Jumping off Wallace Stevens’s classic poem, “13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” 13 Ways of Looking asks authors to show the visual inspirations for their latest projects, with accompanying background on how these images directly or indirectly influenced their book. First in the series is Samantha Hunt, author of the novel Mr. Splitfoot, the short story collection The Dark Dark, and, most recently, The Unwritten Book.

–Rob Spillman

*

The Unwritten Book is my first work of nonfiction. It explores the broadest sense of ghosts. Chapters collect the ways we get haunted: dead people, the forest, family, addiction, the towering library of all the books we’ll never have time to read or write.

Nestled within is a ghost book, an incomplete manuscript about people who can fly without wings, written by my father and found in his desk just days after he died. I read his unwritten book as a way to live closer to the dead, to ferment fear into wonder. I read his book as a detective collecting evidence, and, like the dead, clues are everywhere, in birdsong, pop music, ancient documents, loves and hatreds, and in the archive of images floating all around me, including these that inspired my book:

When I was young I dreamt about a small door. Crouching through the door, I passed into a series of small scarlet, velvety rooms, like a birth canal in reverse. I knew the tunnel contained mystery but I never pressed through the tunnel all the way, rather, I sat in the small passage, content in the unknown, happy to be hidden.

The first time I saw Mr. Morgan’s blood red library I was reminded of the dream tunnel and suddenly thought, This is where that tunnel leads, to a library, or maybe a used bookstore. It left me with a peaceful vision of death. I am a slow reader, so death as a place where I’ll finally get some reading done, is heaven indeed.

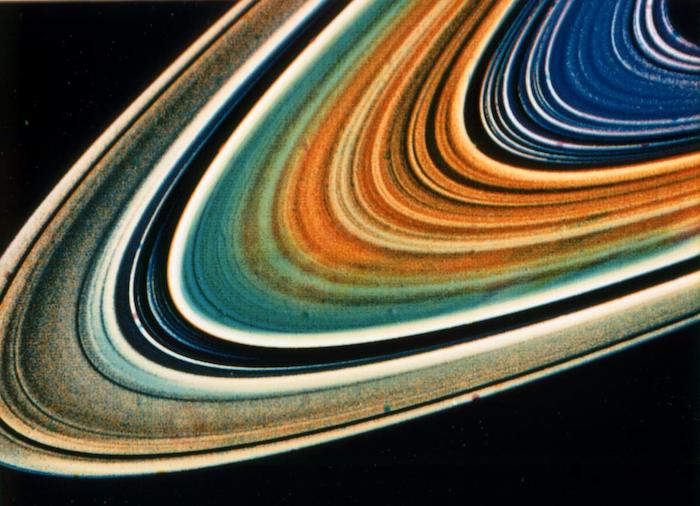

The rings of Saturn consist of individual ice crystals and meteorite particles held in a circular orbit. And look how beautiful they are. The rings of Saturn share a structure with the way we think, the way I write, floating from part to part, cell to cell, ice crystal to ice crystal across the synapse in order to make a whole. Multiple moments from history can rest near or on top of one another, procreating, generating, electrifying the in-between. For example, the New York Public Library has been a potters’ field, a reservoir, a battleground, a forest.

When I was a girl I was given a set of tiny green lemonade glasses for my dollhouse. My attraction to these miniatures was so strong that I swallowed a handful of the beautiful glasses. My grandma Norma made me these three little hats. I didn’t swallow them. The miniature is having a large moment. Tiny is powerful. Tiny has always been powerful. Women, children. A virus, a raindrop, a word. The local is stronger than the global.

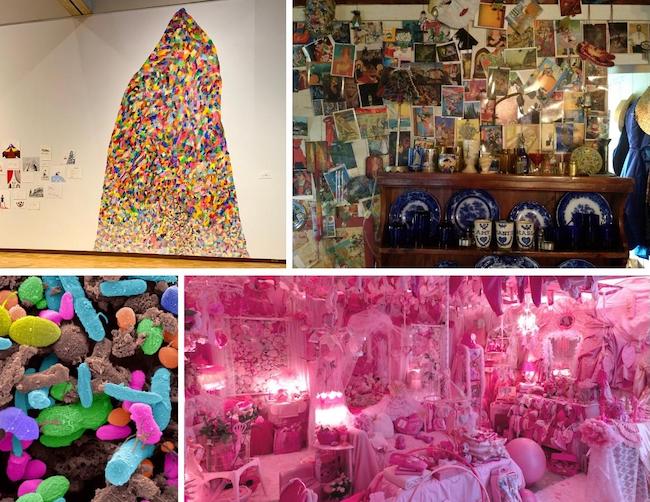

Collecting the small differents, and differences too. My mom’s house resembles a Nick Cave Soundsuit, Tyree Guyton’s The Heidelberg Project, Makeal Flammini’s 13-foot-tall mountain of colors made out of crayon in Milwaukee, and the pink installations of Portia Munson. My mom’s house is a beautiful gut biome, though she would shiver to hear me call it that.

