Remembering Alice Wong: Writer, Advocate, Friend

Steven W. Thrasher on Meeting and Collaborating with the Outspoken Founder of the Disability Visibility Project

Though we were in frequent conversation for a decade, I only got to meet my friend Alice Wong in person just once.

And when I did, I was a bundle of nerves—and that was before she cussed me out within a minute of our first embrace.

It was October 2022, and I had traveled to Alice’s home in San Francisco. By this time, Alice could no longer speak, as she’d undergone a tracheostomy a few months prior. I felt honored, and a bit intimidated, to be invited into her space, and to see a sliver of the human and technological care it took for the author of Year of the Tiger and the founder of the Disability Visibility Project to remain in the world with us. She’d recently, and just barely, survived a harrowing hospital stay during a Covid surge (which had taken away her capacity to speak).

I was shown to a patio and waited for her to roll out. When she came, she was all smiles and we hugged gingerly but warmly.

But then her aide brought out a plate of cookies and set them in front of me.

I didn’t want to eat in front of someone who couldn’t eat!

At first, I tried to ask, Shouldn’t I stay masked? But Alice assured me we were outside and sitting far enough apart.

Then, I tried to self-deprecatingly say I was too fat to eat sweets, and I really needed to lose weight.

Alice wasn’t having it, and typed into her speech machine, “EAT THE FUCKING COOKIES!!!!”

This made me relax and laugh, as Alice had been making me do for years.

It was, as someone responding to this story when I told it over the weekend, a typical example of the “Alice we knew and loved.” She wanted everyone to feel good and sexy and happy in their bodies—not just despite their differing aspects of ability, disability, race, gender, fatness, thinness, and size, but because of them. Alice had unlearned enough internalized ableism that she was not going to let me succumb to my own internalized fatphobia, my internalized homophobia (by way of feeling, in San Francisco in particular, that I wasn’t skinny enough to be gay) nor to my fear of offending someone who couldn’t eat. Alice took joy in seeing others eat. Indeed, a year later—in the midst of a deep depression, when our hearts were both breaking over the genocide in Gaza and I was on the cusp of professional ruin—Alice and her sister baked and mailed me Christmas cookies.

Alice helped decolonize disability communities of their (often) white-centered nature and acted as a bridge between so many interdependent related struggles.

That’s the kind of care Alice gave: she wanted to help the people she loved experience maximum pleasure—even pleasure she herself could not experience. Just giving someone else such pleasure gave Alice pleasure.

And that, amongst many lessons my friend taught me over a decade of conversation, was maybe the most important lesson of all: that giving pleasure, joy, affirmation and care to people you only meet once—or who you might never meet all, such as all the Palestinians Alice cared for these last two years—is the very meaning of love.

*

Alice embodied the difference between an intellectual and an academic. She was as excited and sophisticated about philosophy as anyone I’ve ever met, while being totally unencumbered by the petty bullshit of academia. She did not gatekeep knowledge; she shared it with the generosity and glee of a neighbor passing out full-sized candy bars on Halloween.

I first connected with Alice via Twitter around 2014, as I was reporting on the stigma of HIV criminalization for BuzzFeed, covering the Black Lives Matter movement for the Guardian, and starting my PhD in American Studies. Alice quickly became my intellectual playmate in the world of ideas, especially in terms of discussing the overlap between HIV/AIDS, queerness, race and disability.

She had recently begun the “Disability Visibility” project, which was dedicated to “creating, sharing, and amplifying disability media and culture.” I was thrilled when she started following me. As the writer Claire Willet put it, Alice was “the gold standard of what Twitter was when it was great—how you could just find these brilliant, remarkable people with the kind of voices that rarely get platformed or taken seriously, and hear about their lives in their own words without intruding on them or demanding emotional labor.”

