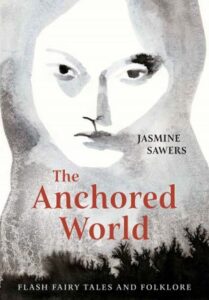

Reimagining Folklore and Fantasy: Nine Speculative Stories from Asia and the Asian Diaspora

Jasmine Sawers Recommends Lucy Zhang, Sequoia Nagamatsu, Priyanka Bose, and More

Fairy tales, folklore, and myth are often the first stories we are ever told. They become the blueprints to our understanding not only of storytelling, but the very values our cultures impart on us, whether conscious or unconscious. Cinderella tells us beauty is moral goodness but ugliness is moral decay. Little Red Riding Hood tells us not to talk to strangers. Countless Grimm tales tell us not to trust a woman or a foreigner.

What is it, then, to be inundated with the stories of people who don’t look or sound like you, who have different priorities or communities or familial structures from you? What is it to speak a colonizer’s language? To work in it, to write in it, to dream and read and live in it? To love it? How can we translate our own cultures onto the page, how can we find ourselves in stories never written to include us unless as villains—and how are we changing the very landscape of English language literature just by being who we are without apology?

So much of literature is about filling gaps—where can your perspective, your history, bloom? Especially if you’re queer, disabled, BIPOC, a religious minority, a marginalized gender? And especially when the story of marginalization in so much folklore is one of monstrosity?

These nine stories by Asian and Asian-diaspora writers exemplify the breadth and possibility of contemporary writing in the folkloric tradition. Whether upending narrative expectation in retellings of the old tales or introducing us to worlds entirely new to us, these subversive stories by writers to watch are by turns searing, celebratory, and devastating.

*

“Bluebeard’s Sister” by Lucy Zhang

In this twist on the Bluebeard tale, Lucy Zhang lends depth to the titular villain—French folklore’s most prolific serial killer—by giving him a sister to protect, a sister both grateful and loyal enough to clean up after him time and again. Despite this, Zhang lets neither character off the proverbial hook: Bluebeard is zestful and shameless in his lusts both for wives and for killing, and his sister is long-suffering but tolerant of what she views as his foibles. Zhang gives us a portrait of a dangerously enmeshed family for whom there is no bridge too far, prompting readers to confront what, exactly, they would do for the ones they love.

Lucy Zhang specializes in fairy tales and multimedia stories. Her chapbooks Hollowed and Absorption were published this year. Check out her website for more (especially the dazzling “Before Happily Ever After“), and follow her on Twitter @Dango_Ramen.

*

“The Woman Who Was Everything” by Seema Yasmin

Seema Yasmin, a woman who, indeed, seems to be everything, weaves a wholly new tale about the pressures placed on women to fulfill every imaginable need of the people around them. Balancing humor and cultural commentary, Dr. Yasmin brings her unnamed protagonist to her breaking point and shows us the awesome and terrible freedom beyond it.

Seema Yasmin is an Emmy Award-winning journalist, medical doctor, professor and author. Her most recent book, What The Fact, explores the importance of fact-based journalism in a world harmed by declining media literacy.

*

“Whiskey Over Barbed Wire” by Kiik Araki-Kawaguchi

Winner of the Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize, The Book of Kane and Margaret by Kiik Araki-Kawaguchi is a surreal exploration of love and rebellion against the backdrop of Japanese American imprisonment during World War II. Though each story in it seems to begin Kane and Margaret’s journey anew, readers carry with them the histories, triumphs, and hurts of all the Kanes and Margarets from before. “Whiskey Over Barbed Wire” tells the tale of a Kane who sprouts wings and becomes a smuggler of “frivolous” goods that keep his fellow prisoners’ spirits up. The loss of his wings at the hands of the guards—the loss of his dignity at the altar of racism—heralds the loss of his love and all the hope he might have had for the future.

Kiik Araki-Kawaguchi is a graduate of the University of California, Berkeley and Santa Clara University.