I love images of gut biomes, like this beautiful one taken of human feces by Martin Oeggerli for National Geographic . My mom keeps a drawerful of nail polishes beside a toy turtle beside a pink pillow beside an expired jar of my dad’s cancer drugs beside a golden statuette of the Virgin, beside a wall of art books.

Everywhere is something interesting and I make it make sense. I tell her, “You can’t hold on to every beautiful thing.” But watching her sort through a pile of old magazines is like watching an Arctic hunter carving up a seal. There’s no part of the beast without a purpose; nothing goes to waste under my mother’s attentions.

Like her, I also keep many objects left behind by my dead. I inherited my neighbor’s end table when she died. I am sitting at it to write, right now. I found a disposable camera in its drawer. The camera was old, 80s design. I sent it out for processing, hoping to find my neighbor or some other deep past in the film. Gillian Welch sings about dreaming a highway back to people and times that are lost. She describes the roads we sometimes walk back to the dead. Time had really turned up the violet, blue, and green in my neighbor’s film. Every image was of her peach tree laden with ripe fruit, some old summer saturated by unreal colors, a glorious fruiting in the film’s decay.

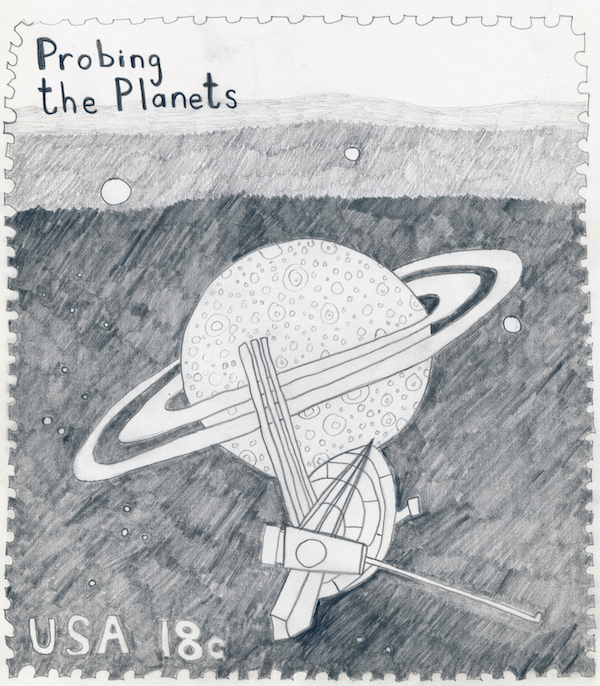

Years ago, I sketched some of the more beautiful stamps from my grandma’s enormous collection, albums she’d compiled from age 5 to 101, when her work was finally complete. After my grandma died, I woke one night with heaviness and dread. I missed her. I blinked in the darkness. In a matter of moments, I heard small footsteps coming down the hall to my room. One of my daughters climbed into bed beside me. There are multiple reasons why this might have happened, but I believe what I can feel. I am affected by fictions in very real ways. The novels I inhaled as a girl, stress, the conversations of birds. I chose to believe that my granny sent my daughter to comfort me. That reason feels best, most right, most kind. It is the finest story I can tell myself. I fell back asleep with her warm body beside mine.

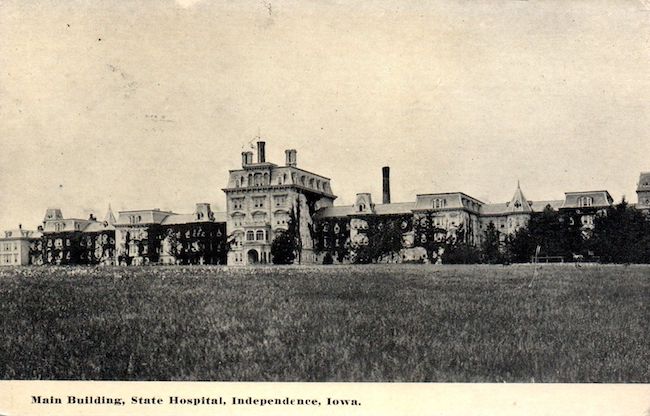

In 1891 my great, great aunt Ella was institutionalized at the Independence State Hospital because she boarded a moving freight train bound for Council Bluffs. She was 21 years old. Her family brought her to the asylum at Independence. Her admission interview asks “On what subject or in what way is derangement now manifested?” And the answer: “She wants to travel and will run away when not constantly watched.”