Gold standard, indeed. I quickly learned that online and off, Alice embodied the best of community organizing. For starters, there is no singular “disability community.” The accommodation needs, experiences, and cultures of people with different abilities regarding sight, hearing, mobility, pain, cognition, and emotion are extremely varied; multiply that by differences of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, income, and class, and it’s hard to hold such a coalition together.

And yet, if not exactly singularly cohesive, Alice helped make Disability Visibility a community where writers with all kinds of disabilities were welcomed and interacted in productive ways. It also helped “ableds” understand that disability is not merely a source of pain or trauma but a spring of creativity, brilliance and joy.

Alice also did something even more profound: she helped decolonize disability communities of their (often) white-centered nature and acted as a bridge between so many interdependent related struggles. As she’d write years later about Palestine, though I knew many years ago she applied the same principles to Black lives and LGBTQ rights, “Solidarity isn’t transactional or conditional,” and “disabled people shouldn’t care” about current events just

because they can relate to what is happening. Cross-movement solidarity is another disability justice principle that I deeply believe in. We need to build relationships and show up for other movements because that’s a way to build power and it’s just the right thing to do.

That is, I believe, how Alice and I first started talking: when data clearly showed that per capita, police not only shot Black men more than any other racial demographic in the US, but that about half of all people killed by American police had a disability. We built cross-movement solidarity between us, and learned from each other.

From there, we were off and talking about everything: the links between labor rights and climate justice, Star Trek (mostly but not exclusively The Next Generation), critical race theory, new works in disability studies (by Sue Schwek, Sami Schalk, Eli Claire and Sunaura Taylor), our frustrations with the Democrats, our crushes on hot guys (I hope no one finds our messages about Diego Luna on Andor), our shared love of The Naked Gun and the New York Times pitchbot account (which eulogized Alice this weekend, with a parody-Maureen Dowd column tilted “To Alice Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything”).

