Rebecca Solnit on Her Most Beloved Objects

A Field Guide to the Artifacts from "A Field Guide to Getting Lost"

In A Field Guide to Getting Lost, the book-length meditation on loss and getting lost I published twenty years ago, I describe the film I made at age twenty in an abandoned hospital with the young man I got to know through that project and then spent the rest of my twenties with; this is the lone surviving prop from the film, inscribed with a line from Nabokov’s Pale Fire: The lost glove is happy.

The first time I got drunk was on Elijah’s wine. I was eight or so. It was Passover, the feast that celebrates the flight from Egypt and invites the prophet into the house. I was sitting at the grown-ups’ table, because when my parents and this other couple joined forces there were five boys altogether, and the adults had decided that I was better off being ignored by their generation than mine. The tablecloth was red and orange, cluttered with glasses, plates, serving dishes, silver, and candles. I confused the stemmed goblet set out for the prophet with my own adjoining shot glass of sweet ruby wine and drank it up.

Those are the opening sentences of A Field Guide to Getting Lost. I am pretty sure that these battered silver candlesticks that are now mine were on that table, and the candlesticks and I are the lone survivors of that Passover meal. (The dinner table survives but never mind that. Meal sounds more the event than the furniture, which table suggests.) The chapter veers off to contemplate Elijah, the prophet for whom doors are left open on that day, and on what it means to open the door to the unknown. And to wander in remembered as well as actual landscapes, to converse with ideas and stories and songs as well as people.

Your whole life is a research expedition, collecting specimens and building your pattern-recognition skills as you accumulate experiences and ideas about them, or at least mine has been. Around the time my book A Field Guide to Getting Lost appeared in 2005, I tried to reorient a class of wonderfully, frustratingly diligent journalism students who had been trained that writing begins with rushing outside to gather material, that you’re starting from scratch every time. Turning journalists into essayists in that long-ago class meant turning them from people devoting most of the time they had to collecting new material into hunter-gatherers in their own memories, experiences, and interpretations, curators in the natural-science museum of their heads, or at least trying to do so.

That’s been very much how I work most of the time, and often for my political writing one new incident (often a nasty one) will become a catalyst that reorganizes ideas, observations, collections I’ve been accruing for a while, and I’m ready to write something. Or an overarching theme will turn the bricolage of years into a coherent set of touchstones for an essay. That’s how A Field Guide to Getting Lost came together, my most personal book when it came out twenty years ago, and a big departure from the kind of writing I’d been doing before. Penguin is releasing a twentieth anniversary edition this month, with an afterword in which I note:

A number of things had led to the writing of this book. One was that my earlier book with Viking, Wanderlust: A History of Walking, had touched on meandering and being out in the world to encounter the unknown and the unpredictable, but it felt like there was far more to explore about this theme (especially since we were entering an era, even then, of more digital aids to navigation and more reluctance to wing it). Another was that I had been writing books governed by what I could call the rules of daylight—narratives organized by chronology, analysis, argument, data drawn from research—and I wanted to write by the rules of night, by association and intuition, the kind of freedom that I associate most with poetry.

With ideas about loss and getting lost as my compass and map, I began assembling some entirely new material, about everything from navigational strategies and search and rescue stories to captivity narratives. It’s a slim book in nine chapters that includes mentions of the Wintu, Chemehuevi, Mohawk, Iroquois, Seneca, Comanche, Achumawi, and Yokut peoples; cites Yves Klein, Simone Weil, Cabeza de Vaca, Daniel Boone, Isaac Dineson, Djuna Barnes; discusses punk rock and ruins in the 1980s, visits to places around the west, including Joshua Tree, Galisteo, the Rockies, the Great Salt Lake, the Tomales peninsula; tule elk and coho salmon, a tortoise in a dream and encounters with desert tortoises, bluebelly lizards, flowers bending under the weight of bumblebees, describe the violent hatching out of butterfly chrysalises, the metamorphosis of Tiresias from a man into a woman after he struck a snake–all this various stuff woven into the musing and meandering narratives in which my disappeared great-grandmother and my desert lover are among the others who appear.

Much of it was from memory, but in museums, I toured the medieval and early renaissance galleries looking for the blue of distance, that representation of the way that distant places and the phenomena in them look blue—

The world is blue at its edges and in its depths. This blue is the light that got lost. Light at the blue end of the spectrum does not travel the whole distance from the sun to us. It disperses among the molecules of the air, it scatters in water. Water is colorless, shallow water appears to be the color of whatever lies underneath it, but deep water is full of this scattered light, the purer the water the deeper the blue. The sky is blue for the same reason, but the blue at the horizon, the blue of land that seems to be dissolving into the sky, is a deeper, dreamier, melancholy blue, the blue at the farthest reaches of the places where you see for miles, the blue of distance. This light that does not touch us, does not travel the whole distance, the light that gets lost, gives us the beauty of the world, so much of which is in the color blue.