*

“The Peach Boy” by Sequoia Nagamatsu

Momotaro is a famous figure in Japanese folklore: a warrior born from a peach as a gift to an old childless couple. There are countless additions to his legend, innumerable iterations of his history, and Nagamatsu’s version slots effortlessly into the Momotaro canon with a gravitas that feels new and electrifying. In this story, we meet Momotaro as an adult in a comfortable marriage, his adventures behind him. The only thing he and his wife lack are children; she keeps giving birth early to shriveled peach pits. After many years of disappointments, Momotaro’s wife sends him on one last adventure to complete their family.

Sequoia Nagamatsu is the author of the Japanese folklore and pop-culture inspired story collection, Where We Go When All We Were Is Gone. His novel, How High We Go In The Dark, is a national bestseller that was shortlisted for the Ursula K. LeGuin Prize for Fiction.

*

“Cowgirl and Laundry Boy” by Celeste Chen

With the Chinese myth “The Cowherd and the Weaver Girl” serving as scaffolding, Celeste Chen delivers a powerful gender-swapped kick in the teeth. In Chen’s hands, the California gold rush, a time and place of so much pain and violence for indentured Chinese immigrants, becomes a space where Asian women can reclaim their strength, Asian men their gentleness, and all these indentured laborers their humanity. Triumph is tempered by the bitter knowledge that you can’t go home again.

Celeste Chen’s work has placed in Best Small Fictions and won prizes from X-R-A-Y Lit, Pigeon Pages, and Sine Theta Magazine. She is at work on her first novel, which explores age-old ideas of loyalty, leverage, home, and fate. Find her on Twitter at @celestish_.

*

“The Precipice” by Jiksun Cheung

In “The Precipice,” Cheung spins a new and heartbreaking story out of the tradition of the Festival of Ghosts. Cheung sets a chilly (and chilling) atmosphere even as readers are warmed by the protagonist’s palpable love for his child, but there’s a fox spirit about, and the veil between the worlds of the living and the dead is at its thinnest. The reader feels the tension rachet up, and though they may have an inkling of what they may be about to fall into when they reach the precipice in question, the truth comes as a devastating blow nonetheless.

Jiksun Cheung is submissions editor for SmokeLong Quarterly and editor in chief of The Bureau Dispatch. He lives in Hong Kong and is at work on a novel.

*

“Tales of the Devil’s Wife: Our Children” by Carmen Lau

That old lesson from Cinderella still dogs us: our culture trains us to distrust that which we deem ugly (and foreign, and different, and and and—). Ask for a description of a monster, and you might receive a list of disturbing physical attributes that become inextricable from what is monstrous in the creature’s actions. In this story, Lau asks us what true monstrosity is: an accident of physical appearance, or a rot within one’s character? Here, readers are confronted with the banality of evil—and how familiar its words are.

Carmen Lau is the author of a collection of fairy tale-inspired short stories, A Girl Wakes, the winner of the 2015 Electric Book Award.

*

“A Fable” by Sheena Raza Faisal

In this new tale that reads like the best of the old ones, Faisal manages to set her stage in the modern world without compromising the rhythmic lull of folkloric language. When a father mistreats and marries off his three daughters, his cruel and careless words become curses that condemn his daughters to living down to his worst expectations. When he is left alone without even the odd phone call from his children, he is beset by the harshness of the elements but has no idea that he is merely reaping what he has sown.

Originally from Mumbai, Sheena Raza Faisal now lives in New York.

*

“His Beloved Ianthe” by Priyanka Bose

Bose, a nonbinary transmasc writer, reorients the myth of Iphis and Ianthe as explicitly trans. Historically seen as a lesbian story despite the extremely trans premise of the “female” Iphis being raised as a boy to save his life, this iteration feels less like a reimagining so much as a removal of the cis-normative lens so often placed on it. Here we get the Iphis myth hewn to its core: a trans child reaches adulthood longing for a body that matches his spirit and is granted a gift from the gods in finally becoming whom he truly is.

Priyanka Bose is at work on their first story collection and can be found on Twitter @mspriyankabose.

_____________________________________

The Anchored World: Flash Fairy Tales and Folklore by Jasmine Sawers is available from Rose Metal Press.