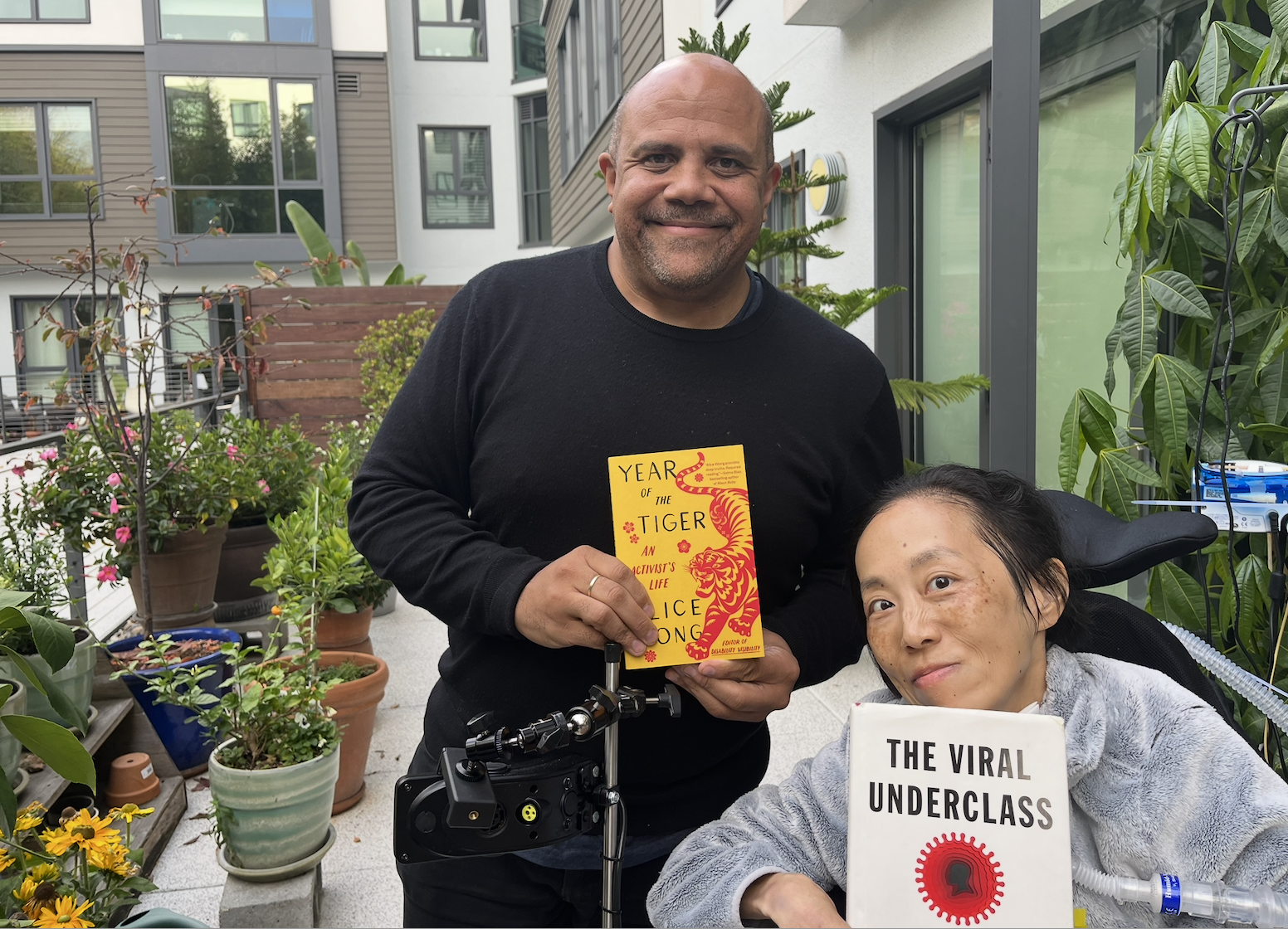

Steven Thrasher and Alice Wong, October 21, 2022 (courtesy Steven Thrasher).

Steven Thrasher and Alice Wong, October 21, 2022 (courtesy Steven Thrasher).

We talked shop about journalism, and we talked endlessly about the ethics of journalism. Alice is often referred to as an activist, and sometimes as a writer or an author. But she was also a journalist, and a damned good one at that. The Disability Visibility Project is one of the great American journalism initiatives of the last few decades. She was a journalist who wrote like a poet, challenged power, pushed readers to interrogate subjectivities, explored root problems, and carefully reported new information of value to the reading public. She was also an excellent editor, helping writers from all kinds of backgrounds (rarely heard from in mainstream media) to report about their experiences of disability.

Also, Alice’s last social media post, written just a week ago, was about being “heartbroken” that her column at Teen Vogue had been kicked to the curb, along with the entire Teen Vogue politics staff. (And there’s no journalistic bona fide as authentic as getting shitcanned!)

In addition to her beautifully written memoir Year of the Tiger and the three volumes of writing she edited (Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century; Disability Intimacy: Essays on Love, Care, and Desire; and Resistance and Hope: Essays by Disabled People), I taught many of Alice’s essays in my journalism classes. These included “Constant Cravings” in Eater, which Alice wrote after she could no longer eat, and which includes a description of peaches so sensual that would make the filmmakers of Call Me By Your Name blush; “Disability, pleasure and ageing: The pleasure principle” in Archer magazine, one of the most intimate essays on masturbation you will ever read; and “I’m disabled and need a ventilator to live. Am I expendable during this pandemic?” published at the onset of Covid in Vox.

Alice had a wicked, bawdy, and often extremely horny sense of humor.

This last essay is what led me to interview Alice for my book The Viral Underclass. “My life is rich. It is not a failure” she told me in that interview defiantly, despite all the ableism that was meant to make her feel like her life did not matter. The conversation was so profound that the first page of my book begins with Alice’s declaration that “the world is one big petri dish” as an epigraph.

