Rebecca Solnit on Setting Cinderella Free for Contemporary Readers

A Classic Fairytale Rebuilt as a Working Class Liberation Story

It began, as so many things do, with wandering in the public library. Mine has a used bookstore near the entrance, where I often browse, and one day not long ago I found a little print, a loose page from a broken book, for sale. It showed Cinderella as a cheerful barefoot girl in a ragged, patched blue dress, holding a huge orange pumpkin with both arms. I bought it, thinking I might eventually give it to a child, possibly to my magnificent great-niece Ella (and only while writing this story did I realize that without the cinders Cinderella is also an Ella).

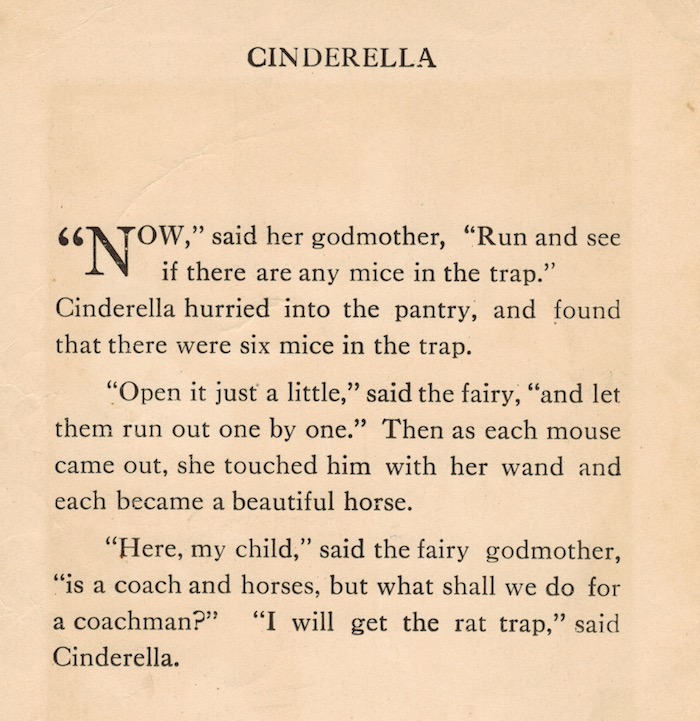

Later on, I looked at the backside of this image from a book of fairytales. It had a bit of one version of the Cinderella story on it. And after the fairy godmother has turned mice into horses and the pumpkin into a coach, this interchange appears: “Here, my child,” said the fairy godmother, “is a coach and horses, but what shall we do for a coachman?”

“I will get the rat trap,” said Cinderella. That passage, in which mice and rats change form, was striking, as was Cinderella’s active collaboration in bringing about the metamorphosis. I realized that this was a story about transformation, not just about getting your prince. And about other relationships, including the one between Cinderella and the fairy godmother. One thing led to another, and I decided to rewrite it for Ella (to whom Men Explain Things to Me is also dedicated) and began musing on possible mutations to introduce. The questions were how to preserve something of the charm of transformation and the plight of the child, and how to work out a more palatable exit from her plight than the one we all know.

One of the things the cake shop gives Cinderella, aside from independence, is the power to benefit others, because it’s also a meeting place.

Once I’d begun rewriting it, I began looking at illustrations and found and fell in love with the English illustrator Arthur Rackham’s images for C.S. Evans’s 1919 retelling of the story. Rackham is one of the great children’s illustrators from the golden age of children’s picture books, and he made images for everything from the classic fairytales to more contemporary children’s books such as Peter Pan and The Wind in the Willows (and some pictorial editions of adult books, including Gulliver’s Travels and The Compleat Angler). His color work is often full of moody, drab colors and subtle tones, thickets, forests, tangled vegetation, delicate human, fairy, witch, and animal beings who seem to always be turning, fleeing, striving, flying, reaching, twining like vines through the tinted spaces he set them in. The silhouettes are bolder and simpler.

I’ve always loved Rackham’s work and am thrilled to share it with a new generation. Evans’s retelling is sentimental and rife with ideas that virtue and beauty and upper-class status are more or less the same thing, and the least charming aspect of Rackham’s images are the portraits of the stepsisters as preposterously awkward, ugly creatures, and we did not use those here. But there are other wonders and glories in his illustrations, aside from their sheer beauty. Silhouettes meant that the story might not feel so racially determined as the other images by Rackham (I was amused that some people first mistook the century-old images for those of the present-day Black artist Kara Walker or thought they were rip-offs of Walker’s more scabrous, scathing work with silhouettes—which is itself a conscious nod to the popular silhouettes of another era).

I was also touched by Rackham’s image of the ragged child at work and thought of unaccompanied minors from Central America and immigrant domestic workers, who are a strong presence where I live, of foster children, and of all the children who live without kindness and security in their everyday lives, all the people who are outsiders even at home, or for whom home is the most dangerous place, or who have no home.