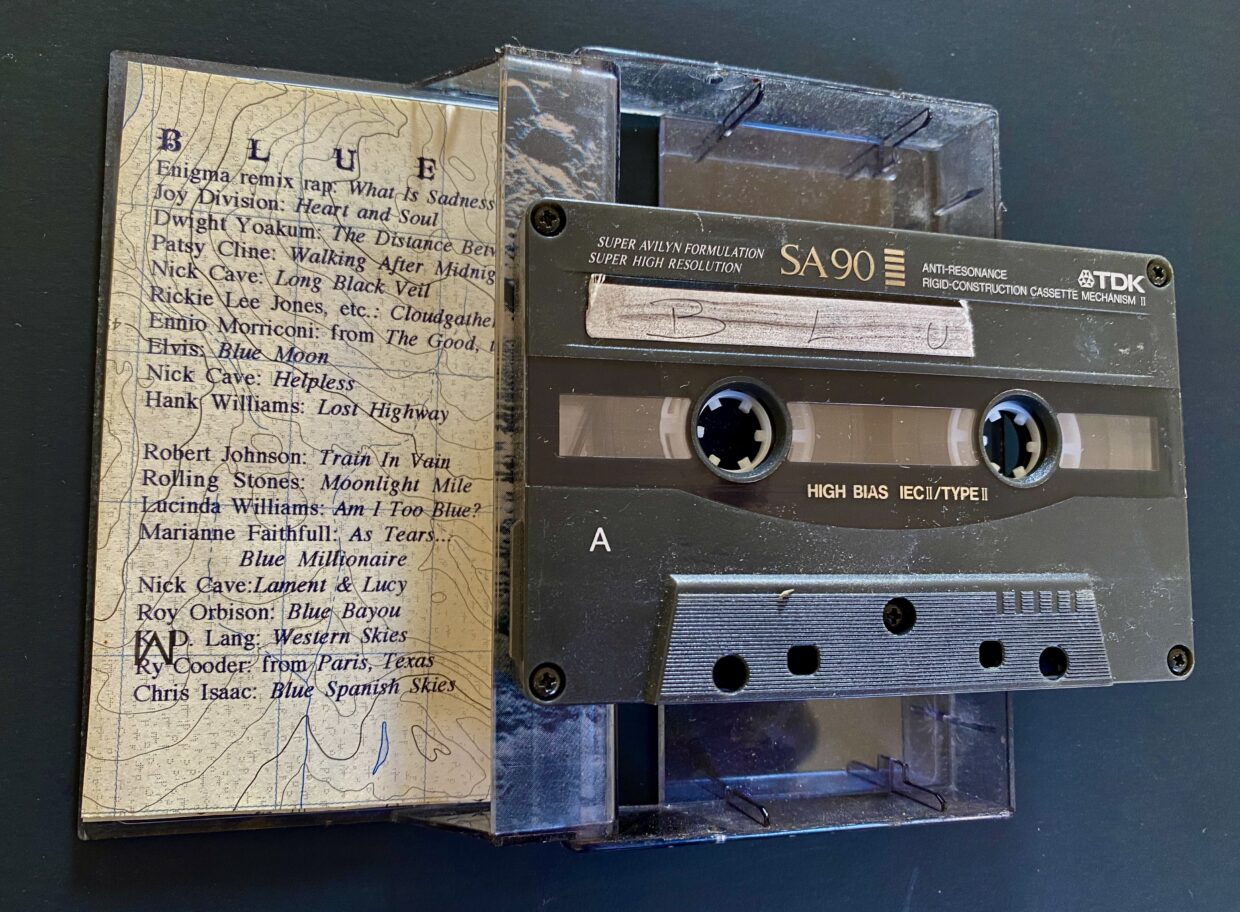

That opening passage about the blue of distance became the most quoted part of the book, posted by Beyonce on her blog after Blue Ivy Carter was born, and a ballet and a number of pieces of music have been named “The Blue of Distance” after it. The phrase came from a compilation cassette I had put together many years earlier, when cassettes I could play in my Chevy pickup truck were my preferred sources of music, and compilations were something lots of people I knew put together. Not from the word written on the cassette but from how the songs made me think about blueness and distantness and their relationship. I still have the cassette but no means to play it.

Blue was the title I gave a compilation tape I made a dozen years ago, and some of the songs were about sadness, some about the sky, some about both. Every once in a while I made a collection like that, mostly to be listened to on long road trips, and in them I tried to define what it was that moved me in the music I chose. In Blue, most of the music had some relationship to the blues, as if the music was going back to its origins in longing and the blue of distance.