Writing can be lonely work, and Alice was one of a handful of authors with whom I could talk about the opaque, frustratingly mysterious, ego-checking, self-esteem destroying aspects of book publishing.

But we also gabbed about the literary, sublime aspects of the writing life—including about matters of life and death.

When she turned 50, Alice wrote in Time that living with muscular dystrophy meant that

Death remains my intimate shadow partner. It has been with me since birth, always hovering close by. I understand one day we will finally waltz together into the ether. I hope when that time comes, I die with the satisfaction of a life well-lived, unapologetic, joyful, and full of love.

But before her tracheostomy, in one of the last times I had heard her voice on the phone, Alice had already told me she felt like she was “racing against clock” to get articles published and her books done.

There is an inherent connection between different communities for whom death has been a “shadow partner.” From 1981 until drugs became available 15 to 25 years later (depending on where you happened to be born on the globe) queer culture was forged in the shadow of AIDS. Similarly, Palestinian culture has been forged in the shadow of genocidal death not just for the last two years, but since 1948. The same is true for Black people and disabled people.

And yet, for those able like Alice to dance with the Grim Reaper, we don’t have to wait to waltz into the ether. With death and each other as partners, we are able to dance, and live, and love right here and now.

*

Alice had a wicked, bawdy, and often extremely horny sense of humor, as evidenced by her vocal performance as herself on the Netflix-Big Mouth spinoff cartoon, Human Resources. When we met in San Francisco and took a picture together showcasing each other’s books, we captioned our meeting “a collaboration too hot for Only Fans.” She had a mouth like a sailor, whether that was while being interviewed by me for my book (“ I feel like for so many marginalized communities, we are basically the oracles? You know, we’re the ones who see shit before it happens”) or in her own obit, which she wrote to be posted after her death: “Don’t let the bastards grind you down. I love you all.”

Fiery final words from a woman who was often angry—angry at ableism, angry at the denialism surrounding one million Covid deaths in the US, angry at white supremacy. We often discussed how as a disabled, Asian American woman, she was expected to be meek and demure and just grateful for whatever crumbs she could get… and she wasn’t fucking having it. Her idea for liberation was that marginalized people could fully embrace the entire spectrum of being human—including being mad as hell at injustice.

Alice was terrified thinking about how extra-frightening the bombings must be for people who lived with deafness, blindness, Down syndrome or conditions which required careful medical care in Gaza.

Alice was angry (as was I) at the way Elon Musk ruined Twitter, which had once been such a vibrant community. We DM’d each other many times a day for years, something we could never quite make work as frequently via BlueSky or text messages for some reason. She also could get understandably mad when people wrote to her expecting fast responses and free labor from a single “crip” living with muscular dystrophy on a fixed income in San Francisco.

But if these things made her upset, the genocide in Gaza made her furious. (Of course, Alice’s obituary in the New York Times obituary omits any mention of her activism on Palestine; for a much better obituary, read the one by Miles W. Griffis in The Sick Times.)

During the first week of the Gaza genocide, Alice and I were DMing constantly. We were both despondent. She was terrified thinking about how extra-frightening the bombings must be for people who lived with deafness, blindness, Down syndrome or conditions which required careful medical care in Gaza. And she predicted—correctly—that the genocide would make even more disability.

“All I can do,” Alice told me in October 2023, “is add alt-text to images.” She felt helpless.

But she didn’t stay helpless. Alice, Jane Shi and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha started “Crips for eSims for Gaza.” With a total blockade on sending goods and a near blockade on sending money, the three disabled people came up with a novel helpful hack: to put money on Palestinian’s eSims, so that they could keep using their mobile phones.

To date, unpaid and with zero institutional support, the three “crips” have raised $3,129,604 dollars and counting from more than 56,000 donors. Alice provided life-saving care to people she will never meet (in this plane, anyway).

But if Alice’s stalwart support of Palestine evaded any interest from the New York Times, it was of extreme interest from Zionists when Alice was named a John D. and Catherine T. 2024 Mac Arthur “genius” Fellow.