I liked the spirit of this silhouette-girl that Rackham portrayed. Even in rags she is lively, and she labors with alacrity, and runs and frolics wholeheartedly. She is stranded but not defeated. When it came time to write her story for our time, it seemed to me that the solution to overwork and degrading work is not the leisure of a princess, passing off the work to others, but good, meaningful work with dignity and self-determination—and one of the things the cake shop gives Cinderella, aside from independence, is the power to benefit others, because it’s also a meeting place.

We are also in an age in which marriage is not how women determine their economic future or their identity, and so marrying the prince was going to have to go, too. Besides, the prince also seemed to need liberation. In the end, even the stepsisters needed to be set free, and if the stepmother was irredeemable, it’s because she’s all of us: insatiable craving and its underbelly, selfishness incarnate. She’s who we all are when we feel poor amid plenty.

I wanted to set everyone loose to be their best and freest selves.

I wanted a story about liberation, about, as Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor put it in another Haymarket book, “how we get free”; or, as Buddhists sometimes put it, “the liberation of all beings.” I wanted a kinder story, and I took from many other fairytales the theme about being kind to animals as a good thing to do because it’s part of being a good person, but also a handy thing to do since they may return the favor. I wanted to set everyone loose to be their best and freest selves. It’s why the book’s title is Cinderella Liberator, a phrase that carries hints of Katniss Everdeen and Imperator Furiosa and the women of Hong Kong action films like House of Flying Daggers and The Heroic Trio, those powerful women who seize control of the means of production and destruction and move through the world like lionesses.

I wrote the story first for Ella, and then for anyone and everyone who loves the old stories in which mothers become trees and brothers become swans, in which animals hold conversations and girls open their mouths to speak and jewels and pearls spill out, in which magic models the work of transformation we all have to do for ourselves, on ourselves, all the time, and in which the huge tasks life sets us are clear and dramatic.

It’s still for Ella and for her younger sister, Maya, and their mom, my first niece, Amanda. For Sam, Kat, and Atlas, who love a good story; for Charlie, Elena, Berkeley, Dusty, and Oscar, who were among the early readers; Ana Teresa Fernández, who was the very first reader and whose powerful performance project in which she made Cinderella’s shoes out of ice and wore them until they melted was a more ferocious rewriting of the story (a print of one of those ice shoes with her foot in it has the place of honor in my home; I have been living with Cinderella revisionism for a long time).

And it’s for my grandmothers, Julia Walsh Allen and Ida Zacharias Solnit, both of whom were motherless girls, neglected, undereducated; neither of whom quite escaped that formative immersion in being unloved and unvalued; both of whom are long gone, though the repercussions of their devastation linger. My maternal grandmother, Julia, whose immigrant mother died in childbirth, was raised by relatives in Brooklyn. Her education stopped in 6th grade, after which they made her work full time as a laundress while her girl cousins continued with their education. My paternal grandmother, Ida, was an unaccompanied refugee child who, after years without parents, made it from the Russian-Polish borderlands to Los Angeles with her younger brothers when she was fifteen. There, her long-lost father and stepmother also treated her as a servant. Their tragedies were a century ago and more, but this book is also with love and hope for liberation for every child who’s overworked and undervalued, every kid who feels alone—with hope that they get to write their own

__________________________________

* “Cinderella” is a very old story, one version of a primordial story of the abandoned child who wins her way back to well-being (or, as the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Classification of Folk Tales has it, #510A, the “Persecuted Heroine”). In 1892, Marian Roalfe Cox compiled a book titled Cinderella: Three Hundred and Forty-Five Variants of Cinderella, Catskin, and Cap o’Rushes, Abstracted and Tabulated. There are ancient Egyptian and Greek versions, a Chinese version from the 9th century with a magical fish and golden shoes, a 12th-century French version, and various folkloric versions in Norwegian, German, Italian, and other European languages. In the Norwegian version, a talking bull with magical powers takes the place of the stepmother; in the German “Aschenputtel,” a tree grows on the grave of the dead mother of the heroine and fills with birds, who aid her and give her a gold and silver dress—and later peck out the eyes of the stepsisters. In the Russian version called “The Wonderful Birch,” the tree that grows out of the mother’s grave becomes the returning mother. There are violent and vengeful versions, versions with evil witches and no fairy godmother, annoying modern versions focused on marrying up, and dozens of new variations among children’s books. And now, one more, with gratitude to everyone who’s taken the time to read it.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Cinderella Liberator. Used with permission of Haymarket Books. Copyright 2019 by Rebecca Solnit.

Rebecca Solnit

Writer, historian, and activist Rebecca Solnit is the author of more than twenty-five books on feminism, western and urban history, popular power, social change and insurrection, wandering and walking, hope and catastrophe. Her books include this year’s No Straight Road Takes You There, as well as Orwell's Roses, Recollections of My Nonexistence; Hope in the Dark; Men Explain Things to Me; and A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster. A product of the California public education system from kindergarten to graduate school, she writes regularly for the Guardian and serves on the boards of the climate groups Oil Change International and Third Act.