I have an archivist’s heart; I don’t want anything lost to posterity; feel wistful about the ephemerality of cloud formations, want to preserve the way the shadow of the bird passes over the child; and I also know that so much will be lost, no matter what, that memory starts by being selective and ends by fading; that what can be recorded, including as writing, is a tiny bit of what transpires. But this book might be unusual in that I have so many material relics of the stuff in the text.

That section, the first of the four interleaving “Blue of Distance” chapters, also had this passage,

One day a few years ago my mother took out of her cedar chest the turquoise blouse she bought for me on that trip to Bolivia, a miniature of the native women’s outfits. When she unfolded the little garment and gave it to me, the living memory of wearing the garment collided shockingly with the fact that it was so tiny, with arms less than a foot long, with a tiny bodice for a small cricket cage of a ribcage that was no longer mine, and the shock was that my vivid mem- ory included what it felt like to be inside that brocade shirt but not the fact that inside it I had been so diminutive, had been something utterly other than my adult self who remembered. The continuity of memory did not measure the abyss between a toddler’s body and a woman’s.

My mother is thirteen years gone, the cedar chest is mine, and the Bolivian blouse resides in it, though I had the pleasure a few years ago of seeing my youngest great-niece romp around my home in it.

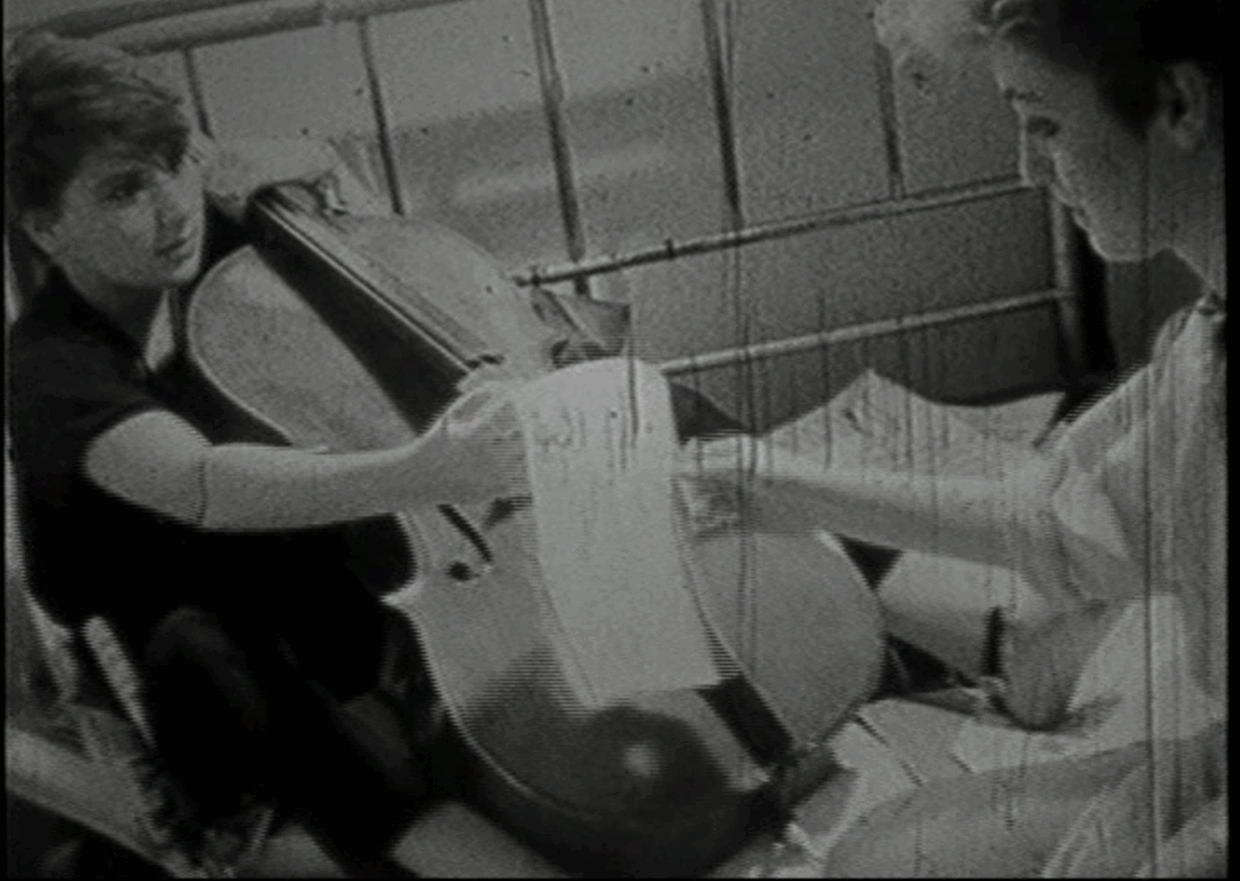

The fifth chapter, titled “Abandon,” begins by describing the abandoned hospital which I explored with the young man I’d spend my twenties with when invited me to make a film with him in its corridors and chambers of eerie decay. He had immense technical chops—the black-and-white Super-8 film we made is elegantly edited, especially for a twenty-one-year old’s first venture into the medium—but needed someone to come up with a storyline. I did, from a dream I’d had and the influence of Mervyn Peake’s fantasy novel Gormenghast, about a perilous hospital that was supposed to be infinite, a version the dystopia of ruin and chaos that made so much sense in the early 1980s, an age of industrial ruins. I played the young patient trying to escape the various menaces, and our friends co-starred, but the film was more about exploring the ruins than the plot. And the chapter is centered one of those co-stars, my friend Delphine, who would’ve just turned 17 when we made the film. In one scene she hands me a map and compass when I stumble upon her playing her cello—she was a trained classical cellist and a bass player in punk bands, a brilliant musicians and a wild young woman.

The biggest change I made for the twentieth anniversary edition was to restore Delphine’s real name–at the time I wrote the book, a pseudonym seemed right –and to dedicate the book to her. She had died of an overdose in 1989, a devastating loss for me and many others. In the afterword, I wrote “I think of Delphine as having died, in some sense, from a world that didn’t have a place for her with her immense talent, her restless intelligence, and her queerness. Had she lived, she would be sixty the year of this twentieth-anniversary edition, and though misogyny is not all gone in the music industry or anywhere else, I think there is more room for people like her, sometimes, in some places.”