Alice announcing she had won a MacArthur should have been one of the happiest events of her life. Disabled activists had lobbied for her to win for years, as they wanted her to have the space to do her public work from her home in her community, as well as to have the money to avoid the financial pressure to be institutionalized.

But when her award was announced, she and Princeton Professor Ruha Benjamin—another 2024 MacArthur fellow and woman of color who’s been outspoken on Palestine and subsequently punished—were bombarded with threats. The Zionist PR-war machine came down on their heads.

Alice was dismayed and depressed. When the death threats came, she told me that she feared for her life. When Zionists announced they were going to get her MacArthur award rescinded, Alice feared they would be successful in taking away this financial lifeline. The Zionists did not succeed in that, but they did seem to pressure the foundation enough to take down Alice’s own words on her work and a link to her support for Palestine.

When Alice asked the foundation for help with the death threats, she told me she felt abandoned, unsupported and left to swing in the wind. And when she complained about her statement coming down, she told me she was angry that all the foundation did was to take down everyone else’s links and statements, too.

Still, as she did when she lost her ability to vocalize (and you must listen to her technology-aided May 2023 KQED essay “I Still Have a Voice”), Alice did not stop speaking out on Palestine. When I was suspended from teaching over Palestine, she was one of my first and loudest supporters.

Last year, at this website, Alice and I wrote “A Letter Supporting Six Honorable Journalists in Northern Gaza,” which 240 other journalists co-signed. We penned it after Israel threatened six journalists’ lives. Tragically, two of the six—Hossam Shabat and Anas al-Sharif—have since been assassinated and are waiting to greet Alice on the other side. Also, at least one of them, Ismael Abu Omar, was severely disabled when his leg was blown off.

Alice remained curious, steadfast and enthusiastic about the Palestinian people until she died. Her final message to me was after she saw me interview the UN Special Rapporteur to Palestine about HIV in Gaza a couple weeks ago: “Hi Steve!!! I saw your post about the question you asked Francesca Albanese. How cool! I wish she could come to SF and give a talk.”

With less than a month to go until she and death would “finally waltz together into the ether,” Alice was still enthusiastic thinking about a free Palestine with a sense of wonder.

*

Alice (this part is to her, though the rest of you are welcome to eavesdrop): We both talked about how as kids, we never dreamed we’d grow up to be published authors at all, let alone book buddies whose books wound up on lists together.

But as an adult, when the possibility of being an author seemed within grasp, I dreamed of having exactly the kind of friendship with another author as the one I was so blessed to share with you.

And now, dear friend, you are gone? How could you leave me? How could you leave all of us, who need you so much?

Or, are you gone?

Two texts remind me of your ongoing presence in my life. One is the poem at the end of a movie you and I had complicated feelings about from a disability perspective, Guillermo del Toro’s The Shape of Water. But the words spoken in its climax capture how close I feel to you now that you’ve crossed over:

Unable to perceive the shape of You,

I find You all around me.

Your presence fills my eyes with Your love,

it humbles my heart,

for you are everywhere.

And the other is a text by you. Until we meet again some day in the cosmos, I promise you, dear friend that—despite your plethora of books and articles—I will remember these four words of yours above all others anytime I feel badly about my body or deny myself the human right of enjoying food.

“EAT THE FUCKING COOKIES!!!”

I love you, Alice. We all do.

Steven W. Thrasher

Steven W. Thrasher, PhD, CPT, a journalist, social epidemiologist, and cultural critic, holds the Daniel Renberg chair at the Medill School of Journalism, and is on the faculty of Northwestern University’s Institute of Sexual and Gender Minority Health and Wellbeing. A former writer for the Village Voice, Scientific American and the Guardian, Thrasher is the author of the critically acclaimed book The Viral Underclass: The Human Toll When Inequality and Disease Collide. [Photo by C.S. Muncy]