Rebecca Fisseha on #MeToo in Ethiopia and Eritrea

When Women Who Survive Split the World Open

As a rule, I don’t follow anonymous social media accounts, except for @shadesofinjera. With smart, daring prompts, it always gets its 50K+ habesha (Ethiopian and Eritrean) followers talking about issues rarely discussed, taboo, or flat-out denied in the community.

This January, I was even compelled to send a DM to @shadesofinjera to express my gratitude and relief for the latest prompt: Tell us about the R. Kellys in our community, which had brought forth hundreds of habesha women’s personal stories of surviving childhood sexual abuse—an outpouring I never thought I’d live to witness.

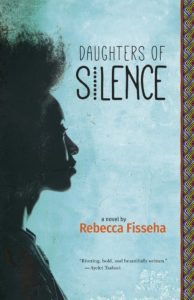

I spent hours glued to my phone, reading every single story. I was about to turn in final edits for my debut novel Daughters of Silence, about a female habesha survivor and her first painful steps towards recovery, against a backdrop of grief. The years of dithering and backtracking as I wrote the novel now felt like a blessing that allowed its completion to sync up with this moment-within-a-moment.

Fifteen months earlier, the #MeToo movement had hit the mainstream, but I had not felt a strong connection to it because the discussion of children’s abuse, particularly one led by women who were once little habesha girls like me, was absent. But sometimes it takes the right person asking the right question at the right time to get people talking. In a way, Tarana Burke had been to young American girls of color in 2006 what the person behind @shadesofinjera had become for habesha girls and women in 2019.

I had written Daughters of Silence with the hope that it would reach just such women. Although they were nowhere to be seen or heard as a group—over eight years of going through various kinds of therapy, I had met only one other habesha woman survivor—they had to be out there. Surely, my main character Dessie, like me, was not the only habesha girl who had grown up with a painful secret, “…forced to keep giving her favorite adult the wrong answer because he didn’t know how to ask her the right question.”

The stories submitted in response to @shadesofinjera’s prompt confirmed that she wasn’t. I felt seen. I also felt disappointed and sad, because all the stories on that Instagram thread were anonymous. But I understood why. To any survivor, coming forward with one’s story, even thinking about doing so, is frightening. To paraphrase the poet Muriel Rukeyser, it feels like the world will split open. In habesha terms, that means exposing self, family, community, and culture to shame.

The world could split open like a flower in bloom, like a woman shattering the glass that had separated her from true connection.The women’s need to remain anonymous was evidence of the ingrained fear of such a consequence. I was not immune to the fear either. If the manuscript of Daughters of Silence ever became a book, it was going to be frightening enough to say, I wrote about this, forget I wrote about this because I know about this. That was why I went with what to me was artistically more challenging and rewarding, yes, but also less intimidating: the semi-anonymous filter of fiction.

The problem was that fear, the cause of death for any kind of creativity, was also lethal for writing about this. Three years into the manuscript, my writing mentor sent me this note:

…much of this manuscript feels like it protects someone, something, some mode, or a cultural inheritance…the truth is missed here, in part because it must be v painful. The pain of diaspora, the pain of the patriarch who loses his child, the pain of the abandoned child, the pain and silence of women—it is all gestured toward, it is all touched. But not held…Go deeper. Be daring.

I’d not been seen so much as found out. The timing was divine, though. I was receptive to the criticism because a couple of months earlier I had been on the receiving end of a similar evasiveness. I had asked my widowed father a key question about my mother, a question directly connected to the reason I’d begun writing the book in the first place, and gotten a response whose silences echoed my own.

Years earlier, from the moment I found out that my mother was not being buried in our native Ethiopia but in Europe where my parents had lived as expats for the past 11 years, the ringing question in my mind had been why were we not burying her in Ethiopia?

In the novel, the adult Dessie, faced with a monumental question of her own which she believes that only her father can answer truthfully, encourages herself thus: It is a question I have to ask. The sooner the better. We’re still in that raw phase where it is possible to ask anything. A mere month into grieving, she asks. Unlike me, who was too muted by layered traumas—of new motherlessness, renewed proximity to my abuser, mourning my mother in a foreign land, then abandoning her to it—to ask before the funeral.

Instead, I turned to fiction for wish fulfillment, creating a character who tries to “Ethiopianize” a Canadian burial ground by transplanting soil and a sapling from Ethiopia. Of course, complications ensue. Complications which kept me busy but made for one lousy manuscript.

Thankfully, Ethiopian Orthodox traditions around death provide many opportunities to approach the hard questions for someone who needs them. These opportunities present themselves as a series of memorials, each requiring a gathering: Third Day, Seventh Day, Forty Day (the focal point for the action in Daughters of Silence), 120 Day, 180 Day, Annual, Seventh Year, and Fourteenth Year.

I also began disclosing that I am a survivor to people in my innermost circle of chosen and blood family.My mother’s Seventh Year came around. I turned in the latest draft of my manuscript to my writing mentor and went to Ethiopia for the memorial—my first time back since she died. In my maternal grandparents’ home, the extended family’s headquarters, I sat next to my father on the same couch where I had lain as a baby for pictures after my christening. We were surrounded by people who had known my mother since she was a girl, by women who told me they had cooked her wedding feast. I finally felt like I was attending my mother’s true funeral, and getting a second, possibly last, chance to ask. So, I did.

My father’s answer to the question of why my mother wasn’t buried in Ethiopia was unsatisfying, packaged in a silence around some huge issues that, like my own writing, also gestured towards unnamed pain. I sensed my mother withholding the why underneath the why. Just like old times. Her answers often trailed into silences from which, nag as I might, I could never persuade her to utter one more syllable. If each of those moments had been my mother writing about an aspect of her life and I was her writing teacher, I too would have told her to look at the things that you purposely leave out, or deal with but only glancingly.

This double push of my mother’s pseudo-reason and my mentor calling me out propelled me into removing my muzzle, one draft at a time. Over the next five years, I began allowing myself to express through Dessie’s story how I really felt about the most trumpeted and celebrated aspects of Ethiopian history and culture—the easy stuff: resistance to colonization, an ancient brand of Christianity, a unique written script, even the coffee ceremony and the iconic Ethiopian Airlines—contrasted against the most suppressed. I worked my way in from the edges, so to speak. Until, finally, I hit the hot center, what my mentor had sensed as a persistent returning sting and ache: the double robbery that is childhood sexual abuse, and the silence about it in the habesha community.

Incrementally, I also began disclosing that I am a survivor to people in my innermost circle of chosen and blood family. And what do you know, the world did not split open! At least not in the way I had initially imagined. Perhaps because of my own predisposition to doom and gloom, I had interpreted Rukeyser’s line the world would split open as a disaster scenario. But now I realize how flexible that line is.

The world could split open like a flower in bloom, like a woman shattering the glass that had separated her from true connection. Like the global event that became multitudes of habesha women finally telling their stories online, which resulted in the creation of #metooethiopia, adding its support to the Yellow Movement and Setaweet, pre-existing, homegrown feminist groups in Ethiopia.

All that, just from several hundred habesha women telling their stories anonymously. I wonder what would happen if they, and others, shed their anonymity. Is that not the final, hardest step towards fully regaining one’s voice? If they felt that they could share their stories as openly as survivors of any other kind of life-threatening event. Exactly whose world would split open then? Who should really be afraid?

__________________________________

Rebecca Fisseha’s debut novel, Daughters of Silence, is out now from Goose Lane Editions.