I wrote that she “was a delicate tomboy, sultry and pale, with the soft perfect skin of a child and fierce dark eyes better described as long than large. I remember a furtive look she had, of a cornered animal, and how elegant she’d become that last night. People wanted to capture her, like a wild thing, and take care of her, like a child. Beauty is often spoken of as though it only stirs lust or admiration, but the most beautiful people are so in a way that makes them look like destiny or fate or meaning, the heroes of a remarkable story. Desire for them is in part a desire for a noble destiny, and beauty can seem like a door to meaning as well as to pleasure. ”

Delphine’s eye, circa 1983,

Delphine’s eye, circa 1983,

The afterword is accompanied by a portrait of Delphine by Paki Robinson Mowry, a photographer friend of mine in that era, and in that image Delphine is wearing the lace mitts I made and some of my bracelets. I still have the mitts, a souvenir of that proto-goth New Romantic style we mixed with punk-rock studs and leather. In that chapter I recounted her ending, an overdose thanks to malignant friends, the kind of death that NarCan could and does reverse, but it wasn’t widely available back then.

She looked radiant, and I believed her when she told me she was off drugs. We were out on a Saturday, and she was meeting a woman on Thursday; she wanted me and her male companion to come too. She was more insistent about this date than usual, and she called me up that Tuesday, partly to see if she’d left her shirt and sweater in my car and partly to confirm that she’d call me Thursday morning at ten to set up our rendezvous…. Such clarity and commitment were unusual, and so when she didn’t call, I called her band’s house, the house she’d been living at the last few weeks. Marine had died Tuesday night, the older musician said, and he was broken up over it. “Little Delphine,” he said, “I can’t believe it.” …I folded up the violet shirt and sweater she’d left in my car and put them in the chest at the foot of my bed. They are still there. In the shirt pocket I found the crumpled wrapper of a Tootsie Pop.

I went to see her grave not long ago, stood at it remembering her burial, told her she was still remembered, still loved, took a picture, and only when I got home and looked at it did I realize I had shown up on what would have been her sixtieth birthday. I was glad that in addition to that modest marker, to which I’ll bring some flowers next time, she’s got a book dedicated to her now.

______________________

Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost, 2oth anniversary edition, is available now from Penguin Books.

Rebecca Solnit

Writer, historian, and activist Rebecca Solnit is the author of more than twenty-five books on feminism, western and urban history, popular power, social change and insurrection, wandering and walking, hope and catastrophe. Her books include this year’s No Straight Road Takes You There, as well as Orwell's Roses, Recollections of My Nonexistence; Hope in the Dark; Men Explain Things to Me; and A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster. A product of the California public education system from kindergarten to graduate school, she writes regularly for the Guardian and serves on the boards of the climate groups Oil Change International and Third Act.