Over the last 25 years I have been privileged to witness and photograph many historical events. From the fall of the Berlin Wall to Nelson Mandela walking out of prison to the toppling of the Saddam statue in Baghdad, and numerous other moments, my camera has led me around the world. Over the years, people would often ask if I kept a journal along with my images to remember all I had seen. My reply would simply be: “When I see the image, I can recall everything that led up to that image—the moment itself and all that followed.” My photographs were my journal.

In 2015, I discovered over 200 rolls of film that had been exposed but never developed, put aside and forgotten. With my publishing partner, Blurb, we decided to see what was on the film. The result was a transformational experience that forced me to re-evaluate the end of the analog film era and my photos as documents of memory. The physical degradation of the film visibly speaks to the passage of time but also changes the nature of my images from works of photojournalism into something else.

After the film was developed, it was digitally scanned, so my first encounter with these missing pieces of my work felt like an odd amalgamation of the digital and analog worlds. As the pictures downloaded, bit-by-bit because the files were so large, images took shape on my screen in a piecemeal fashion. It resembled the old, magical feeling of watching a print come to life in the darkroom. I had no idea what was on the film, so looking at each image appear on the screen was like the unraveling of a mystery: What is the image going to be of? Once I saw the image whole, there were two reactions. “Wow! I remember that, and this is what was happening.” Or, more often: “Wow! I don’t remember that, and I have no idea what was happening.”

(1) Soldiers in training, date unknown. The Lost Rolls Project.

(1) Soldiers in training, date unknown. The Lost Rolls Project.

Almost immediately, my belief in photos as an infallible form of memory crumbled. Image #1 is of a group of soldiers, bayonets at the ready, in what appears to be a training exercise. It’s a powerful moment, a decent photograph, and I would expect the memories to come rushing back. But there were none. Even though I’m sure I can research who they were, based on the weapons and uniforms, and what was going on, that really isn’t the point. Instead, I recognized that this was becoming a meditation on the documents we use to know and recall the past, especially the role that analog film has played in that process. I had expanded film photography’s inherent delay—between picture taking and image viewing—over a period of decades, and this experience forced me to question whether this is still the dynamic in the age of the instantaneously visible image. Is there something special to the tangible form of film? And to the ways that film literally carries the marks of time as it degrades? Does such degradation color the way we see the past? This project had become as much if not more about memory than about the specifics in a given found photo.

(2) Pro-Arafat rally. West Bank, date unknown. The Lost Rolls Project

(2) Pro-Arafat rally. West Bank, date unknown. The Lost Rolls Project

The physical effects of the passage of time appear brilliantly on image #2. I have spent a great deal of time covering the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, and yet here, all I can do is simply acknowledge that these are Arafat supporters at a rally at some point. The other details have been lost. What is remarkable about the image is how the mold snakes its way around the picture, creating its own lines and borders, a new frame (almost literally) for this photograph. Along the same lines is my image of former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, image #3. It’s a panoramic photograph with an odd color twist and light leaks resulting in an interesting portrait. This is the artistry of time.

(3) New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, date and location unknown. The Lost Rolls Project

(3) New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, date and location unknown. The Lost Rolls Project

But amongst the degraded images and lost memories, there are some photographs I clearly remember making. Image #4 is a simple photograph. It’s a brick wall with word “incident” written on it.

(4) “Incident,” Bijeljina, Bosnia, 2004. The Lost Rolls Project.

(4) “Incident,” Bijeljina, Bosnia, 2004. The Lost Rolls Project.

I had photographed some of the first war crimes in the Bosnian War in 1992 (image #5). Twelve years later, I returned to the exact scene of the executions and took this image of the place in question. The photo itself was lost until the film was processed, but I remembered that visit and that day in particular. I recall returning and seeing the wall and I recall a lesson I learned then about memory. This photo acts as a reminder of the ways memory can bend and warp—much like the degraded, warped images of The Lost Rolls.

(5) Arkan’s Tigers kill and kick Bosnian Muslim civilians during the first battle for Bosnia in Bijeljina, Bosnia, March 31, 1992. The Serbian paramilitary unit was responsible for killing thousands of people during the Bosnian war, and Arkan was later indicted for war crimes.

(5) Arkan’s Tigers kill and kick Bosnian Muslim civilians during the first battle for Bosnia in Bijeljina, Bosnia, March 31, 1992. The Serbian paramilitary unit was responsible for killing thousands of people during the Bosnian war, and Arkan was later indicted for war crimes.

Up until the point of revisiting the wall, I remembered the street along it as being a huge boulevard. I had thought I was protected by its vastness, safe from being seen when I shot those photos of the war crimes. But as I realized when I returned, and here again it’s reasserted through the found photo, the street is quite narrow and the danger had been far greater than I’d remembered. It was evident that I was most likely about ten feet away, standing alone in the middle of the street, photographing dying victims and their executioners.

(6) Alexandra Boulat, 1962-2007. The Lost Rolls Project.

(6) Alexandra Boulat, 1962-2007. The Lost Rolls Project.

Then there are the personal images—images of past relationships, and at least one picture that reminded me of an even more permanent loss. Seeing image #6 of photographer Alexandra Boulat, taken during a moment of happiness at the wedding of friends, was a powerful, bittersweet experience. Alex died in 2007, but in this photo she is full of life, just as I remember her. A photo can convey the passage of time while it simultaneously reaffirms prior joys.

(7) Location and date unknown. The Lost Rolls Project

(7) Location and date unknown. The Lost Rolls Project

Another striking moment is image #7. This one is a simple family portrait. The people look at me as though they know me, but I have no idea who they are. Yet their stances and the way they look into the camera feels so familiar. I even asked my family if they were relatives. In many ways, this image represents the idea of The Lost Rolls most clearly. It’s not an historic event. It’s not of politicians or other widely known individuals. These are the people who populate all of our lives. And by extension, these are the kinds of images that lay hidden in all of our drawers or cabinets, the undeveloped roll that has been ignored or forgotten. That roll may hold a child’s graduation or holiday celebrations or just a random get-together among friends. Those rolls hold memories. We may not have all the details of the who, what, or when. But the magical re-encounter with the past is a fascinating and phenomenal experience and holds the possibility of returning the past to us in visible form—versions of our selves, our friends, our family from long ago. We have moved away from the analog period, but still at this stage, each of us has those images—locked in our own lost rolls—waiting to be seen.

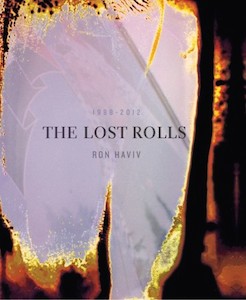

From The Lost Rolls, by Ron Haviv, available now.

From The Lost Rolls, by Ron Haviv, available now.

Ron Haviv

Ron Haviv is an Emmy-nominated and award-winning visual storyteller and co-founder of the photo agency VII, dedicated to documenting conflict and raising awareness about human rights issues around the globe.