On the night of the hanging, everything is as calm and orderly as it should be in a jail devoted to the safety and care of one very important man. All prisoners but one are asleep in their cells, restless, dreaming of their victims or their loved ones, which in most cases are the same people. The Rawalpindi sky is clear and full of stars; all the talk about omens is rubbish: there are no meteor showers, no storms brewing on the horizon, the sky is not going to shed tears of blood, the earth is not about to split open and swallow its wretched inhabitants and their grief.

The man who is awake has asked for a safety razor, claiming that he doesn’t want to look like a mullah in death. After consultations with superiors, the jail superintendent has sent for a barber, who shaves the man gently, making sure to clear the fuzz from his earlobes. The man asks for a cigar and the jail superintendent doesn’t need to ask for his superiors’ permission. No man who is about to be hanged in three hours and forty-five minutes has ever tried to kill himself with a Montecristo. The jailer makes sure to light it himself; the man chews on his cigar, takes two deep puffs and regrets it, thinking maybe he should have quit when he had the time. The man asks for his Shalimar perfume, sprays himself and lies down on the floor. A mosquito buzzes near his ear. On any other night he might have called in the jailer and given him a dressing-down for infesting his prison cell with poisonous insects, might have accused him of being a tool of the White Elephant, his favourite invective for the United States of America, but tonight he just shoos the mosquito away half-heartedly, listening to the rising and fading whirr of its wings. He is grateful for the company.

Everyone agrees on the above events. Those who wanted to hang him, those who wanted to save him, those who wanted a martyr in the early morning whose blood could help them bring about a revolution, even those who were indifferent, all agree up to this point that the man lay down on the floor, pulled a sheet over himself and stayed still, dress-rehearsing being dead.

Although everything was still and orderly in and around the cell where an about-to-be hanged man practised his death pose, there was activity, quite a lot of activity, around the country in some crucial spots. Many would later say, specially journalists and diplomats who made a living out of exaggeration, that it was the longest night of their lives, that they knew something historic, something catastrophic was about to happen. But only those who had been woken up without warning with a degree of rudeness would remember this night when their own time came. An imam was hauled up from his small room adjacent to his small mosque and ordered to get ready to lead the funeral prayers of a very important man. One of the world’s sturdiest planes, a C-130, was on standby at Rawalpindi air base to ferry the body to the man’s village. A military truck followed by six machine-gun-mounted jeeps made its way towards the airport, with some sleepy, some alert soldiers, their commander wondering why a dead man needed so much protection. Elites stay elite even in their death, he thought. Some soldiers sang a tea jingle: ‘Chai chahyie, kaunsi janab.’

‘Shut up,’ barked the commander. ‘We are on VIP duty.’ A caretaker at the village graveyard was asked to start digging a grave, and when he asked what size, he was slapped.

‘Your own size,’ he was told.

Above are the facts that everyone agrees upon. As with every hanging, there are differing accounts about the man’s walk to the gallows. How did he walk? Some say he never actually walked. That he collapsed on the shoulders of his jail guards and had to be carried. His jiyalas say that he walked on steady feet, head held high, climbed onto the podium as if addressing the nation one last time, kissed the noose and put it around his neck. Others say he was carried on a stretcher and two policemen, themselves shaking at the gravity of the moment, had to prop him up by his armpits before fitting the rope around his neck. You can’t hang a man when he is horizontal on a stretcher.

There was one oversight by the jail superintendent, but that was taken care of by the ingenuity of a captain who happened to be on the scene on a top-secret mission. After discovering that the jail administration had forgotten to order a coffin, the captain barged into the jail armoury, looked around, saw a body-sized wooden crate that was used to store the jail guards’ rusting guns, shouted at them for not having any respect for their weapons and handed the crate over to the jailer who, in gratitude, leapt forward to kiss his hands. The captain put his hands behind his back and reminded him that he was on post-hanging photoshoot duty and would like a few private moments with the body after the man was hanged. The jailer agreed, knowing he had no choice in the matter, and asked the captain if he would like to witness the hanging. The captain declined the offer, saying he wasn’t on hanging duty.

He was here on a different mission.

Before being taken to the waiting cargo plane, the hanged man was left alone in the jail superintendent’s office for a few minutes with the captain, who had brought a professional photographer with him. In those few minutes, the photographer had to perform the most shameless, and as these things go hand in hand, the most high-powered, assignment of his otherwise mediocre career. He pulled down the hanged man’s soiled shalwar and, with the flash on, took half a dozen photos of his genitalia. It was done in the forlorn hope of confirming the persistent rumour that the hanged man was not circumcised and hence a Hindu. The very fact that photos were never processed or released was proof enough that the man was indeed circumcised and hence a Muslim. The man himself might have argued forcefully that the one didn’t prove the other, that many Muslims in his hometown never bothered to circumcise their children. But this little episode ended when the captain made a phone call and reported that the bastard was dead and circumcised. There was a sigh on the other end of the phone. The director of Field Intelligence Unit’s internal security said that the bastard was lying and cheating even in his death. ‘And you, Captain, you had one job. What are we going to do with you?’ said the director and put the phone back on its cradle with historic disappointment.

The nation was thus spared the indignity of waking up to newspapers with pictures of a hanged man’s genitalia on the front pages.

The captain was punished with a transfer to a town where car number plates started with the letters OK and where people from far-off districts came to get their vehicles registered. The captain had done a brief stint in OK town cantonment after getting his commission three and a half years ago and knew that the vehicle registration plates were the only exciting thing about the city. He knew he would need to create his own entertainment and come up with a mission to shine on this punishment posting.

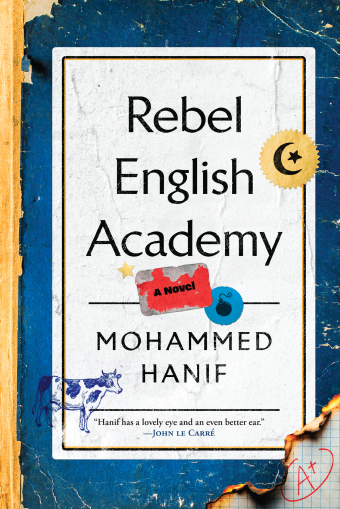

Three nights after the hanging, when our captain, let’s call him Captain Gul, is inspecting his room in the Bachelor Officers’ Quarters and testing the strength of his bed, all the while looking at himself in the dressing table’s smudged mirror, admiring a hint of a cleft in his chin, his wild side-burns and lush black moustache, a few miles away there is a knock on the door of the Rebel English Academy which, despite its misleading name, is a law-abiding and affordable tuition centre for basic English. Its founder and sole teacher, Sir Baghi, is about to receive a young lady guest he is not expecting at all.

__________________________________

From Rebel English Academyby Mohammed Hanif. Run with the permission of the author, courtesy of Grove Press. Copyright © 2026 Mohammed Hanif.