Rebecca Makkai on Progress, Misogyny, and #MeToo

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

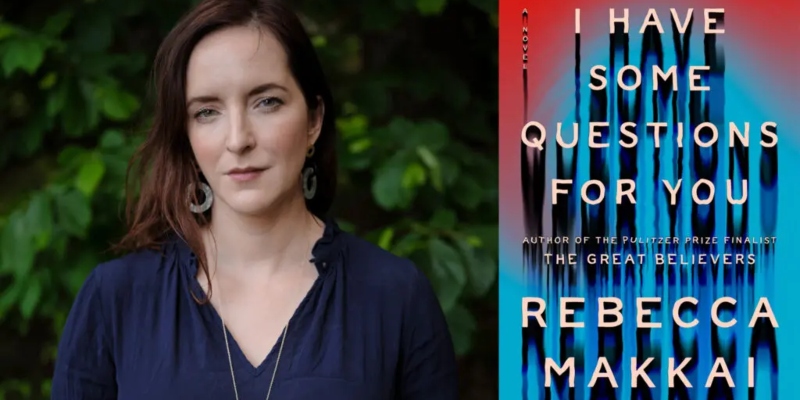

Novelist Rebecca Makkai joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to talk about new accusations of sex crimes or sexual misconduct, this time leveled against comedian Russell Brand, actor Danny Masterson, and Spanish Soccer Federation president Luis Rubiales. Makkai observes that since the start of the #MeToo movement, more people are willing to take such accusations seriously, but also describes the repetitive nature of the abuse as discouraging. She reads from her recent novel, I Have Some Questions for You, which, in part, asks readers to reconsider the way they think of sex, class, and race.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

Whitney Terrell: Each of the cases that we cited in the intro have, for me, specific echoes of cases that began the #MeToo movement. And also with the plot of your most recent novel, I have some questions for you. For instance, Danny Masterson was convicted of rape, he’s going to prison. How does that compare to Harvey Weinstein, who was also convicted of rape and is in prison now, as his case was the original impetus behind this whole movement? I mean, are these cases parallel, can we learn anything from their repetition?

Rebecca Makkai: I don’t think it’s a shock to anyone that this is repetitive. It was certainly that repetition and that repetitiveness that was really on my mind as I wrote this novel, but also in the years in which I wrote the novel. So I started thinking about this book in 2018. And that was when this initial wave of stuff was happening. They’re not all going to be exactly the same. And that’s where we have to be careful about saying, “Well, this one’s not as bad” or “this one is different.” We have to have room to make those distinctions. But that doesn’t mean we are using those distinctions to diminish. Which is a tricky balance.

WT: One of the things that I was thinking about the parallels between Masterson and Weinstein is that Weinstein was protected by the old boy network of Hollywood, right? He had power. He was a producer. And so people were afraid to say things about the assaults that he made on them, the women.

And the similar thing with Masterson, although in his case, it was the Church of Scientology, because he’s a member there and the teachings of the church are that you shouldn’t report these kinds of things to the police or report anything outside of the church. And so the women who were involved in eventually making these allegations said that they had all felt discouraged directly by the church or implicitly by the church from reporting what Masterson was doing, and it seemed like that happened also in the Weinstein case.

RM: Yes. But what’s interesting is that, what has happened in both cases, is that people have eventually talked. That doesn’t mean people are always going to feel free to, they’re not always going to be listened to. But this is what’s shifted in the past six years, five years, right? There were two things that really surprised me a lot. Well, there were many things. But the two main things that really surprised me about #MeToo: one was that it lasted. Because I really thought it was going to be like, two days of this internet hashtag. And then we were going to go back to not caring about this stuff, and not listening and not believing stuff. So that was number one.

Number two was the way that people were digging down. It wasn’t just famous people. And it wasn’t just the big capital T traumas. It was more nuanced. Maybe not necessarily prosecutable things, but people talking about, “Hey, this stuff happened in high school, this stuff happened in college, and it really upset me.”

And I guess three, tying those all together, is that people were listening. It was not just about people expressing themselves. It was also about people listening – and certainly not everyone’s listening. Certainly not everyone feels free to speak. Certainly we’re not getting this all out there. But the understanding that I think we’re starting to have in these cases – and maybe social media is part of this, you can reach a bigger audience faster when you have a problem – but we’re starting to have this understanding that people might at least listen. That’s new. That’s huge.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: And I feel like one sign of this… RIP Twitter. We’ve already talked about this, but I do feel like I log on to X, and –

WT: Sugi, have you arranged for us to pay for Twitter now? We don’t have a lot of funds. We’re gonna have to sell real estate, the podcast real estate.