Ella died at the asylum five weeks later. Her death certificate says brain derangement. I suspect something far darker and more deranged, something to do with the way the world fears female bodies because at our centers we contain an emptiness, a place of unimaginable possibility, the void we’ve all come from.

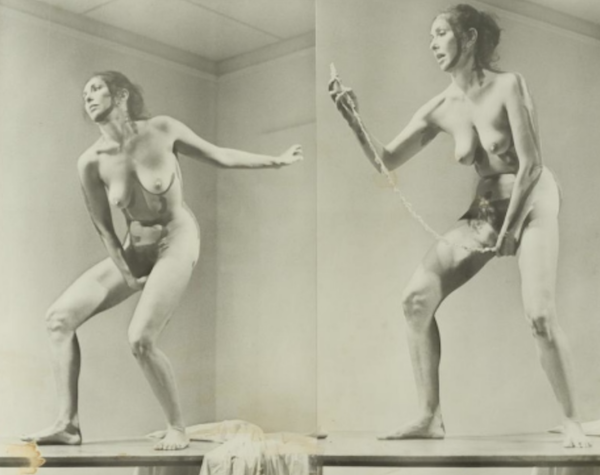

In As I Lay Dying , William Faulkner’s character Addie says, “The shape of my body where I used to be a virgin is in the shape of a .” Is emptiness ever actually empty or simply mysterious? In Haruki Murakami’s story “UFO in Kushiro” a character asks, “What’s the something inside that box I brought up here?” and receives a terrifying answer, “That box contains the something that was inside you. You didn’t know that when you carried it here and gave it to Keiko with your own hands. Now you’ll never get it back.” A womb, a tomb, and Carolee Schneemann’s glorious Interior Scroll from 1975, there to correct the record, erase the fear of female holes. A naked Schneemann pulls a scroll of text from her vagina and begins to read the truth aloud.

When I was breastfeeding my twins, one kid per boob, I’d rest a book between their heads and consider the tremendous symmetry of bodies. It frustrated me that unlike my boobs, my eyes had to work together. I wanted to read two books at the same time. One eye on the left, one on the right. What greed. What hunger for books. I couldn’t do it. But maybe you can.

The unwritten book my dad started writing and never finished, is about an anonymous society of people who can fly without wings. My dad was a member of a very large, probably the largest anonymous society, A.A. He also had flying dreams his whole life. He also had a scar on his back where they removed part of his lungs. That scar could be read as the place where he lost his wings. His partial novel was very close to his real life, but also different. In The Unwritten Book I printed his unfinished novel alongside my own commentary on his work. My text is on the left hand page, his story is on the right. Tandem reading, if you can.

In a profile by Hilton Als, playwright Suzan-Lori Parks says of her characters’ speech, “It’s, you know, blah-blah-blah doin diddly-dip-da-drop. It’s just sound. It’s the sound of the dead, and the dead don’t make living sounds.”

In Flying Lotus’s “Coronus, the Terminator” video, directed by Young Replicant, a man lies dying in bed, surrounded by family. They wash his body. They lay their hands on him. As the man slips away from life, a car arrives, human-like shadows are cast on the laundry line. The beat begins and the dead man walks downstairs. In his living room he finds three strangers assembled. They are dusted in ghostly white powders. They begin to move in a way that is irresistible. The beat hypnotic. Its slowness speaks of confidence, certainty. The man, recognizing why the strangers have come, flees. He runs through the city, trying to escape death.

“Coronus, the Terminator” is from Flying Lotus’s opus You’re Dead! From the intensity I feel in that song and its images, I began to build a device in my head. I call it the Mourning Machine. It doesn’t work yet. That’s not a problem. I’m still not even entirely clear what the machine looks like, but I know it is dark inside, a place for transformation, a place where skin is all pores, all holes.

The Mourning Machine is not made out of new things but contains a junkyard of devices other people thought too old to function anymore. It contains forgotten engines and tools that have been liberated from serving capitalism. There will be old train cars for Ella and my dad, old record players that spin not only at 33, 45, and 78 but other tempos as of yet unheard, 12, 9, -4, 111.

The Mourning Machine involves being drenched in sound, words, images and songs that take our breath, translate other frequencies to our human ears, sounds that stop our hearts just enough so that we, the living, can approach a place where it might be possible to speak with, sing with our dead, even if that singing sounds a lot like silence.