or, “Supposing no one asked a question, what would be the answer?” Or, “… I just tell you and though I don’t sound like it I’ve got plenty of sense, there ain’t any answer, there ain’t going to be any answer, there never has been any answer, that’s the answer.”

*

By birth and by nature and by circumstances, I have always seen myself as an iconoclast and an outsider, and perhaps because I sensed something of the like in Daphne Athas (Northern-born and partially reared, coming young to the South; of a strong Greek heritage in a bastion of Southern hegemony), that I felt instantly akin to her. In her essay, “Why There Are No Southern Writers,” a decidedly iconoclastic take on the prevailing need to lump Southern writers into one Big Regional Tradition, and in her novels and in person, one sees Daphne Athas always as a figure pushing against conformity, knocking on the doors of right reasoning, celebrating the Other, not simply because of its “Otherness” but because of its inherent value (if value is there) often overlooked, ignored, discredited.

Thus Daphne’s theories about language, thus Daphne’s most lasting gift to me, and to so many others. For Daphne believes, like truth in the Old Testament, that Language can make you Free. In her unpublished magnum opus on language she presciently, and in detail, lays out what Toni Morrison so forcefully put forth in her 1993 Nobel Lecture: That language can enslave us, cut off our tongues, imprison us, stultify us, kill us. Yet fresh new language, the language both of the gutter and of the soul, can lift us from the muck and mire of television and advertising and governmentese and legalese and institutional bone-and-ash talk and military claptrap—from the demonic power of race-baiting and the sinister power to degrade women. Therefore, the sense and the non-sense of Daphne Athas have their roots solidly sunk into the good earth, and are based in—though she would scoff at the word (so ill-used, so misused, so robbed of meaning)—a morality. Thus the meaning. Thus Daphne. Or, to paraphrase Robert Browning: “Daphne Athas means and she means good.”

As a continuing and bless’d student of Daphne Athas, I continue to sing her praises, in sense and non-sense; I continue to hope to learn how she robs bad language from the ignorant and spins it into fine gold, how she takes the most poisonous of phrases and makes them edible, how she scoops up dust-laden and brittle sentences and makes them flow—how she sets words on fire.

Surely Daphne Athas is a sorceress of the word.

May we all learn her witchcraft of wordcraft—and of life.