VVG: No. We’re not…no.

VVG: The things that are trending, by the way – which is one of the reasons for “RIP Twitter” – only like 50 percent of them, or maybe less, are even pertinent. But Russell Brand was trending recently. And he started as a comic who often talked about his drug and sex addictions, and he was in Forgetting Sarah Marshall in 2008. And then as one does, he set up a YouTube channel in 2013. I do not [have a YouTube channel], but anyway, Russell Brand does, and he became a hero –

WT: You do too have a YouTube channel, Sugi! We were just talking about this.

VVG: We have a YouTube channel. Anyway, he became a hero of the left in Britain. And then as one does, he shifted and became a vaccine denier and conservative nut job. And then in September, four alleged victims accused him of rape, sexual assault and emotional abuse during a five-year period from 2006 to 2013. Is there an earlier #MeToo figure who reminds you of that narrative arc?

RM: Yeah, no, definitely. You look at someone like Bill Cosby before #MeToo–

WT: That’s who I thought of…

RM: Right. And we had years before #MeToo, and there was this pile up of all these women. I remember, there was a cover of some magazine. I can’t remember which one – I don’t know if it was their pictures or their names…

VVG: It was New York Magazine.

RM: Lord knows how they felt about that. That was probably a problem in and of itself. But one of the effects… it’s all these women. All these women are saying the same thing. We were not – when I say “we” I don’t mean “me,” but, this aside – we weren’t ready to go, “Oh, my God, this is clearly real.” There was still that, “Well, but they’re all in it for the same thing,” which is fame and glory, or whatever it was that people thought. Fast track to wealth and success. But maybe there’s been a shift. I don’t want to sound pollyannaish, believe me, but maybe there’s been a shift to more of us sooner, more publicly believing when these stories come public.

VVG: I think that I was actually thinking of a different magazine story, which actually illustrates the shift that you’re talking about. I think it was the New York Magazine that had a bunch of accusers on the cover, kind of supporting that case, which was more recent. And so this makes me want to dig up the earlier story that you’re talking about. But even just the notion that similar imagery would be portrayed for almost opposite reasons. Like, in the first instance, some sort of subtext of “name and shame,” like the nerve of these women saying this thing?

RM: I don’t think that’s what New York Magazine was doing. That was not my impression. I think they were saying, “Look at all these accusers.” I think it was like “Look at all these women saying the same thing.” Standing with them.

VVG: So we are talking about the same story.

RM: I think we are talking about the same story. I mean, it’s one thing to come forward. It’s another thing when your name or image is put on the front of New York Magazine. Like, you wonder how they felt about that. Because of course, they are not in it for the fame and glory, quite the opposite. No one wants their name known in this regard. So it’s more just like, “God, I wonder what the underbelly of that was,” and the effect for those women.

But, no, this is the story where they were like, “Look at this army of women all saying the same thing,” and that had a profound effect. At that point, I certainly didn’t need to be convinced, but I was like, “What is wrong with us societally that when this many people come forward – which should also be the case even if one person comes forward – but this many people come forward all saying the same thing, and we’re still not believing them. What is wrong with us?” Although I was probably one of the last people who needed convincing, that still hit me really hard when that appeared.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Madelyn Valento. Photograph of Rebecca Makkai by Brett Simison.

*

I Have Some Questions for You • The Great Believers • The Hundred-Year House • The Borrower • Music for Wartime

OTHERS:

Fiction/Non/Fiction, Season 1, Episode 2: “Jia Tolentino and Claire Vaye Watkins Talk Abuse, Harassment, and Harvey Weinstein” • Fiction/Non/Fiction, Season 1, Episode 22: “Alice Bolin and Kristen Martin on the Problem With Dead Girl Stories” • “Russell Brand’s Timeline of Scandal and Controversy,” by Alex Marshall, New York Times • “Danny Masterson sentenced to 30 years to life in prison in rape case,” by Alli Rosenbloom, CNN • “Luis Rubiales resigns as Spanish soccer president following unwanted kiss with World Cup winner Jennifer Hermoso,” by Issy Ronald, Homero De la Fuente, Patrick Sung and Zoe Sottile, CNN • StoryStudio Chicago

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.